Fact #61398

When:

Short story:

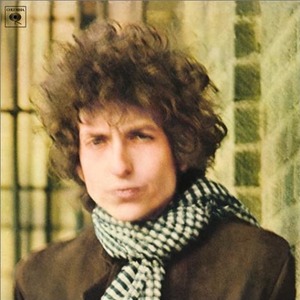

Bob Dylan releases rock music's first double-album, Blonde On Blonde, on Columbia Records in the USA.

Bob Dylan releases rock music's first double-album, Blonde On Blonde, on Columbia Records in the USA.Full article:

VINYL ICON – BLONDE ON BLONDE

By Johnny Black

Hi Fi News - January 2010

Nashville, Tennessee, lies 750 miles south west of Bob Dylan's first stomping ground, New York City. It’s just a two-hour plane ride but, when Dylan flew down in February 1966 to record what would become his masterpiece, Blonde On Blonde, the two cities were worlds apart.

"Anybody you ask will say that Nashville began when Dylan came down here. That’s the way I feel about it, too," states Bob Johnston, who produced not just six Bob Dylan albums but also classics by Simon & Garfunkel, Leonard Cohen, Johnny Cash and too many more to mention. "Nashville was a different place before that. The producers and record people ran the business with an iron fist. They did what they wanted to, and the artist was at their beck and call." Dylan and Johnston turned that relationship on its head.

“We didn’t know who Bob Dylan was,” admits guitarist Wayne Moss, one of the hot Nashville sessioneers whose astonishing instrumental dexterity elevated Blonde On Blonde from what everybody was hoping for - Dylan’s best album yet - into one of the greatest albums in the entire rock canon. Indeed, many critics now feel that the recordings Dylan and Johnston made together produced the very first albums that could be described with just that one word – rock.

Originally, in the early 60s, Dylan had been hailed as the saviour of folk music, but then The Byrds gave him his first American No1 single in June 1965 with their jangling cover of his song Mr Tambourine Man, which turned him on to the potential of the folk-rock blend.

The Dylan/Johnston collaboration meshed perfectly on Dylan's first completely electric album Highway 61 Revisited. However, when they re-convened in Columbia Studio A in New York City on November 30, 1965, the magic seemed to have dissipated. Fourteen takes of Dylan's lengthy opus Visions Of Johanna were laid down but none were deemed usable.

A successful take of the sardonic One Of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later) was recorded on the 25th, but the next four sessions were all either cancelled or unfruitful.

Johnston, however, wasn't ready to throw in the towel. "I had recorded quite a few sessions in Nashville,” he points out, “and I knew that the players I used down there would be great for cutting Dylan’s songs.” Dylan was initially sceptical, but on February 14 the first session began in Columbia’s Nashville studio on Music Row.

Dylan’s favoured organist, Al Kooper, was then touring with his band The Blues Project, so he flew down from Columbus, Ohio. “Bob had both me and Robbie Robertson (of The Band) on those sessions, to increase his comfort zone,” explains Kooper, "because we had both worked with him in New York.” Two additional guitarists, Jerry Kennedy and Joe South, converged on Nashville from Miami and Atlanta respectively.

The core of the studio musicians, however, were all local Nashville hotshots. “Bob Johnston had used us on many sessions before Dylan,” explains Wayne Moss. “Charlie McCoy played bass and trumpet and was the leader of the band. We had Kenneth Buttrey, the world’s greatest drummer, and Hargus Robbins, the blind piano player.”

Although Robbie Robertson had worked with Dylan before, he felt a need to prove himself to the Nashville elite. “It was very clique-ish. The musicians that played on sessions there didn’t like outsiders coming in … it was kind of like, ‘What do we need him for?’”

It wasn’t until he contributed the impressive bluesy licks on Obviously 5 Believers that he felt he had won them over. “I was doing something that none of them did, so I don’t think they felt I was treading on their territory.”

Kooper too felt intimidated by just how far ahead of him the Nashville sessioneers were as players. “In I Want You, for instance, I had the opening guitar lick in my head and Wayne Moss came up with that amazing sixteenth note run that comes out of it later. I almost fell off the chair when he did that. Nobody in New York could have done that, or even have thought of doing that.”

Equally, of course, it’s unlikely that anybody in Nashville would ever have come up with the strategy Dylan advanced for the recording of Rainy Day Women Nos 12 & 35 – to get the band as drunk as possible before starting.

Henry Strzelecki, appointed to play bass, became so pie-eyed he couldn’t stand up. “Or even sit up,” notes Moss. It was all he could do to lie on the floor and play the bass pedals on the organ with his hands, while Moss took over on bass guitar.

Unsurprisingly, the playing on Rainy Day Women leaves something to be desired, but Dylan undeniably achieved his aim of creating the atmosphere of a crazed party, with music supplied by a Salvation Army band.

Nor was this the only time Dylan’s working methods proved completely alien to the Nashvillians. “We’d never worked with anybody who didn’t have all their songs written before they came to the studio,” points out Moss, who was stunned when Dylan cut short a session for Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands just minutes after it began, to work on the lyric. “He told us to take a break at about two thirty, and didn’t call us back until about three am the next morning.”

“Everybody else went down, played ping pong, got something to eat, went to sleep," remembers Johnston, "until Dylan came out and said, ‘Hey, I got that song finished. Is anybody around?’ I went and got everybody up. Dylan says, ‘Well, it goes like this … G, C, B, dah de dah de dah … and he walked away. And all these guys, they didn’t know what to do. I said, ‘Play. Don’t stop. Just keep playin’.”

Eleven minutes later, it was done. “We played it back and nobody could believe it, because they knew that their lives had changed, Nashville had changed and music had changed.”

It's widely agreed that Dylan's wife at the time, Sara Lownds, was his muse for the epic Sad Eyed Lady. The jury remains out, however, on the inspiration for the album’s next-longest song, Visions Of Johanna, although Dylan's mentor, friend and sometime lover, Joan Baez, is the likeliest candidate.

Just Like A Woman’s subject is usually assumed to be former Boston debutante turned Andy Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, with whom Dylan had enjoyed a brief friendship.

One song that evidently existed for some while before Dylan went to Nashville was 4th Time Around. Learning that Dylan had played it to The Beatles, Al Kooper, who knew Dylan had played it to the Beatles, told me that he asked, "if they’d remarked on how similar it sounded to Norwegian Wood, and he said, ‘When I played it to them, there was no Norwegian Wood.’”'

Whether it was Bob Johnston, Nashville, the musicians, or some inexplicable combination of all three, Dylan was spurred into an astonishingly prolific burst of creativity because Blonde On Blonde turned out to be not just a great album, but a great double album. As Dylan himself later acknowledged, “At the time of Blonde On Blonde, I was going at a tremendous speed.”

Rock’s first double album hit the streets on 16 May 1966 (believe it or not, the same day as The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds) and, although it never rose above 9 in America and narrowly missed the top slot over here, the ripples began spreading immediately. Wordsmiths around the world used Blonde On Blonde as the spur for their own lyrical flights of fancy; the shift from a market dominated by singles to one dominated by albums was now inevitable, and Dylan’s union of rock and country would lead to artists beginning to break down the stylistic divisions that had kept them locked down for so long.

“To me, Dylan was one of that tiny handful of men that you could truly call a prophet," says Bob Johnston all these years later. "He wasn’t just changing music, he was changing attitudes, changing our society. And I was able to help him.”

-------------------------------------------------

VINYL ICON – BLONDE ON BLONDE

PRODUCTION NOTES

by Johnny Black

When producer Bob Johnston first moved down to Columbia's Nashville studios, some years before Blonde On Blonde, he pulled out all of the small sound booths which had been installed to minimise sound leakage. He wanted, he says, to create a space where the players could see each other and function in more organic way.

Session guitarist Wayne Moss points out, however, that even though the Nashville studio thus became virtually an identical replica of Columbia’s New York facility, the sound was nowhere near as good during the Blonde On Blonde sessions because of, you guessed it, leakage. “Charlie McCoy’s bass was leaking into Dylan’s voice and guitar mikes,” he recalls, “so he had to run his bass directly into the desk and monitor what he was playing on headphones. We couldn’t hear any bass in the room at all.”

Bob Johnston's main concern, however, was to get a good recording of Dylan. "I always used three microphones on Dylan," he says, "'cause his head spun around so much. I used a big [Neumann] U47 on him, same as I used on Johnny Cash later. I would put a baffle over the top of his guitar because he played while he sang lead vocals. I didn't use any EQ on the band, just set the mics up right to make each instrument sound the best it could. I used some EQ on Dylan's voice."

Although nominally a keyboardist, Al Kooper (who subsequently founded Blood, Sweat & Tears) describes his primary function during the Blonde On Blonde sessions as being Dylan’s music director. “I asked him if I could go to the studio an hour before him and teach the songs to the band, so that when Bob got there we would be ready to go and he wouldn’t have to wait around while arrangements were made up. I would teach the band the arrangements that I had in my head for these songs and, of course, they would get them instantly.”

---------------------------------------------------------------

ADDITIONAL QUOTE...

Keith Richards (guitarist, Rolling Stones) : He showed you that rock 'n' roll didn't need to be quite so restricted by that verse-chorus-verse formula,' he explained to NME. 'We all pushed each other on in those days. Bob's a nasty little b****r. I remember him saying to me, 'I could have written... Satisfaction, Keith, but you couldn't have written Desolation Row.' I said, 'Well, you're right there Bob!''

Tweet this Fact

By Johnny Black

Hi Fi News - January 2010

Nashville, Tennessee, lies 750 miles south west of Bob Dylan's first stomping ground, New York City. It’s just a two-hour plane ride but, when Dylan flew down in February 1966 to record what would become his masterpiece, Blonde On Blonde, the two cities were worlds apart.

"Anybody you ask will say that Nashville began when Dylan came down here. That’s the way I feel about it, too," states Bob Johnston, who produced not just six Bob Dylan albums but also classics by Simon & Garfunkel, Leonard Cohen, Johnny Cash and too many more to mention. "Nashville was a different place before that. The producers and record people ran the business with an iron fist. They did what they wanted to, and the artist was at their beck and call." Dylan and Johnston turned that relationship on its head.

“We didn’t know who Bob Dylan was,” admits guitarist Wayne Moss, one of the hot Nashville sessioneers whose astonishing instrumental dexterity elevated Blonde On Blonde from what everybody was hoping for - Dylan’s best album yet - into one of the greatest albums in the entire rock canon. Indeed, many critics now feel that the recordings Dylan and Johnston made together produced the very first albums that could be described with just that one word – rock.

Originally, in the early 60s, Dylan had been hailed as the saviour of folk music, but then The Byrds gave him his first American No1 single in June 1965 with their jangling cover of his song Mr Tambourine Man, which turned him on to the potential of the folk-rock blend.

The Dylan/Johnston collaboration meshed perfectly on Dylan's first completely electric album Highway 61 Revisited. However, when they re-convened in Columbia Studio A in New York City on November 30, 1965, the magic seemed to have dissipated. Fourteen takes of Dylan's lengthy opus Visions Of Johanna were laid down but none were deemed usable.

A successful take of the sardonic One Of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later) was recorded on the 25th, but the next four sessions were all either cancelled or unfruitful.

Johnston, however, wasn't ready to throw in the towel. "I had recorded quite a few sessions in Nashville,” he points out, “and I knew that the players I used down there would be great for cutting Dylan’s songs.” Dylan was initially sceptical, but on February 14 the first session began in Columbia’s Nashville studio on Music Row.

Dylan’s favoured organist, Al Kooper, was then touring with his band The Blues Project, so he flew down from Columbus, Ohio. “Bob had both me and Robbie Robertson (of The Band) on those sessions, to increase his comfort zone,” explains Kooper, "because we had both worked with him in New York.” Two additional guitarists, Jerry Kennedy and Joe South, converged on Nashville from Miami and Atlanta respectively.

The core of the studio musicians, however, were all local Nashville hotshots. “Bob Johnston had used us on many sessions before Dylan,” explains Wayne Moss. “Charlie McCoy played bass and trumpet and was the leader of the band. We had Kenneth Buttrey, the world’s greatest drummer, and Hargus Robbins, the blind piano player.”

Although Robbie Robertson had worked with Dylan before, he felt a need to prove himself to the Nashville elite. “It was very clique-ish. The musicians that played on sessions there didn’t like outsiders coming in … it was kind of like, ‘What do we need him for?’”

It wasn’t until he contributed the impressive bluesy licks on Obviously 5 Believers that he felt he had won them over. “I was doing something that none of them did, so I don’t think they felt I was treading on their territory.”

Kooper too felt intimidated by just how far ahead of him the Nashville sessioneers were as players. “In I Want You, for instance, I had the opening guitar lick in my head and Wayne Moss came up with that amazing sixteenth note run that comes out of it later. I almost fell off the chair when he did that. Nobody in New York could have done that, or even have thought of doing that.”

Equally, of course, it’s unlikely that anybody in Nashville would ever have come up with the strategy Dylan advanced for the recording of Rainy Day Women Nos 12 & 35 – to get the band as drunk as possible before starting.

Henry Strzelecki, appointed to play bass, became so pie-eyed he couldn’t stand up. “Or even sit up,” notes Moss. It was all he could do to lie on the floor and play the bass pedals on the organ with his hands, while Moss took over on bass guitar.

Unsurprisingly, the playing on Rainy Day Women leaves something to be desired, but Dylan undeniably achieved his aim of creating the atmosphere of a crazed party, with music supplied by a Salvation Army band.

Nor was this the only time Dylan’s working methods proved completely alien to the Nashvillians. “We’d never worked with anybody who didn’t have all their songs written before they came to the studio,” points out Moss, who was stunned when Dylan cut short a session for Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands just minutes after it began, to work on the lyric. “He told us to take a break at about two thirty, and didn’t call us back until about three am the next morning.”

“Everybody else went down, played ping pong, got something to eat, went to sleep," remembers Johnston, "until Dylan came out and said, ‘Hey, I got that song finished. Is anybody around?’ I went and got everybody up. Dylan says, ‘Well, it goes like this … G, C, B, dah de dah de dah … and he walked away. And all these guys, they didn’t know what to do. I said, ‘Play. Don’t stop. Just keep playin’.”

Eleven minutes later, it was done. “We played it back and nobody could believe it, because they knew that their lives had changed, Nashville had changed and music had changed.”

It's widely agreed that Dylan's wife at the time, Sara Lownds, was his muse for the epic Sad Eyed Lady. The jury remains out, however, on the inspiration for the album’s next-longest song, Visions Of Johanna, although Dylan's mentor, friend and sometime lover, Joan Baez, is the likeliest candidate.

Just Like A Woman’s subject is usually assumed to be former Boston debutante turned Andy Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, with whom Dylan had enjoyed a brief friendship.

One song that evidently existed for some while before Dylan went to Nashville was 4th Time Around. Learning that Dylan had played it to The Beatles, Al Kooper, who knew Dylan had played it to the Beatles, told me that he asked, "if they’d remarked on how similar it sounded to Norwegian Wood, and he said, ‘When I played it to them, there was no Norwegian Wood.’”'

Whether it was Bob Johnston, Nashville, the musicians, or some inexplicable combination of all three, Dylan was spurred into an astonishingly prolific burst of creativity because Blonde On Blonde turned out to be not just a great album, but a great double album. As Dylan himself later acknowledged, “At the time of Blonde On Blonde, I was going at a tremendous speed.”

Rock’s first double album hit the streets on 16 May 1966 (believe it or not, the same day as The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds) and, although it never rose above 9 in America and narrowly missed the top slot over here, the ripples began spreading immediately. Wordsmiths around the world used Blonde On Blonde as the spur for their own lyrical flights of fancy; the shift from a market dominated by singles to one dominated by albums was now inevitable, and Dylan’s union of rock and country would lead to artists beginning to break down the stylistic divisions that had kept them locked down for so long.

“To me, Dylan was one of that tiny handful of men that you could truly call a prophet," says Bob Johnston all these years later. "He wasn’t just changing music, he was changing attitudes, changing our society. And I was able to help him.”

-------------------------------------------------

VINYL ICON – BLONDE ON BLONDE

PRODUCTION NOTES

by Johnny Black

When producer Bob Johnston first moved down to Columbia's Nashville studios, some years before Blonde On Blonde, he pulled out all of the small sound booths which had been installed to minimise sound leakage. He wanted, he says, to create a space where the players could see each other and function in more organic way.

Session guitarist Wayne Moss points out, however, that even though the Nashville studio thus became virtually an identical replica of Columbia’s New York facility, the sound was nowhere near as good during the Blonde On Blonde sessions because of, you guessed it, leakage. “Charlie McCoy’s bass was leaking into Dylan’s voice and guitar mikes,” he recalls, “so he had to run his bass directly into the desk and monitor what he was playing on headphones. We couldn’t hear any bass in the room at all.”

Bob Johnston's main concern, however, was to get a good recording of Dylan. "I always used three microphones on Dylan," he says, "'cause his head spun around so much. I used a big [Neumann] U47 on him, same as I used on Johnny Cash later. I would put a baffle over the top of his guitar because he played while he sang lead vocals. I didn't use any EQ on the band, just set the mics up right to make each instrument sound the best it could. I used some EQ on Dylan's voice."

Although nominally a keyboardist, Al Kooper (who subsequently founded Blood, Sweat & Tears) describes his primary function during the Blonde On Blonde sessions as being Dylan’s music director. “I asked him if I could go to the studio an hour before him and teach the songs to the band, so that when Bob got there we would be ready to go and he wouldn’t have to wait around while arrangements were made up. I would teach the band the arrangements that I had in my head for these songs and, of course, they would get them instantly.”

---------------------------------------------------------------

ADDITIONAL QUOTE...

Keith Richards (guitarist, Rolling Stones) : He showed you that rock 'n' roll didn't need to be quite so restricted by that verse-chorus-verse formula,' he explained to NME. 'We all pushed each other on in those days. Bob's a nasty little b****r. I remember him saying to me, 'I could have written... Satisfaction, Keith, but you couldn't have written Desolation Row.' I said, 'Well, you're right there Bob!''