Fact #187649

When:

Short story:

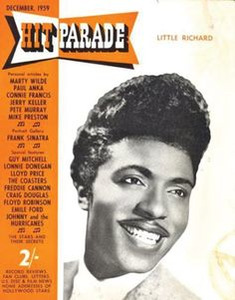

In Cosimo Matassa's J And M Studios, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Little Richard begins his first two day recording session for Specialty Records.

In Cosimo Matassa's J And M Studios, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Little Richard begins his first two day recording session for Specialty Records.Full article:

Jerry Wexler (Billboard journalist) : I met everybody in the business. music publishers, song pluggers, producers, label owners. All sorts of characters. Those were the days of the crazy barons like Nathan, Herman Lubinsky (of Savoy), Lew Chudd (of Imperial) and Art Rupe (of Specialty).

I saw Little Richard's Specialty contract one time, and it specified that the more records he sold, the smaller a royalty he got.

Art Rupe (owner, Specialty Records) : We received his tape about seven or eight months before we recorded. Richard kept bugging us on the phone, "Are you going to record me? When are you going to record me?" Every fourth or fifth day we'd get a phone call from him. One time from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, another time from Atlanta, then from Jacksonville. I'd never seen Richard, and neither had Bumps Blackwell - this was all by mail and phone.

Little Richard : Ten months after I'd sent them my tape, Specialty sent for me. We had been playing in Fayetteville, Tennessee, USA. I got the call early in the morning, 'Meet us in New Orleans.' I slipped away and left my band in the motel, except for Henry Nash, Lee Diamond, and Chuck Connors.

Art Rupe : When we were ready to record, we found out that he was still under contract to Peacock. So he made a deal to buy his contract back for six hundred dollars, and we loaned him the money and then signed him.

Art Rupe (owner, Specialty Records) : Richard had told me he liked Fats Domino's sound, and I thought maybe lightning would strike twice if we recorded Richard at J and M Studios in New Orleans, like we did Lloyd Price. We even planned to do eight sides instead of four.

Bumps Blackwell : When I got to New Orleans, Cosimo Matassa, the studio owner, called and said, "Hey, man, this boy's down here waiting for you.' When I walked in, there's this cat in this loud shirt, with hair waved up six inches above his head. He was talking wild, thinking up stuff just to be different, you know ? I could tell he was a mega- personality. So we got to the studio, on Rampart and Dumaine. I had the studio band in - Lee Allen on tenor sax, Alvin "Red" Tyler on baritone sax, Earl Palmer on drums, Edgar Blanchard and Justin Adams on guitar, Huey "Piano" Smith and James Booker on piano, Frank Fields, bass, all of them the best in New Orleans. They were Fats Domino's session men.

Let me tell you about the recording methods we used in those days. Recording technicians of today, surrounded by huge banks of computer-controlled sound technology, would find the engineering techniques available in the 1950s as primitive as the Kitty Hawk is to the space shuttle. When I started there was no tape. It was disk to disk. There was no such thing as overdubbing. Those things we did at Cosimo's were on tape, but they were all done straight ahead. The tracks you heard were the tracks as they were recorded from beginnIng to end.

We would take sixty or seventy takes. We were recording two tracks. Maybe we might go to surgery and intercut a track, or cut a track at the end or something, but we didn't know what overdubbing was.

The studio was just a back room in a furniture store, like an ordinary motel room. For the whole orchestra. There'd be a grand piano just as you came in the door. I'd have the grand's lid up with a mike in the keys and Alvin Tyler and Lee Allen would be blowing into that. Earl Palmer's drums were out of the door, where I had one mike as well. The bassman would be way over the other side of the studio. You see, the bass would cut and bleed in, so I could get the bass.

The recording equipment was a little old quarter-inch, single-channel Ampex Model 300 in the next room. I would go in there and listen with earphones. If it didn't sound right, I'd just keep moving the mikes around. I would have to set up all those things. But, you see, once I had got my sound, my room sound, well then I would just start running my numbers straight down.

It might take me forty-five minutes, an hour, to get that balance within the room, but once those guys hit a groove, you could go on all night. When we got it, we got it. I would lIke to see some of these great producers today produce on monaural or binaural equipment with the same atmosphere. Cos the problem is, if you're going to get a room sound with the timbre of the instruments, you can't put them together as a band and just start playing. All of a sudden one horn's going to stick out.

So I had to place the mikes very carefully and put the drummer outside the door.

Well, the first session was to run six hours, and we planned to cut eight sides. Richard ran through the songs on his audition tape. He's My Star was very disappointing. I did not even record it. But Wonderin' we got in two takes. Then we got I'm Just a Lonely Guy which was written by a local girl called Dorothy La Bostrie, who was always pestering me to record her stuff. Then The Most I Can Offer, and then Baby.

So far so good. But it wasn't really what I was looking for. I had heard that Richard's stage act was really wild but, in the studio that day, he was very inhibited. Possibly his ego was pushing him to show his spiritual feeling or something, but it certainly wasn't coming together like I had expected and hoped.

The problem was that what he looked like, and what he sounded like didn't come together. If you look like Tarzan and sound like Mickey Mouse it just doesn't work out. So I'm thinking, Oh, Jesus... You know what it's like when you don't know what to do? It's "Let's take a break. Let's go to lunch." I had to think. I didn't know what to do. I couldn't go back to Rupe with the material I had because there was nothing there that I could put out. Nothing that I could ask anyone to put a promotion on. Nothing to merchandise. And I was paying out serious money.

(Source : not known)

Tweet this Fact

I saw Little Richard's Specialty contract one time, and it specified that the more records he sold, the smaller a royalty he got.

Art Rupe (owner, Specialty Records) : We received his tape about seven or eight months before we recorded. Richard kept bugging us on the phone, "Are you going to record me? When are you going to record me?" Every fourth or fifth day we'd get a phone call from him. One time from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, another time from Atlanta, then from Jacksonville. I'd never seen Richard, and neither had Bumps Blackwell - this was all by mail and phone.

Little Richard : Ten months after I'd sent them my tape, Specialty sent for me. We had been playing in Fayetteville, Tennessee, USA. I got the call early in the morning, 'Meet us in New Orleans.' I slipped away and left my band in the motel, except for Henry Nash, Lee Diamond, and Chuck Connors.

Art Rupe : When we were ready to record, we found out that he was still under contract to Peacock. So he made a deal to buy his contract back for six hundred dollars, and we loaned him the money and then signed him.

Art Rupe (owner, Specialty Records) : Richard had told me he liked Fats Domino's sound, and I thought maybe lightning would strike twice if we recorded Richard at J and M Studios in New Orleans, like we did Lloyd Price. We even planned to do eight sides instead of four.

Bumps Blackwell : When I got to New Orleans, Cosimo Matassa, the studio owner, called and said, "Hey, man, this boy's down here waiting for you.' When I walked in, there's this cat in this loud shirt, with hair waved up six inches above his head. He was talking wild, thinking up stuff just to be different, you know ? I could tell he was a mega- personality. So we got to the studio, on Rampart and Dumaine. I had the studio band in - Lee Allen on tenor sax, Alvin "Red" Tyler on baritone sax, Earl Palmer on drums, Edgar Blanchard and Justin Adams on guitar, Huey "Piano" Smith and James Booker on piano, Frank Fields, bass, all of them the best in New Orleans. They were Fats Domino's session men.

Let me tell you about the recording methods we used in those days. Recording technicians of today, surrounded by huge banks of computer-controlled sound technology, would find the engineering techniques available in the 1950s as primitive as the Kitty Hawk is to the space shuttle. When I started there was no tape. It was disk to disk. There was no such thing as overdubbing. Those things we did at Cosimo's were on tape, but they were all done straight ahead. The tracks you heard were the tracks as they were recorded from beginnIng to end.

We would take sixty or seventy takes. We were recording two tracks. Maybe we might go to surgery and intercut a track, or cut a track at the end or something, but we didn't know what overdubbing was.

The studio was just a back room in a furniture store, like an ordinary motel room. For the whole orchestra. There'd be a grand piano just as you came in the door. I'd have the grand's lid up with a mike in the keys and Alvin Tyler and Lee Allen would be blowing into that. Earl Palmer's drums were out of the door, where I had one mike as well. The bassman would be way over the other side of the studio. You see, the bass would cut and bleed in, so I could get the bass.

The recording equipment was a little old quarter-inch, single-channel Ampex Model 300 in the next room. I would go in there and listen with earphones. If it didn't sound right, I'd just keep moving the mikes around. I would have to set up all those things. But, you see, once I had got my sound, my room sound, well then I would just start running my numbers straight down.

It might take me forty-five minutes, an hour, to get that balance within the room, but once those guys hit a groove, you could go on all night. When we got it, we got it. I would lIke to see some of these great producers today produce on monaural or binaural equipment with the same atmosphere. Cos the problem is, if you're going to get a room sound with the timbre of the instruments, you can't put them together as a band and just start playing. All of a sudden one horn's going to stick out.

So I had to place the mikes very carefully and put the drummer outside the door.

Well, the first session was to run six hours, and we planned to cut eight sides. Richard ran through the songs on his audition tape. He's My Star was very disappointing. I did not even record it. But Wonderin' we got in two takes. Then we got I'm Just a Lonely Guy which was written by a local girl called Dorothy La Bostrie, who was always pestering me to record her stuff. Then The Most I Can Offer, and then Baby.

So far so good. But it wasn't really what I was looking for. I had heard that Richard's stage act was really wild but, in the studio that day, he was very inhibited. Possibly his ego was pushing him to show his spiritual feeling or something, but it certainly wasn't coming together like I had expected and hoped.

The problem was that what he looked like, and what he sounded like didn't come together. If you look like Tarzan and sound like Mickey Mouse it just doesn't work out. So I'm thinking, Oh, Jesus... You know what it's like when you don't know what to do? It's "Let's take a break. Let's go to lunch." I had to think. I didn't know what to do. I couldn't go back to Rupe with the material I had because there was nothing there that I could put out. Nothing that I could ask anyone to put a promotion on. Nothing to merchandise. And I was paying out serious money.

(Source : not known)