Fact #170915

When:

Short story:

Full article:

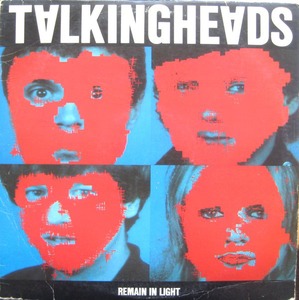

Things did not look good when Talking Heads assembled in The Bahamas to start recording their fourth album, Remain In Light. According to Bassist Tina Weymouth, long-time Heads producer Brian Eno was reluctant to become involved again, having fallen out with David Byrne during recording of their collaborative album, My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. Within a week, engineer Rhett Davies quit in frustration, and Byrne has confirmed that there was tension between himself and Weymouth over the direction of the music.

He has said, for example, that, “We were really intrigued and excited by the formal aspects of Afican music.” She, however, insisted, “No-one discussed with us the fact that we were going to be playing in an African style.”

Nevertheless, what they created was a whole new direction, not just for Talking Heads but for 80s rock in general. With the quartet expanded by the addition of horns, extra percussion and voices, they moved away from traditional songwriting by improvising songs in the studio, diving headlong into the complexities of African polyrhythms and replacing Byrne’s urban paranoia with much more affirmative lyrics.

“I think the music was important in that,” says Byrne. “The anxiety of my lyrics and my singing didn’t seem appropriate to this kind of music. This music is more positive, though a little mysterious at the same time.”

The other vital ingredient was Eno, taking a much more active part in the music here than on previous Talking Heads albums. Eno’s fingerprints are everywhere, from vocal harmonies and counterpoints to layered ambient sounds, lyrics and rhythmic devices. Guitarist Chris Frantz confirms that “The barriers between musician and producer were being broken down ‘cause we were writing the songs in the studio.”

“An album of brave inventions and haunting textures,” drooled NME on release, but Rolling Stone nailed it even better with “Scary, funny music to which you can dance and think, think and dance, dance and think, ad infinitum.”

Predictably, though, the world wasn’t ready for doing two things at once. “It was the worst-selling Talking Heads album ever,” points out Frantz. Tightly formatted American radio found it impossible to programme because, as Byrne recalls, “The reaction we heard was that it sounded too black for white radio and too white for black radio.”

By the end of the 80s, however, Remain In Light featured at No4 in Rolling Stone’s selection of the decade’s greatest albums, and it continues to attract new converts to its irresistably quirky stew of traditional and avant-garde elements.

REMAIN IN LIGHT : THE ORAL HISTORY

Brian Eno (producer) : I was initially reluctant to produce Remain In Light. I had been working for some months with David on My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, and my mind was still very much in that record. I agreed to work with the band on generating some new material, but I suggested they find another producer.

Tina Weymouth (Talking Heads) : Brian hadn’t even stayed to finish Bush Of Ghosts. Something happened between him and David. We asked him to work on Remain In Light and at first he was reluctant. I really don’t know what went down between them.

Jerry Harrison (Talking Heads) : Remain In Light was almost like recording rehearsals. You might say it was started with a concept, part one of which was tobe able to capture (and sometimes keep) mistakes that happen right when you start something. Part two was to create sections by building up parts and polyrhythms. Sometimes you can get too caught up in doing arrangements, and this was a way of opening up.

Tina Weymouth : When we were making Speaking in Tongues and Remain in Light we were jamming and from that we were taking the best bits and then recording those and then improvising on top of those, the vocals and the melody, the lyric and all that.

Brian Eno : After a few days of playing together, the band, and in particular Chris and Tina, requested very forcefully that I reconsider producing the record. I said that I would do it willingly, on condition that they accepted that I would treat it as I treated my own work - that’s to say as a continuation of the ideas I’d been involved with on My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts.

I explained as carefully as I could that this would not be a production in the usual sense, that I was only interested in pushing certain musical ideas at the moment and that, if I were producing their record, I would pursue those ideas there. I believe I could not have been more clear about this.

The band understood and accepted what I said. They replied that the ideas I had outlined were not, anyway unfamiliar to them. This was indeed true - they were extensions of what we’d already done on previous records - and that they were in sympathy with the idea of pursuing a rather exclusive objective such as I’d described. They also urged me totreat the album as a collaboration rather than as a simple production, and it was on this basis we proceeded.

David Byrne : I think she (Tina) was understandably upset that Brian and I were pushing this whole direction so adamantly. It was almost like it was a train out of control or something. Maybe she felt she wasn’t a part of that. She was a part of it, but I can understand how she might have felt.

Brian Eno : I wouldn't call myself the fifth Head or any other number Head.

Jerry Harrison : We deliberately switched instruments, because sometimes people can come up with a naïve part that somebody else might not come up with. On some things, I started out playing drums, with Chris playing synthesiser, and later we switched back. That works quite well as a way of getting away from the things you fall into, in addition to being fun.

David Byrne : It’s essential that, when you listen to it, it has some effect on your body - whether you stand up and dance to it or not. It’s up to you. When we were working in the studio that was always my criterion for judging a part - whether it did something to the piece that makes you want to move your body in a more interesting way. You can use your body as much as a judge of the various parts as you do your ears.

Chris Frantz : Remain In Light was a difficult album to make. We wanted to do something ground-breaking, but we didn’t want to get into fights about it. And a couple of times, we did get into fights - musical fights - because somebody wanted to go one way and another person thought it shouldn’t sound like that.

David Byrne (Talking Heads) : We wanted to develop an understanding of the African musical concept of interlocking, interdependent parts and rhythms that combine to make a coherent whole. It’s completely different from playing rock songs; it’s not just a band executing a tune.

Tina Weymouth : David had such a completely different theory about it. His theory was far more intellectual and bookish. I never felt that there was any conscious, manipulative effort on our part to play African styles. To me and Chris, it seemed as if that importance was attached to the record after the fact. They (Byrne and Eno) were very keen on some literature they’d been reading…

David Byrne : There was actually only one that I was reading during the making of the record. And I felt that had had something to do with what we were doing.

The only one that had directly to do with music was the one called African Rhythms And African Sensibility by this fellow, John Miller Chernoff. Then there was African Art And Motion, which is about how the art works with the dancing and the rituals. That’s by Robert Farris Thompson.the other one was The Divine Horseman, a book about voodoo in Haiti, by this woman, Maya Dering, who used to be a film-maker and who, in later years, got wrapped up in voodoo.

Those books helped me put together ideas that I was already having about the way music expresses the culture it comes from. That seems like a real obvious idea, it’s nothing new. But it somehow became clearer to me, I had a lot clearer idea of how it works. That was exciting for me because, as we were doing bits of music or recording things, I could hear a lot of implications in different musical parts - social implications and political implications and whatnot.

Tina Weymouth : I suppose we were all quite aware of African music sometime before that. But no-one discussed with us the fact we were going to be playing in an African style. To us, it was all very funny, putting this bibliography together with a record. It’s so pseudo-intellectual, and everything we were trying to get away from.

David Byrne : I just thought they were good books,and at least one of them had a lot of influence on me. So I just thought I’d pass along that information.

David Byrne : Born Under Punches, that was real spontaneous, just improvised in the studio, spontaneous emissions.

Tina Weymouth : It was the beginning of David finding a way to improvise very quickly in the studio. Before, it had been a very private kind of struggle.

David Byrne : Eno gave me confidence in the studio. He encouraged me to go in with nothing prepared.

I feel less afraid of many things now, feel more confident. And I think the music was important in that. It demanded a completely different attitude. The anxiety of my lyrics and my singing didn’t seem appropriate to this kind of music. This music is more positive, though a little mysterious at the same time. So it was important that I wrote lyrics that also had these qualities.

David Byrne : We (Byrne and Eno) both grew up listening to music that had its roots in Africa. The African music we listen to isn't that different - in spirit, anyway - than a lot of rhythm and blues, or funk, that we're quite accustomed to and that most of Talking Heads' music is based on. It's not that big a leap."

Brian Eno (producer) : It has melodies you can understand, rhythms you can understand. The other thing about Africa is that both of us, and many other people in the world, are interested in discovering whether there are other moral philosophies - not a word one bandies lightly in the contemporary rock press, I must say.

The way I see it, during the '50s and '60s people were very impressed by Eastern philosophies because they seemed to represent another option about how you could think about or organize things, your life being one of them. They also had an important musical connection; there was a whole group of composers, both rock and 'serious,' who were very influenced by Eastern ideas. It's become a rather unpleasant part of the currency of '70s thinking.

We were both attracted to the African thing initially for music reasons. We began reading about African music at first but you can't read about African music without finding out about African society because they're so closely interwoven. Music stands as a crystallization of cultural standards.

Nona Hendryx (vocalist, Remain In Light) : I think David really liked African rhythms and music. It’s something he was instinctively drawn to.It was a risk, getting into African rhythms and sounds and being a white person, expressing it as something coming from him.

David Byrne : There's a very different kind of spirituality in Africa than what we grew up with. As opposed to our "sober, very serious" approach, in Africa and a lot of other cultures, probably most of the cultures in the world, things that are considered spiritual - performances, music - are also exciting and fun. People have a good time; it's not sacred in the sense that you can't talk while a performance is going on, or have a drink or smoke a cigarette. There isn't that separation of pleasure and spiritual things.

Brian Eno : All the Talking Heads and myself have been listening to African records. You can't steer anyone in a direction they're not already going in; there has to be momentum or it isn't going to succeed. David and I did articulate a way of working - we said, 'This is the way we want to work,' rather than all other possible ways - but it wasn't an idea that was foreign to everyone, Nobody said, 'God, what's this?' "

David Byrne : It was more a case of everyone going, 'Oh yeah, exactly.” I think it was something that everyone in the band was interested in to some degree, but Brian and myself were more actively involved in reading books and listening to records.

Brian Eno : We weren't trying to do African music. We were trying to use some of the things we thought we'd learn from that in making a newer version of our own music. I don't think it's like putting on a new set of clothes and 'here we are, it 's all new.' It's saying, 'This might be a clearer version of what we've been trying to do anyway' - or a more refined version.

David Byrne : I saw more and more similarities between African music and black American music. I thought yes, it's discontent with a lot of white music and a lot of the sensibility that white music is about, but [African music] is not as exotic as it initially sounds.

Brian Eno : Also, it's not so much that you go to another culture to discover

some thing entirely new; it's to discover a different emphasis on things. I

think we were interested in finding some way to emphasize different aspects,

not suddenly to present us with a whole lot of new ones. Most of the things we ran into as we were reading and listening were not totally exotic but a different balance - a balance that seemed quite attractive to us.

David Byrne : There's quite a lot of elements in that music and in that culture that we have a little similarity with, but there you get a purer strain of it. It's a little more intense.

Tina Weymouth : Some days, Eno would come in in a bad mood, and he would just lay his bad mood over everybody. Instead of being busiensslike and professional, instead of saying, ‘OK, I leave my personal problems behind,’ he brought all that in too. ‘Oooh, stomach ache!’ ‘Oh, this sounds stupid to me - I’m going to erase everything except the drums.’

Brian Eno : You have to realize that, even subtracting the irritant of my presence from the situation, this was a band going through an intense internal upheaval. I feel that I became a scapegoat for much of the bad feeling that was generated then, but I also see this as a way for them to exonerate each other and thus find a way to work together again.

Tina Weymouth : When David gives orders, all he does is make the whole thing grind to a halt. That’s what both Eno and David did by trying to prove they were leaders. They almost brought the whole thing to a halt.

Nona Hendryx : I think Tina felt that Eno was getting credit for something that they were already a part of, and building towards themselves. Working with people who have a very strong ego - and we all have ego, it’s nothing detrimental to talk about - they’re going to clash at some point, because it’s something that needs constant feeding.

Tina Weymouth : By the time they (Byrne and Eno) finished working together for three months, they were dressing like one another. They’re like two fourteen year old boys making an impression on each other. It was like they switched shoes. Eno was now wearing Thomas McAnn slip-ons.

Brian Eno : At the end of the recording, there was great confusion as to how royalties should be divided. It was quite difficult to assess what share each person had in the genesis of any piece, particularly when instruments that had been important to the original conception and evolution of the piece, had subsequently been replaced by new parts as the piece developed. What was especially difficult was assessing one’s own role in the process fairly. Naturally, everybody felt their particular contribution to have been particularly important.

I had an idea for a way to divide royalties - each person apportions credit tothe other four, but not to him- or herself … By this process, each person’s contribution has been assessed by the other four members, but not by him- or herself. If you then add these up, you get an overall royalty division … Now, by dividing each figure by five, you attain a percentage figure for the division.

It was on this basis, and nobody had a better idea at the time, that the composers’ royalties for Remain In Light were divided. I still believe that this was a fair system. As regards the credits on the album sleeve, all of the music was written in varying degrees by all of the members of the band and myself. It was therefore fair to include me among the composer credits. However David, who did after all write most of the vocal melodies and nearly all of the lyrics, felt that he too should be individually named in the credits.

Tina Weymouth : We’d taken a vote and decided we’d all written stuff; all five names were supposed to go on. Then, when the test-pressing cover came back, there were only two names. We raised a stink about it, and David took the blame. About two years later, I found out Eno pushed him to do it.

Eno called up David and said, ‘I really think this is unfair. I really think I did more work, and so I think you and I should get all the credit.’ Poor David got yelled at by a lot of people as a result, but Brian and David were really into this credit thing, I guess.

Chris Frantz : It wasn’t an administrative error. It was an error by a member of the band who is used to taking credit for everything that happens. And when it was put to him that this was not the right way to do things, he had to admit that it wasn’t.

Brian Eno : On reflection, it may have been diplomatic to have listed all of our names, but I don’t think it would have been more fair. The formula arrived at was tactless, but accurate.

Tina Weymouth : And we never said,’The band’s breaking up,’ to each other. The problem went away because Eno went away.

Chris Frantz : A lot of people don’t realize this, but Remain In Light was the worst-selling Talking Heads record ever.

David Byrne : Financially, we took a beating on that one. At the time it was a really hard sell. The reaction that we heard was that it sounded too black for white radio and too white for black radio.

Chris Frantz : It got great critical acclaim,and we felt that it kind of took popular music to the next phase, which is what we always wanted to do.

Vernon Reid (guitarist, Living Colour) : I think I heard it on a radio station. I was like, what the hell is this? I was intrigued completely by the sound of it. It just sounded so different from other things around it.

It was an evolution of the coming together of African music, electronics, funk and a kind of post-punk new wave, a culmination of things that had already been in the air.

REMAIN IN LIGHT - SONG BY SONG

THE GREAT CURVE

David Byrne : I’m not talking about one particular woman. I’m not talking about my girlfriend. You think that’s very down and earthy, but I was talking about something metaphysical. That a gesture can resonate outward, like ripples in a pond, causing realms of meaning. An attitude of the body can embody a whole world view.

ONCE IN A LIFETIME

David Byrne : This is one of the songs where you do a cinematic jump cut, an abrupt transition from one sensibility to a completely different one. Then you put the two next to each other, and they play off one another. In this case, the man was bewildered: Where and how did I get here? And in the chorus, the same man seems to have found blissful surrender coming out from under water, water washing over him - blissful surrender in the Islamic sense.

Tweet this Fact

He has said, for example, that, “We were really intrigued and excited by the formal aspects of Afican music.” She, however, insisted, “No-one discussed with us the fact that we were going to be playing in an African style.”

Nevertheless, what they created was a whole new direction, not just for Talking Heads but for 80s rock in general. With the quartet expanded by the addition of horns, extra percussion and voices, they moved away from traditional songwriting by improvising songs in the studio, diving headlong into the complexities of African polyrhythms and replacing Byrne’s urban paranoia with much more affirmative lyrics.

“I think the music was important in that,” says Byrne. “The anxiety of my lyrics and my singing didn’t seem appropriate to this kind of music. This music is more positive, though a little mysterious at the same time.”

The other vital ingredient was Eno, taking a much more active part in the music here than on previous Talking Heads albums. Eno’s fingerprints are everywhere, from vocal harmonies and counterpoints to layered ambient sounds, lyrics and rhythmic devices. Guitarist Chris Frantz confirms that “The barriers between musician and producer were being broken down ‘cause we were writing the songs in the studio.”

“An album of brave inventions and haunting textures,” drooled NME on release, but Rolling Stone nailed it even better with “Scary, funny music to which you can dance and think, think and dance, dance and think, ad infinitum.”

Predictably, though, the world wasn’t ready for doing two things at once. “It was the worst-selling Talking Heads album ever,” points out Frantz. Tightly formatted American radio found it impossible to programme because, as Byrne recalls, “The reaction we heard was that it sounded too black for white radio and too white for black radio.”

By the end of the 80s, however, Remain In Light featured at No4 in Rolling Stone’s selection of the decade’s greatest albums, and it continues to attract new converts to its irresistably quirky stew of traditional and avant-garde elements.

REMAIN IN LIGHT : THE ORAL HISTORY

Brian Eno (producer) : I was initially reluctant to produce Remain In Light. I had been working for some months with David on My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, and my mind was still very much in that record. I agreed to work with the band on generating some new material, but I suggested they find another producer.

Tina Weymouth (Talking Heads) : Brian hadn’t even stayed to finish Bush Of Ghosts. Something happened between him and David. We asked him to work on Remain In Light and at first he was reluctant. I really don’t know what went down between them.

Jerry Harrison (Talking Heads) : Remain In Light was almost like recording rehearsals. You might say it was started with a concept, part one of which was tobe able to capture (and sometimes keep) mistakes that happen right when you start something. Part two was to create sections by building up parts and polyrhythms. Sometimes you can get too caught up in doing arrangements, and this was a way of opening up.

Tina Weymouth : When we were making Speaking in Tongues and Remain in Light we were jamming and from that we were taking the best bits and then recording those and then improvising on top of those, the vocals and the melody, the lyric and all that.

Brian Eno : After a few days of playing together, the band, and in particular Chris and Tina, requested very forcefully that I reconsider producing the record. I said that I would do it willingly, on condition that they accepted that I would treat it as I treated my own work - that’s to say as a continuation of the ideas I’d been involved with on My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts.

I explained as carefully as I could that this would not be a production in the usual sense, that I was only interested in pushing certain musical ideas at the moment and that, if I were producing their record, I would pursue those ideas there. I believe I could not have been more clear about this.

The band understood and accepted what I said. They replied that the ideas I had outlined were not, anyway unfamiliar to them. This was indeed true - they were extensions of what we’d already done on previous records - and that they were in sympathy with the idea of pursuing a rather exclusive objective such as I’d described. They also urged me totreat the album as a collaboration rather than as a simple production, and it was on this basis we proceeded.

David Byrne : I think she (Tina) was understandably upset that Brian and I were pushing this whole direction so adamantly. It was almost like it was a train out of control or something. Maybe she felt she wasn’t a part of that. She was a part of it, but I can understand how she might have felt.

Brian Eno : I wouldn't call myself the fifth Head or any other number Head.

Jerry Harrison : We deliberately switched instruments, because sometimes people can come up with a naïve part that somebody else might not come up with. On some things, I started out playing drums, with Chris playing synthesiser, and later we switched back. That works quite well as a way of getting away from the things you fall into, in addition to being fun.

David Byrne : It’s essential that, when you listen to it, it has some effect on your body - whether you stand up and dance to it or not. It’s up to you. When we were working in the studio that was always my criterion for judging a part - whether it did something to the piece that makes you want to move your body in a more interesting way. You can use your body as much as a judge of the various parts as you do your ears.

Chris Frantz : Remain In Light was a difficult album to make. We wanted to do something ground-breaking, but we didn’t want to get into fights about it. And a couple of times, we did get into fights - musical fights - because somebody wanted to go one way and another person thought it shouldn’t sound like that.

David Byrne (Talking Heads) : We wanted to develop an understanding of the African musical concept of interlocking, interdependent parts and rhythms that combine to make a coherent whole. It’s completely different from playing rock songs; it’s not just a band executing a tune.

Tina Weymouth : David had such a completely different theory about it. His theory was far more intellectual and bookish. I never felt that there was any conscious, manipulative effort on our part to play African styles. To me and Chris, it seemed as if that importance was attached to the record after the fact. They (Byrne and Eno) were very keen on some literature they’d been reading…

David Byrne : There was actually only one that I was reading during the making of the record. And I felt that had had something to do with what we were doing.

The only one that had directly to do with music was the one called African Rhythms And African Sensibility by this fellow, John Miller Chernoff. Then there was African Art And Motion, which is about how the art works with the dancing and the rituals. That’s by Robert Farris Thompson.the other one was The Divine Horseman, a book about voodoo in Haiti, by this woman, Maya Dering, who used to be a film-maker and who, in later years, got wrapped up in voodoo.

Those books helped me put together ideas that I was already having about the way music expresses the culture it comes from. That seems like a real obvious idea, it’s nothing new. But it somehow became clearer to me, I had a lot clearer idea of how it works. That was exciting for me because, as we were doing bits of music or recording things, I could hear a lot of implications in different musical parts - social implications and political implications and whatnot.

Tina Weymouth : I suppose we were all quite aware of African music sometime before that. But no-one discussed with us the fact we were going to be playing in an African style. To us, it was all very funny, putting this bibliography together with a record. It’s so pseudo-intellectual, and everything we were trying to get away from.

David Byrne : I just thought they were good books,and at least one of them had a lot of influence on me. So I just thought I’d pass along that information.

David Byrne : Born Under Punches, that was real spontaneous, just improvised in the studio, spontaneous emissions.

Tina Weymouth : It was the beginning of David finding a way to improvise very quickly in the studio. Before, it had been a very private kind of struggle.

David Byrne : Eno gave me confidence in the studio. He encouraged me to go in with nothing prepared.

I feel less afraid of many things now, feel more confident. And I think the music was important in that. It demanded a completely different attitude. The anxiety of my lyrics and my singing didn’t seem appropriate to this kind of music. This music is more positive, though a little mysterious at the same time. So it was important that I wrote lyrics that also had these qualities.

David Byrne : We (Byrne and Eno) both grew up listening to music that had its roots in Africa. The African music we listen to isn't that different - in spirit, anyway - than a lot of rhythm and blues, or funk, that we're quite accustomed to and that most of Talking Heads' music is based on. It's not that big a leap."

Brian Eno (producer) : It has melodies you can understand, rhythms you can understand. The other thing about Africa is that both of us, and many other people in the world, are interested in discovering whether there are other moral philosophies - not a word one bandies lightly in the contemporary rock press, I must say.

The way I see it, during the '50s and '60s people were very impressed by Eastern philosophies because they seemed to represent another option about how you could think about or organize things, your life being one of them. They also had an important musical connection; there was a whole group of composers, both rock and 'serious,' who were very influenced by Eastern ideas. It's become a rather unpleasant part of the currency of '70s thinking.

We were both attracted to the African thing initially for music reasons. We began reading about African music at first but you can't read about African music without finding out about African society because they're so closely interwoven. Music stands as a crystallization of cultural standards.

Nona Hendryx (vocalist, Remain In Light) : I think David really liked African rhythms and music. It’s something he was instinctively drawn to.It was a risk, getting into African rhythms and sounds and being a white person, expressing it as something coming from him.

David Byrne : There's a very different kind of spirituality in Africa than what we grew up with. As opposed to our "sober, very serious" approach, in Africa and a lot of other cultures, probably most of the cultures in the world, things that are considered spiritual - performances, music - are also exciting and fun. People have a good time; it's not sacred in the sense that you can't talk while a performance is going on, or have a drink or smoke a cigarette. There isn't that separation of pleasure and spiritual things.

Brian Eno : All the Talking Heads and myself have been listening to African records. You can't steer anyone in a direction they're not already going in; there has to be momentum or it isn't going to succeed. David and I did articulate a way of working - we said, 'This is the way we want to work,' rather than all other possible ways - but it wasn't an idea that was foreign to everyone, Nobody said, 'God, what's this?' "

David Byrne : It was more a case of everyone going, 'Oh yeah, exactly.” I think it was something that everyone in the band was interested in to some degree, but Brian and myself were more actively involved in reading books and listening to records.

Brian Eno : We weren't trying to do African music. We were trying to use some of the things we thought we'd learn from that in making a newer version of our own music. I don't think it's like putting on a new set of clothes and 'here we are, it 's all new.' It's saying, 'This might be a clearer version of what we've been trying to do anyway' - or a more refined version.

David Byrne : I saw more and more similarities between African music and black American music. I thought yes, it's discontent with a lot of white music and a lot of the sensibility that white music is about, but [African music] is not as exotic as it initially sounds.

Brian Eno : Also, it's not so much that you go to another culture to discover

some thing entirely new; it's to discover a different emphasis on things. I

think we were interested in finding some way to emphasize different aspects,

not suddenly to present us with a whole lot of new ones. Most of the things we ran into as we were reading and listening were not totally exotic but a different balance - a balance that seemed quite attractive to us.

David Byrne : There's quite a lot of elements in that music and in that culture that we have a little similarity with, but there you get a purer strain of it. It's a little more intense.

Tina Weymouth : Some days, Eno would come in in a bad mood, and he would just lay his bad mood over everybody. Instead of being busiensslike and professional, instead of saying, ‘OK, I leave my personal problems behind,’ he brought all that in too. ‘Oooh, stomach ache!’ ‘Oh, this sounds stupid to me - I’m going to erase everything except the drums.’

Brian Eno : You have to realize that, even subtracting the irritant of my presence from the situation, this was a band going through an intense internal upheaval. I feel that I became a scapegoat for much of the bad feeling that was generated then, but I also see this as a way for them to exonerate each other and thus find a way to work together again.

Tina Weymouth : When David gives orders, all he does is make the whole thing grind to a halt. That’s what both Eno and David did by trying to prove they were leaders. They almost brought the whole thing to a halt.

Nona Hendryx : I think Tina felt that Eno was getting credit for something that they were already a part of, and building towards themselves. Working with people who have a very strong ego - and we all have ego, it’s nothing detrimental to talk about - they’re going to clash at some point, because it’s something that needs constant feeding.

Tina Weymouth : By the time they (Byrne and Eno) finished working together for three months, they were dressing like one another. They’re like two fourteen year old boys making an impression on each other. It was like they switched shoes. Eno was now wearing Thomas McAnn slip-ons.

Brian Eno : At the end of the recording, there was great confusion as to how royalties should be divided. It was quite difficult to assess what share each person had in the genesis of any piece, particularly when instruments that had been important to the original conception and evolution of the piece, had subsequently been replaced by new parts as the piece developed. What was especially difficult was assessing one’s own role in the process fairly. Naturally, everybody felt their particular contribution to have been particularly important.

I had an idea for a way to divide royalties - each person apportions credit tothe other four, but not to him- or herself … By this process, each person’s contribution has been assessed by the other four members, but not by him- or herself. If you then add these up, you get an overall royalty division … Now, by dividing each figure by five, you attain a percentage figure for the division.

It was on this basis, and nobody had a better idea at the time, that the composers’ royalties for Remain In Light were divided. I still believe that this was a fair system. As regards the credits on the album sleeve, all of the music was written in varying degrees by all of the members of the band and myself. It was therefore fair to include me among the composer credits. However David, who did after all write most of the vocal melodies and nearly all of the lyrics, felt that he too should be individually named in the credits.

Tina Weymouth : We’d taken a vote and decided we’d all written stuff; all five names were supposed to go on. Then, when the test-pressing cover came back, there were only two names. We raised a stink about it, and David took the blame. About two years later, I found out Eno pushed him to do it.

Eno called up David and said, ‘I really think this is unfair. I really think I did more work, and so I think you and I should get all the credit.’ Poor David got yelled at by a lot of people as a result, but Brian and David were really into this credit thing, I guess.

Chris Frantz : It wasn’t an administrative error. It was an error by a member of the band who is used to taking credit for everything that happens. And when it was put to him that this was not the right way to do things, he had to admit that it wasn’t.

Brian Eno : On reflection, it may have been diplomatic to have listed all of our names, but I don’t think it would have been more fair. The formula arrived at was tactless, but accurate.

Tina Weymouth : And we never said,’The band’s breaking up,’ to each other. The problem went away because Eno went away.

Chris Frantz : A lot of people don’t realize this, but Remain In Light was the worst-selling Talking Heads record ever.

David Byrne : Financially, we took a beating on that one. At the time it was a really hard sell. The reaction that we heard was that it sounded too black for white radio and too white for black radio.

Chris Frantz : It got great critical acclaim,and we felt that it kind of took popular music to the next phase, which is what we always wanted to do.

Vernon Reid (guitarist, Living Colour) : I think I heard it on a radio station. I was like, what the hell is this? I was intrigued completely by the sound of it. It just sounded so different from other things around it.

It was an evolution of the coming together of African music, electronics, funk and a kind of post-punk new wave, a culmination of things that had already been in the air.

REMAIN IN LIGHT - SONG BY SONG

THE GREAT CURVE

David Byrne : I’m not talking about one particular woman. I’m not talking about my girlfriend. You think that’s very down and earthy, but I was talking about something metaphysical. That a gesture can resonate outward, like ripples in a pond, causing realms of meaning. An attitude of the body can embody a whole world view.

ONCE IN A LIFETIME

David Byrne : This is one of the songs where you do a cinematic jump cut, an abrupt transition from one sensibility to a completely different one. Then you put the two next to each other, and they play off one another. In this case, the man was bewildered: Where and how did I get here? And in the chorus, the same man seems to have found blissful surrender coming out from under water, water washing over him - blissful surrender in the Islamic sense.