Fact #148406

When:

Short story:

Full article:

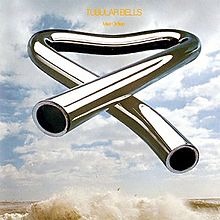

MIKE OLDFIELD - TUBULAR BELLS

by Johnny Black

Tubular Bells was a music industry ground-breaker of gigantic proportions, cobbled together by a teenage guitar geek.

Oldfield would be the first to admit that he was something of a social misfit, a prodigiously talented young musician whose guitar was his life. He didn’t set out to create an album that would expand the horizons of electric guitar as none had done since Hendrix, or an album that would break every rule about how to make hit records, or an album that would make it possible for rock composers to be spoken of with the same respect as classical composers, but he achieved all three just by doing what came naturally to him.

The seed of Tubular Bells was sown on 10 July, 1971, when Kevin Ayers And the Whole World played their final gig together in London, leaving their sixteen year old guitarist Mike Oldfield out of a job. Ayers, however, had also given the lad his key to fame and fortune, an old Bang & Olufsen tape recorder.

“By soldering a few wires together and blocking off the tape with cigarette packets and things,” recalls Oldfield, “I was able to multi-track on it. I took the insides out and did all kinds of strange things with tape loops and decided that I'd better have one of these Terry Riley things in there to start my very first demo. And that was the opening theme for Tubular Bells, which I played on a Farfisa organ.”

Oldfield lugged his lo-fi, wart’n’all demo round to the smart offices of several top record company A&R men, only to find that, “They all looked at me as if I was mad. They all said, because there were no vocals, no words, no drums or anything, that it was not marketable.” And, in a year when the British charts were dominated by the likes of Donny Osmond, David Cassidy and Gilbert O’Sullivan, who could blame them?

Indeed, it might all have ended right there, if Oldfield’s next group, the Arthur Lewis Band, hadn’t been chosen by chance to make some test recordings at the soon-to-open Virgin Manor studio in Oxfordshire. During some down time in the Manor, Oldfield played his demo for studio boss Tom Newman. “He was just a funny little hippie,” recalls Newman, but he was sufficiently impressed to allocate the lad some recording time.

So, in late 1972, Oldfield squirreled himself away in the bowels of The Manor and set to work in earnest, piecing Tubular Bells together from what Newman had first heard as “half a dozen little unconnected pieces”, and playing virtually all the instruments himself. As he remembers it, ”I made up a list for Virgin of all the instruments I would need, and they ordered everything up for me. I had seen a set of tubular bells when I did some recording in Abbey Road, so I thought I may as well have some tubular bells, they might come in handy.”

Although The Manor was being built from scratch as a state of the art recording facility, this was an era when such now standard techniques as cross-fading and drop-ins simply didn’t exist, and when editing of tracks was done by cutting up the tapes with a razor blade. From the start, Oldfield pushed the existing technology to its limits. “I remember, on the second day of actual recording, explaining to Tom that I had this organ chord which I wanted to slowly slide into another chord,” he says. “It would be simplicity itself with modern synths, but the only way we could do it then was to get the maintenance engineer to come in and record the first organ chord on a tape loop, which he then put onto this great big machine with a huge dial on it and, as he turned the dial, the machine sped up which caused the chord to go up in pitch.”

Tom Newman has vivid memories of some of the Heath Robinson-like contraptions Oldfield used to achieve his guitar effects. “He had this awful home-made electronics box full of horrid transistors, covered in faders and knobs, which he called his Glorfindel. It was a piece of plywood filled with junk that he could plug his guitar into and sometimes a sound would come out. Most of the time it was terrible. It would go ‘Eeeeoww” Arrrk!’ It was like tuning a radio set. Then he would kick it and all of a sudden this glorious, amazing guitar sound would come out.”

Much of the actual recording was carried out late at night, after the imbibing of far too much Guinness at the local hostelry. As a result, entire days of recording were sometimes wiped by accident and, as Oldfield readily admits, the tubular bells themselves were somewhat the worse for wear by the time they were put on tape.

“Instead of using the little mallet provided, I hit the bell using a proper metal hammer,” he explains, “because I wanted it to sound much bigger. I really wanted a huge cathedral bell, but all we had was these little bells. Anyway, I hit it so hard that I cracked it and there was so much gain wound up on the microphone channel that there's noticeable distortion.”

On hearing the completed masterwork, Virgin supreme Richard Branson was far from convinced. According to Newman, getting his boss to release the record “was like dragging stuff uphill through treacle.”

In due course, though, Newman won Branson over and Tubular Bells entered the UK album chart on 14 July 73. It wasn’t, however an overnight smash, but persistent marketing kept it moving up until it finally reached No on 5 October 1974 – one week after its follow-up, Hergist Ridge.

Ultimately, it became the second best-selling UK album of the seventies, outsold only by Simon And Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water. And, as if to prove all those doubting A&R men wrong, after Tubular Bells appeared in the soundtrack of the film The Exorcist, an edited excerpt became a US Top 10 single.

(Source : Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums by Backbeat Books, 2007)

Origins of Virgin Records

Quite apart from the innovative characteristics of the music, Tubular Bells has a second claim to rock’n’roll greatness. Being the first record released by Virgin Records, it was also the start of the Richard Branson empire which has since blossomed into a global conglomerate built on megastores, airlines, railways, telecommunications and more.

Branson, having left school with three O-levels, founded Virgin as a cut-price mail order record store, but it was unquestionably the massive sales generated by Tubular Bells which transformed the toothy-grinned charmer into a business mogul, who went on to sell Virgin Records to EMI in March 1992 for £560 million.

Branson’s canny business instincts remain his empire’s greatest asset, although his clever manipulation of his own image runs it a close second. He knows that to be seen abseiling down the side of Centre Point, or ballooning across the world’s oceans, brings the kind of advertising money can’t buy.

Pegged early on as “the hip capitalist”, he is notorious for knowing nothing about music. “It was a bit beyond him,” says Oldfield, who points out that Branson’s real gift was for employing people who did know what they doing. Those people signed Phil Collins, Culture Club, the Sex Pistols and countless other acts that made Richard richer than any of them.

(Source : Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums by Backbeat Books, 2007)

Tweet this Fact

by Johnny Black

Tubular Bells was a music industry ground-breaker of gigantic proportions, cobbled together by a teenage guitar geek.

Oldfield would be the first to admit that he was something of a social misfit, a prodigiously talented young musician whose guitar was his life. He didn’t set out to create an album that would expand the horizons of electric guitar as none had done since Hendrix, or an album that would break every rule about how to make hit records, or an album that would make it possible for rock composers to be spoken of with the same respect as classical composers, but he achieved all three just by doing what came naturally to him.

The seed of Tubular Bells was sown on 10 July, 1971, when Kevin Ayers And the Whole World played their final gig together in London, leaving their sixteen year old guitarist Mike Oldfield out of a job. Ayers, however, had also given the lad his key to fame and fortune, an old Bang & Olufsen tape recorder.

“By soldering a few wires together and blocking off the tape with cigarette packets and things,” recalls Oldfield, “I was able to multi-track on it. I took the insides out and did all kinds of strange things with tape loops and decided that I'd better have one of these Terry Riley things in there to start my very first demo. And that was the opening theme for Tubular Bells, which I played on a Farfisa organ.”

Oldfield lugged his lo-fi, wart’n’all demo round to the smart offices of several top record company A&R men, only to find that, “They all looked at me as if I was mad. They all said, because there were no vocals, no words, no drums or anything, that it was not marketable.” And, in a year when the British charts were dominated by the likes of Donny Osmond, David Cassidy and Gilbert O’Sullivan, who could blame them?

Indeed, it might all have ended right there, if Oldfield’s next group, the Arthur Lewis Band, hadn’t been chosen by chance to make some test recordings at the soon-to-open Virgin Manor studio in Oxfordshire. During some down time in the Manor, Oldfield played his demo for studio boss Tom Newman. “He was just a funny little hippie,” recalls Newman, but he was sufficiently impressed to allocate the lad some recording time.

So, in late 1972, Oldfield squirreled himself away in the bowels of The Manor and set to work in earnest, piecing Tubular Bells together from what Newman had first heard as “half a dozen little unconnected pieces”, and playing virtually all the instruments himself. As he remembers it, ”I made up a list for Virgin of all the instruments I would need, and they ordered everything up for me. I had seen a set of tubular bells when I did some recording in Abbey Road, so I thought I may as well have some tubular bells, they might come in handy.”

Although The Manor was being built from scratch as a state of the art recording facility, this was an era when such now standard techniques as cross-fading and drop-ins simply didn’t exist, and when editing of tracks was done by cutting up the tapes with a razor blade. From the start, Oldfield pushed the existing technology to its limits. “I remember, on the second day of actual recording, explaining to Tom that I had this organ chord which I wanted to slowly slide into another chord,” he says. “It would be simplicity itself with modern synths, but the only way we could do it then was to get the maintenance engineer to come in and record the first organ chord on a tape loop, which he then put onto this great big machine with a huge dial on it and, as he turned the dial, the machine sped up which caused the chord to go up in pitch.”

Tom Newman has vivid memories of some of the Heath Robinson-like contraptions Oldfield used to achieve his guitar effects. “He had this awful home-made electronics box full of horrid transistors, covered in faders and knobs, which he called his Glorfindel. It was a piece of plywood filled with junk that he could plug his guitar into and sometimes a sound would come out. Most of the time it was terrible. It would go ‘Eeeeoww” Arrrk!’ It was like tuning a radio set. Then he would kick it and all of a sudden this glorious, amazing guitar sound would come out.”

Much of the actual recording was carried out late at night, after the imbibing of far too much Guinness at the local hostelry. As a result, entire days of recording were sometimes wiped by accident and, as Oldfield readily admits, the tubular bells themselves were somewhat the worse for wear by the time they were put on tape.

“Instead of using the little mallet provided, I hit the bell using a proper metal hammer,” he explains, “because I wanted it to sound much bigger. I really wanted a huge cathedral bell, but all we had was these little bells. Anyway, I hit it so hard that I cracked it and there was so much gain wound up on the microphone channel that there's noticeable distortion.”

On hearing the completed masterwork, Virgin supreme Richard Branson was far from convinced. According to Newman, getting his boss to release the record “was like dragging stuff uphill through treacle.”

In due course, though, Newman won Branson over and Tubular Bells entered the UK album chart on 14 July 73. It wasn’t, however an overnight smash, but persistent marketing kept it moving up until it finally reached No on 5 October 1974 – one week after its follow-up, Hergist Ridge.

Ultimately, it became the second best-selling UK album of the seventies, outsold only by Simon And Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water. And, as if to prove all those doubting A&R men wrong, after Tubular Bells appeared in the soundtrack of the film The Exorcist, an edited excerpt became a US Top 10 single.

(Source : Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums by Backbeat Books, 2007)

Origins of Virgin Records

Quite apart from the innovative characteristics of the music, Tubular Bells has a second claim to rock’n’roll greatness. Being the first record released by Virgin Records, it was also the start of the Richard Branson empire which has since blossomed into a global conglomerate built on megastores, airlines, railways, telecommunications and more.

Branson, having left school with three O-levels, founded Virgin as a cut-price mail order record store, but it was unquestionably the massive sales generated by Tubular Bells which transformed the toothy-grinned charmer into a business mogul, who went on to sell Virgin Records to EMI in March 1992 for £560 million.

Branson’s canny business instincts remain his empire’s greatest asset, although his clever manipulation of his own image runs it a close second. He knows that to be seen abseiling down the side of Centre Point, or ballooning across the world’s oceans, brings the kind of advertising money can’t buy.

Pegged early on as “the hip capitalist”, he is notorious for knowing nothing about music. “It was a bit beyond him,” says Oldfield, who points out that Branson’s real gift was for employing people who did know what they doing. Those people signed Phil Collins, Culture Club, the Sex Pistols and countless other acts that made Richard richer than any of them.

(Source : Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums by Backbeat Books, 2007)