Fact #140175

When:

Short story:

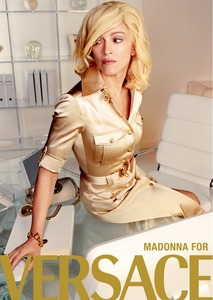

It is announced that Madonna and promoters Live Nation have signed a deal with secondary ticketing companies Stubhub and Viagogo making them the official secondary ticketing companies for Madonna's upcoming Sticky And Sweet world tour.

It is announced that Madonna and promoters Live Nation have signed a deal with secondary ticketing companies Stubhub and Viagogo making them the official secondary ticketing companies for Madonna's upcoming Sticky And Sweet world tour.Full article:

John Parker (account Director, MAndC Saatchi) : The Madonna, Jay-Z and U2 deals with Live Nation are an interesting evolvement of the traditional record deal. Free downloading means that the music created by artists is no longer the thing that earns them money. Tours, merchandise and other artiste-brand partnerships are where the money lies now.

(Source : interview with Johnny Black, for Live UK, 2008)

ROCK’N’ROLL TICKETING – HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?

By Johnny Black, 2008. This feature first appeared in Live UK magazine.

Just The Ticket?

Asked to sum up the music industry’s current relationship with the ticketing business in five words, SeeTickets’ MD Nick Blackburn instantly replies, “Confused.”

Pressed for his other four words, he laughs. “Just confused,” he repeats.

In the sixties, when The Beatles first rocketed British rock onto the international stage, ticketing was simplicity itself. “One of the very first tours I promoted was The Beatles in 1963,” remembers promoter Danny Betesh of Kennedy Street Enterprises. “Fans would buy a ticket for cash or cheque at the box office on a Saturday morning, and then come back to see the show. They didn’t even have credit cards, and the biggest venues even The Beatles played were theatres with a capacity of about 2,500.”

Today, however, the complexities of the ticketing business can be baffling for even the biggest, most alert and clued-up of music biz players. How did it get this way?

A Brief History of Ticketing

As the venerable Betesh recalls it, “When the big outdoor shows and festivals came along at the end of the 60s, mail order ticketing became more prevalent because people travelled further to get to the events.” This was also the era when increasing numbers of record shops started to become ticket outlets.

As the music business grew in the 70s, a small Arizona-based company called Ticketmaster started carving itself a considerable slice of the US market by using computers to speed up ticket processing.

The next major change for ticket buyers – the credit card - was ushered in during the 80s. And, just as the credit card hit Britain in a big way, so did the burgeoning Ticketmaster. “That was when ticketing agencies were investing in call centres,” points out Ticketmaster MD Chris Edmonds, “which completely changed the industry by enabling sales of large numbers of tickets quickly. One result of that was that promoters could put more concerts .”

Ticket agencies, of course, had long existed but until the arrival of Ticketmaster, they plied their trade by shifting the tickets the venues themselves couldn’t sell. Once Ticketmaster moved into high gear and established lucrative exclusive deals, an ever-increasing proportion of the revenue from live gigs was channelled through their coffers. The balance of power began to shift from promoters and venues to ticketing agencies.

According to Danny Betesh, “That’s very much how it continued almost until the turn of the century when the Internet took over.”

Hand in hand with the internet came eBay, providing a cheap and simple method whereby genuine ticket buyers who could no longer attend the gigs could re-sell their tickets. It wasn’t long before ticket touts spotted the potential for exploiting music fans via eBay and ticket re-sale prices started to rocket. Far worse, though, there was no control of the selling process and thousands of fans were conned into buying tickets that simply didn’t exist.

Something else that didn’t exist was the term secondary ticketing. That arrived in 2000, when two former Stanford Business School students, Jeff Fluhr and Eric Baker, started StubHub in the USA. “Before that it was called either touting or scalping,” observes Baker. “StubHub was the original secondary ticketing site.”

Secondary ticketing, as we’ll see later, has developed into the most controversial sector of the UK’s live market, but the booming primary sector is certainly not without its own share of hot topics.

Primary concerns

In December 2007, top promoter Harvey Goldsmith made his feelings about the rise and rise of primary agencies like Ticketmaster and SeeTickets absolutely clear, declaring them, “an evil made necessary by computerisation and the internet. These big agencies tend to charge well over the odds for handling, postage and credit card transactions. They earn more than the promoter – to the expense of the consumer.'

In fact, British ticketing charges are noticeably less inflated than in America, where building facility fees, convenience fees and order processing charges can boost ticket prices by a third, even before the addition of ‘optional express postage’ and parking fees.

Nevertheless, there are many in the UK who share Goldsmith’s concerns, although his wrath is clearly unwelcome at Ticketmaster, who currently sell 15m tickets a year. MD Chris Edmonds argues, “The booking fee is the sole source of revenue for a ticketing agency. It covers not just the actual sales process to the consumer, but our investment in ticketing technology and the website plus our marketing costs.” Edmonds cites, as examples, the 4m e-mails Ticketmaster sends out every week promoting events and the infrastructure which enables the company to smoothly handle problems arising from cancelled or re-scheduled gigs.

“We are totally transparent in our charges,” says Nick Blackburn at SeeTickets. “There’s the booking fee, the transaction fee and that’s it. Sometimes we don’t even charge a booking fee if we get inside commission, as we do on The Sound Of Music and Joseph, but that doesn’t happen in rock shows.”

Chris Edmonds at Ticketmaster adds, “the actual level of fees is not a huge issue to consumers, as long as they get a good experience and they know that when they’ve bought those tickets they will arrive in time for the event.”

Others, including proponents of mobile ticketing, however, note that many of the fees currently charged – notably postage and packing – vanish when the ticket is delivered digitally.

Ramesh Kumar of mobile ticketers Tixmob says “We have a ticket price and a booking fee, no extras, not even delivery fees, because we’re not posting anything.”

Today’s Ticketing Choices

Kumar’s point is timely, because the humble and once universal gig ticket is fast becoming an endangered species, as a raft of new approaches vie for the affections of the public.

The traditional, well-established agencies still deal in significant numbers of physical tickets, either posted out or collected at the venue, but recent technological advances have enabled appealing alternatives.

Print At Home, for example, offers ticket data e-mailed to the customer as a printable barcode, which is then scanned at the venue. “The public do seem to like print at home,” observes Nick Blackburn. “I think it’s a good technology but it requires scanners in the venues, and a lot of places can’t afford them.”

“I’m not a fan of print at home,” declares Mark Gasson of the Nottingham-based agency Gigantic. “It’s a barcode system, so what’s to prevent someone printing that e-mail out ten times and selling it on? Then the first person who turns up gets in, but nobody else.”

Like Tixmob, the Edinburgh-based Mobiqa has been finding significant acceptance for its mobile-phone-based alternative, the MobiTicket. “Our technology delivers a barcode by SMS to your mobile phone,” says Mobiqa Director Don Cameron, “It’s the same as on a print at home ticket, plus information about the artist, venue and time.”

Scanned at the venue directly from a phone’s screen, MobiTickets were used successfully as one option for the recent Ticketmaster/Live Nation gigs at Hyde Park.

It might surprise many to learn that innovative use of bargain basement digital technology is also benefiting some of the smallest venues on the live circuit. When Dave Newton, founder of Shifty Disco Records, set up a gig for The Unbelievable Truth at The Bull And Gate in Kentish Town in April 2000, he accidentally launched himself as a ticketing agency.

“I knew there were people who wanted to come from outside London for that gig but the ticket price was low, so mailing out tickets would have put the price up considerably,” he recalls. His solution was to use Shifty Disco’s online shop to e-mail tickets in the form of a numeric code which out-of-town fans brought to the gig where it was checked against a list.

Soon after, Newton realised his hastily-improvised system had greater potential. “Ticketmaster and SeeTickets were soaking up 95% of the tickets in the UK, but they start at a certain level,” he says. “Their pricing structure isn’t viable for tickets under £10. With booking fees and delivery charges and transaction charges, a £10 ticket ends up costing £16.”

Newton’s system has since blossomed with the addition of software which allows small gig promoters to log their gigs onto his site, wegottickets.com, thus selling tickets to customers they previously would not have reached. “We now have about 4,000 promoters registered with us, and our biggest single event so far was probably the 3000 tickets we sold for the 2008 Truck Festival.”

A similar idea lies at the heart of Matt McNeill’s Fulham-based company e-Tickets, which scooped the Innovative Business of The Year Award at the 2004 Natwest Startup Awards. “I couldn’t see why the existing agencies charged such high fees when so much of what they do is now automated,” he explains. McNeill’s system differs from wegottickets.com in that rather than a %, he charges promoters a flat rate per ticket sold. At the smaller venue level (up to 1000 capacity), promoters can choose his self-service option, but for larger events he tailors his service to match the needs of the client. “We’re now trading globally,” he reveals, “doing 12,000 tickets for the exit festival in Serbia and 20,000 for the Rhythm And Vines festival in New Zealand.” Is it any surprise he was named one of the top 10 business entrepreneurs to watch in the 2007 Courvoisier Future 500?

It’s not just the appearance and format of tickets that is changing. Many companies want to change the way the business thinks about tickets. Mark McLaughlin, co-founder of the Dublin-based Ticket-Text.com explains, “We are a low-cost mobile and e-ticket agency, but it’s not about the ticket. It’s about everything else you can do when you know more about your customers.”

For McLaughlin and others of like mind, the biggest advantage of a digitally delivered ticket is that the information collected along the way adds up to a database of knowledge about a venue’s customers which can be used to sell them other products and services.

New Kids On the Block

Alongside all of these technological innovations, the primary ticket market is also having to adapt to changes in its basic structure.

Potentially most significant of all, the dominance of agencies like Ticketmaster and SeeTickets in a booming live market will soon be challenged by the world’s largest promoter, Live Nation, which has opted to end its lengthy relationship with Ticketmaster and set up its own ticketing operation. Although Live Nation declined to comment on its plans for this feature, observers estimate that this move will make it the planet’s second biggest ticketing agency.

Ticketmaster’s Chris Edmonds, however, remains upbeat. “We’re very confident about Ticketmaster’s position in the market place, because we have a relationship with the consumer where they know they can come to us, they’ll be able to buy a ticket, they won’t get ripped off, and they’ll get good service.”

Another challenge to the ticket agency giants comes in the form of software developed by the Canadian company AudienceView, which is shaking things up at a number of major venue complexes around the UK. “AudienceView is about providing venues with control and an integrated suite of tools that is going to empower their business,” says Rob Edwards, VP Sales (Europe) of AudienceView Ticketing.

According to Edwards, as well as looking after transactions from low scale high volume, the software is capable of handling CRM (customer relationship management), marketing, data mining to inform marketing campaigns, fund-raising and membership subscriptions.

One evidently happy AudienceView customer is the NEC, which used the software to launch its own Ticket Factory last October. General Manager Saad Afzal says, “We knew that by leveraging our technology investment to become an independent, national ticket agent whilst retaining the customer-service ethos and ‘big-picture’ understanding of a venue box office, we could offer promoters and organisers a truly unique and compelling proposition.”

The NEC is not alone. AudienceView has also ‘empowered’ Sheffield Arena and the Liverpool Echo Arena. “The power of Ticketmaster And See is being challenged by a range of new entrants into the market,” says Saad Afzal, “ranging from small ticket brokers with website-only operations up to Live Nation.”

Smaller operations too are seeking to compete with the big boys in novel ways. Nottingham’s Gigantic, for example, are combining green virtues (they donate 10% of their booking fees to Oxfam) with a ‘small is beautiful’ ethic. “If you go onto Ticketmaster or SeeTickets on a Friday morning,” states MD Mark Gasson, “both sites are maxxed out, you can’t get through. We have pretty much the same tickets but, because we’re still the new guys, people can get onto us quickly.”

Another unexpected development has been the recent alliance of booking agency Primary Talent with SeeTickets. “It’s about empowering our artists with self-marketing tools,” explains MD Peter Elliott. Via their newly-established ArtistTicket.co.uk, Primary Talent’s artists now receive an allocation of tickets to sell through their own websites, with booking fees split between all three parties to the deal but, stresses Elliott, “The real heart of what this is about is the data which can help artists sell other products as well as tickets.”

Secondary ticketing

If any single issue has riven the live music industry it’s secondary ticketing.

“It is destroying the business….” insists Peter Elliott at Primary Talent, while Nick Blackburn at SeeTickets states, “I loathe it. It’s simply another word for touting.”

Eric Baker, founder of Viagogo, disagrees. “People have been re-selling tickets since the beginning of time,” he says. “I’m sure they re-sold tickets to Shakespeare’s plays. All we’re doing is making that transaction safe, secure and efficient.”

Just months ago, secondary ticketers like Viagogo, Seatwave and Get Me In were almost universally decried as little more than high tech ticket touts. They argued, however, that their sites had introduced stability and security into a market which, in its previous incarnation on eBay, was completely unregulated.

“The secondary ticketing market was one in which lots of people were spending lots of money,” says Seatwave founder Joe Cohen, “but the consumer experience was terrible. I felt we could build a service to provide a better consumer experience and bring prices down.”

Efforts to make the government pass legislation to control secondary ticketing – a market reckoned by sector analysts Tixdaq.com to be worth £200m a year – floundered.

With vast sums evidently at stake, some major players opted for pragmatic solutions. In January 2008 Ticketmaster bought Get Me In for a sum reportedly a little under £50m. In May, Madonna and Live Nation struck a deal with Viagogo who agreed to pay them a rights fee in return for becoming Madge’s official premium seat and secondary ticketer. In July, Seatwave became the official ticket re-saler for Grand Union Management.

These and other developments were perceived by many as legitimising secondary ticketing, and fears that such liaisons would push prices up were bolstered when the Tixdaq price comparison site reported that while £75 Madonna tickets were still available from Ticketmaster, identical tickets were being offered at up to £196 each by Viagogo.

Nevertheless, Andrew Blachman, CEO of Get Me In, is confident that, “Things are changing in our direction. Five years ago in the US a lot of people didn’t like secondary ticketing but now you’d be hard pressed to find a team or a league or an artist that isn’t participating in the secondary market. It took a while to happen over there but it seems to be happening a little faster here.”

There are, however, still many who feel that embracing secondary ticketing is a short-term solution at best, which will ultimately do more damage than good.

“You know, there is money to be made out of ticket re-sales in a legitimate way,” suggests Peter Elliott of Primary Talent. “Customers should be able to sell unwanted tickets back to the ticket agents who can re-sell it, or create some sort of ticket exchange, without a mark up. But the over-pricing, the middle man who doubles the ticket cost, that’s what’s killing the business.”

Tweet this Fact

(Source : interview with Johnny Black, for Live UK, 2008)

ROCK’N’ROLL TICKETING – HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?

By Johnny Black, 2008. This feature first appeared in Live UK magazine.

Just The Ticket?

Asked to sum up the music industry’s current relationship with the ticketing business in five words, SeeTickets’ MD Nick Blackburn instantly replies, “Confused.”

Pressed for his other four words, he laughs. “Just confused,” he repeats.

In the sixties, when The Beatles first rocketed British rock onto the international stage, ticketing was simplicity itself. “One of the very first tours I promoted was The Beatles in 1963,” remembers promoter Danny Betesh of Kennedy Street Enterprises. “Fans would buy a ticket for cash or cheque at the box office on a Saturday morning, and then come back to see the show. They didn’t even have credit cards, and the biggest venues even The Beatles played were theatres with a capacity of about 2,500.”

Today, however, the complexities of the ticketing business can be baffling for even the biggest, most alert and clued-up of music biz players. How did it get this way?

A Brief History of Ticketing

As the venerable Betesh recalls it, “When the big outdoor shows and festivals came along at the end of the 60s, mail order ticketing became more prevalent because people travelled further to get to the events.” This was also the era when increasing numbers of record shops started to become ticket outlets.

As the music business grew in the 70s, a small Arizona-based company called Ticketmaster started carving itself a considerable slice of the US market by using computers to speed up ticket processing.

The next major change for ticket buyers – the credit card - was ushered in during the 80s. And, just as the credit card hit Britain in a big way, so did the burgeoning Ticketmaster. “That was when ticketing agencies were investing in call centres,” points out Ticketmaster MD Chris Edmonds, “which completely changed the industry by enabling sales of large numbers of tickets quickly. One result of that was that promoters could put more concerts .”

Ticket agencies, of course, had long existed but until the arrival of Ticketmaster, they plied their trade by shifting the tickets the venues themselves couldn’t sell. Once Ticketmaster moved into high gear and established lucrative exclusive deals, an ever-increasing proportion of the revenue from live gigs was channelled through their coffers. The balance of power began to shift from promoters and venues to ticketing agencies.

According to Danny Betesh, “That’s very much how it continued almost until the turn of the century when the Internet took over.”

Hand in hand with the internet came eBay, providing a cheap and simple method whereby genuine ticket buyers who could no longer attend the gigs could re-sell their tickets. It wasn’t long before ticket touts spotted the potential for exploiting music fans via eBay and ticket re-sale prices started to rocket. Far worse, though, there was no control of the selling process and thousands of fans were conned into buying tickets that simply didn’t exist.

Something else that didn’t exist was the term secondary ticketing. That arrived in 2000, when two former Stanford Business School students, Jeff Fluhr and Eric Baker, started StubHub in the USA. “Before that it was called either touting or scalping,” observes Baker. “StubHub was the original secondary ticketing site.”

Secondary ticketing, as we’ll see later, has developed into the most controversial sector of the UK’s live market, but the booming primary sector is certainly not without its own share of hot topics.

Primary concerns

In December 2007, top promoter Harvey Goldsmith made his feelings about the rise and rise of primary agencies like Ticketmaster and SeeTickets absolutely clear, declaring them, “an evil made necessary by computerisation and the internet. These big agencies tend to charge well over the odds for handling, postage and credit card transactions. They earn more than the promoter – to the expense of the consumer.'

In fact, British ticketing charges are noticeably less inflated than in America, where building facility fees, convenience fees and order processing charges can boost ticket prices by a third, even before the addition of ‘optional express postage’ and parking fees.

Nevertheless, there are many in the UK who share Goldsmith’s concerns, although his wrath is clearly unwelcome at Ticketmaster, who currently sell 15m tickets a year. MD Chris Edmonds argues, “The booking fee is the sole source of revenue for a ticketing agency. It covers not just the actual sales process to the consumer, but our investment in ticketing technology and the website plus our marketing costs.” Edmonds cites, as examples, the 4m e-mails Ticketmaster sends out every week promoting events and the infrastructure which enables the company to smoothly handle problems arising from cancelled or re-scheduled gigs.

“We are totally transparent in our charges,” says Nick Blackburn at SeeTickets. “There’s the booking fee, the transaction fee and that’s it. Sometimes we don’t even charge a booking fee if we get inside commission, as we do on The Sound Of Music and Joseph, but that doesn’t happen in rock shows.”

Chris Edmonds at Ticketmaster adds, “the actual level of fees is not a huge issue to consumers, as long as they get a good experience and they know that when they’ve bought those tickets they will arrive in time for the event.”

Others, including proponents of mobile ticketing, however, note that many of the fees currently charged – notably postage and packing – vanish when the ticket is delivered digitally.

Ramesh Kumar of mobile ticketers Tixmob says “We have a ticket price and a booking fee, no extras, not even delivery fees, because we’re not posting anything.”

Today’s Ticketing Choices

Kumar’s point is timely, because the humble and once universal gig ticket is fast becoming an endangered species, as a raft of new approaches vie for the affections of the public.

The traditional, well-established agencies still deal in significant numbers of physical tickets, either posted out or collected at the venue, but recent technological advances have enabled appealing alternatives.

Print At Home, for example, offers ticket data e-mailed to the customer as a printable barcode, which is then scanned at the venue. “The public do seem to like print at home,” observes Nick Blackburn. “I think it’s a good technology but it requires scanners in the venues, and a lot of places can’t afford them.”

“I’m not a fan of print at home,” declares Mark Gasson of the Nottingham-based agency Gigantic. “It’s a barcode system, so what’s to prevent someone printing that e-mail out ten times and selling it on? Then the first person who turns up gets in, but nobody else.”

Like Tixmob, the Edinburgh-based Mobiqa has been finding significant acceptance for its mobile-phone-based alternative, the MobiTicket. “Our technology delivers a barcode by SMS to your mobile phone,” says Mobiqa Director Don Cameron, “It’s the same as on a print at home ticket, plus information about the artist, venue and time.”

Scanned at the venue directly from a phone’s screen, MobiTickets were used successfully as one option for the recent Ticketmaster/Live Nation gigs at Hyde Park.

It might surprise many to learn that innovative use of bargain basement digital technology is also benefiting some of the smallest venues on the live circuit. When Dave Newton, founder of Shifty Disco Records, set up a gig for The Unbelievable Truth at The Bull And Gate in Kentish Town in April 2000, he accidentally launched himself as a ticketing agency.

“I knew there were people who wanted to come from outside London for that gig but the ticket price was low, so mailing out tickets would have put the price up considerably,” he recalls. His solution was to use Shifty Disco’s online shop to e-mail tickets in the form of a numeric code which out-of-town fans brought to the gig where it was checked against a list.

Soon after, Newton realised his hastily-improvised system had greater potential. “Ticketmaster and SeeTickets were soaking up 95% of the tickets in the UK, but they start at a certain level,” he says. “Their pricing structure isn’t viable for tickets under £10. With booking fees and delivery charges and transaction charges, a £10 ticket ends up costing £16.”

Newton’s system has since blossomed with the addition of software which allows small gig promoters to log their gigs onto his site, wegottickets.com, thus selling tickets to customers they previously would not have reached. “We now have about 4,000 promoters registered with us, and our biggest single event so far was probably the 3000 tickets we sold for the 2008 Truck Festival.”

A similar idea lies at the heart of Matt McNeill’s Fulham-based company e-Tickets, which scooped the Innovative Business of The Year Award at the 2004 Natwest Startup Awards. “I couldn’t see why the existing agencies charged such high fees when so much of what they do is now automated,” he explains. McNeill’s system differs from wegottickets.com in that rather than a %, he charges promoters a flat rate per ticket sold. At the smaller venue level (up to 1000 capacity), promoters can choose his self-service option, but for larger events he tailors his service to match the needs of the client. “We’re now trading globally,” he reveals, “doing 12,000 tickets for the exit festival in Serbia and 20,000 for the Rhythm And Vines festival in New Zealand.” Is it any surprise he was named one of the top 10 business entrepreneurs to watch in the 2007 Courvoisier Future 500?

It’s not just the appearance and format of tickets that is changing. Many companies want to change the way the business thinks about tickets. Mark McLaughlin, co-founder of the Dublin-based Ticket-Text.com explains, “We are a low-cost mobile and e-ticket agency, but it’s not about the ticket. It’s about everything else you can do when you know more about your customers.”

For McLaughlin and others of like mind, the biggest advantage of a digitally delivered ticket is that the information collected along the way adds up to a database of knowledge about a venue’s customers which can be used to sell them other products and services.

New Kids On the Block

Alongside all of these technological innovations, the primary ticket market is also having to adapt to changes in its basic structure.

Potentially most significant of all, the dominance of agencies like Ticketmaster and SeeTickets in a booming live market will soon be challenged by the world’s largest promoter, Live Nation, which has opted to end its lengthy relationship with Ticketmaster and set up its own ticketing operation. Although Live Nation declined to comment on its plans for this feature, observers estimate that this move will make it the planet’s second biggest ticketing agency.

Ticketmaster’s Chris Edmonds, however, remains upbeat. “We’re very confident about Ticketmaster’s position in the market place, because we have a relationship with the consumer where they know they can come to us, they’ll be able to buy a ticket, they won’t get ripped off, and they’ll get good service.”

Another challenge to the ticket agency giants comes in the form of software developed by the Canadian company AudienceView, which is shaking things up at a number of major venue complexes around the UK. “AudienceView is about providing venues with control and an integrated suite of tools that is going to empower their business,” says Rob Edwards, VP Sales (Europe) of AudienceView Ticketing.

According to Edwards, as well as looking after transactions from low scale high volume, the software is capable of handling CRM (customer relationship management), marketing, data mining to inform marketing campaigns, fund-raising and membership subscriptions.

One evidently happy AudienceView customer is the NEC, which used the software to launch its own Ticket Factory last October. General Manager Saad Afzal says, “We knew that by leveraging our technology investment to become an independent, national ticket agent whilst retaining the customer-service ethos and ‘big-picture’ understanding of a venue box office, we could offer promoters and organisers a truly unique and compelling proposition.”

The NEC is not alone. AudienceView has also ‘empowered’ Sheffield Arena and the Liverpool Echo Arena. “The power of Ticketmaster And See is being challenged by a range of new entrants into the market,” says Saad Afzal, “ranging from small ticket brokers with website-only operations up to Live Nation.”

Smaller operations too are seeking to compete with the big boys in novel ways. Nottingham’s Gigantic, for example, are combining green virtues (they donate 10% of their booking fees to Oxfam) with a ‘small is beautiful’ ethic. “If you go onto Ticketmaster or SeeTickets on a Friday morning,” states MD Mark Gasson, “both sites are maxxed out, you can’t get through. We have pretty much the same tickets but, because we’re still the new guys, people can get onto us quickly.”

Another unexpected development has been the recent alliance of booking agency Primary Talent with SeeTickets. “It’s about empowering our artists with self-marketing tools,” explains MD Peter Elliott. Via their newly-established ArtistTicket.co.uk, Primary Talent’s artists now receive an allocation of tickets to sell through their own websites, with booking fees split between all three parties to the deal but, stresses Elliott, “The real heart of what this is about is the data which can help artists sell other products as well as tickets.”

Secondary ticketing

If any single issue has riven the live music industry it’s secondary ticketing.

“It is destroying the business….” insists Peter Elliott at Primary Talent, while Nick Blackburn at SeeTickets states, “I loathe it. It’s simply another word for touting.”

Eric Baker, founder of Viagogo, disagrees. “People have been re-selling tickets since the beginning of time,” he says. “I’m sure they re-sold tickets to Shakespeare’s plays. All we’re doing is making that transaction safe, secure and efficient.”

Just months ago, secondary ticketers like Viagogo, Seatwave and Get Me In were almost universally decried as little more than high tech ticket touts. They argued, however, that their sites had introduced stability and security into a market which, in its previous incarnation on eBay, was completely unregulated.

“The secondary ticketing market was one in which lots of people were spending lots of money,” says Seatwave founder Joe Cohen, “but the consumer experience was terrible. I felt we could build a service to provide a better consumer experience and bring prices down.”

Efforts to make the government pass legislation to control secondary ticketing – a market reckoned by sector analysts Tixdaq.com to be worth £200m a year – floundered.

With vast sums evidently at stake, some major players opted for pragmatic solutions. In January 2008 Ticketmaster bought Get Me In for a sum reportedly a little under £50m. In May, Madonna and Live Nation struck a deal with Viagogo who agreed to pay them a rights fee in return for becoming Madge’s official premium seat and secondary ticketer. In July, Seatwave became the official ticket re-saler for Grand Union Management.

These and other developments were perceived by many as legitimising secondary ticketing, and fears that such liaisons would push prices up were bolstered when the Tixdaq price comparison site reported that while £75 Madonna tickets were still available from Ticketmaster, identical tickets were being offered at up to £196 each by Viagogo.

Nevertheless, Andrew Blachman, CEO of Get Me In, is confident that, “Things are changing in our direction. Five years ago in the US a lot of people didn’t like secondary ticketing but now you’d be hard pressed to find a team or a league or an artist that isn’t participating in the secondary market. It took a while to happen over there but it seems to be happening a little faster here.”

There are, however, still many who feel that embracing secondary ticketing is a short-term solution at best, which will ultimately do more damage than good.

“You know, there is money to be made out of ticket re-sales in a legitimate way,” suggests Peter Elliott of Primary Talent. “Customers should be able to sell unwanted tickets back to the ticket agents who can re-sell it, or create some sort of ticket exchange, without a mark up. But the over-pricing, the middle man who doubles the ticket cost, that’s what’s killing the business.”