Fact #118304

When:

Short story:

People Got To Be Free by The Rascals tops the Billboard Singles Chart in the USA for the first of five weeks.

People Got To Be Free by The Rascals tops the Billboard Singles Chart in the USA for the first of five weeks.Full article:

"Atlantic Records didn't want to put People Got To Be Free out," remembers Gene Cornish, guitarist for The Rascals. "They said, You're going to kill your pop base."

Cornish's memory is corroborated by drummer Dino Danelli. "Atlantic said it was too political and that it went against the grain. They didn't want to release it, but we stuck to our guns, and it turned out to be the biggest record we ever had." The company really should have known better. After all, The Rascals' entire history with the label up to that point had been one of group instincts confounding received corporate wisdom.

Formed as The Rascals in 1964 by disenchanted members of Joey Dee And The Starliterswho felt it was not unreasonable to get cash as well as glory for playing music, the Long Island-based blue-eyed soul quartet were soon the hottest live act on the club circuit. Within a year they were sitting round a table in The Barge, a floating niterie in the expensive Westhampton distict, savouring the sight of Atlantic Records supremo Ahmet Ertegun vying for their favours against Phil Spector. As Ertegun's partner Jerry Wexler remembers, "With his European charm, his war stories of the R'n'B fifties, his ability to do the white-boy dozens, his put-downs, his praises, his accomplishments, his eclecticism, his hedonism - Ahmet wiped Spector out." More significantly, Ertegun offered the group total creative control, something Spector would never countenance.

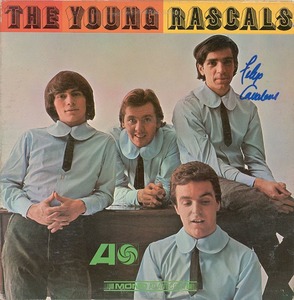

Almost from the start, though, Ertegun's ploy ran Atlantic into problems. Re-named The Young Rascals at Atlantic's suggestion, the group sounded very black and recorded for a predominantly black label so, when their first single went out in a plain sleeve, as producer Tom Dowd recalls, "Everybody thought we were repeating what we'd done previously but they didn't realise it was a white group."

Exercising their option, the band insisted that their second single, Good Lovin', was issued in a picture sleeve, and the jig was up. "All of a sudden we had very stiff resistance in one or two parts of the United States," says Dowd. "When they saw the cover, they didn't like them any more." Nevertheless, Good Lovin' went on to become a US No1 hit in 1966.

Come 1967, having established themselves with a string of soulful smashes, The Young Rascals did a volte-face with Groovin', an ethereally laid-back Afro-Cuban-inflected slowie, that once again put Atlantic into a spin. "They didn't like it at all," observes Felix Cavaliere, whose Hammond organ grooves had always been at the heart of the group. "They didn't want to put it out. They said, Look, you're known as a rockin' band, known for this Good Lovin' kind of white soul. What the heck are you gonna do now? You gonna become little sweethearts?" Fortunately, total creative control meant that the group could over-ride corporate anxieties, and Groovin' earned them another No1.

The group threw the company two more curve balls in 1968 when they decided first to shorten the name back to The Rascals and, even more controversially, to make an overtly political statement on their next single, People Got To Be Free. Cavaliere had been shocked, first by the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King, and then by Robert Kennedy's murder. "We were kind of involved with the Kennedys. We worked with them, and it just really wrecked me. I remember it vividly. The first thing I wanted to do was attack something or somebody. But it changed me. It really did. And People Got To Be Free came as a result."

By this point, arguably, Atlantic should have learned to trust the group's instincts but once again, they tried to block the single. As Gene Cornish recalls, "We said, We're not talking about just blacks, we're talking about religion, we're talking about art, freedom of speech, and freedom to put this freakin' record out. And we happen to have the last say in our contract."

As Atlantic predicted, People Got To Be Free attracted a right-wing backlash. "We're really knocked out," responded Cavaliere, "that three minutes of music can create so much discussion and mess up so many straights." The song Atlantic didn't want to release went on to sell 4.5m copies and topped the American charts from 17 August 1968 for a total of five weeks.

Tweet this Fact

Cornish's memory is corroborated by drummer Dino Danelli. "Atlantic said it was too political and that it went against the grain. They didn't want to release it, but we stuck to our guns, and it turned out to be the biggest record we ever had." The company really should have known better. After all, The Rascals' entire history with the label up to that point had been one of group instincts confounding received corporate wisdom.

Formed as The Rascals in 1964 by disenchanted members of Joey Dee And The Starliterswho felt it was not unreasonable to get cash as well as glory for playing music, the Long Island-based blue-eyed soul quartet were soon the hottest live act on the club circuit. Within a year they were sitting round a table in The Barge, a floating niterie in the expensive Westhampton distict, savouring the sight of Atlantic Records supremo Ahmet Ertegun vying for their favours against Phil Spector. As Ertegun's partner Jerry Wexler remembers, "With his European charm, his war stories of the R'n'B fifties, his ability to do the white-boy dozens, his put-downs, his praises, his accomplishments, his eclecticism, his hedonism - Ahmet wiped Spector out." More significantly, Ertegun offered the group total creative control, something Spector would never countenance.

Almost from the start, though, Ertegun's ploy ran Atlantic into problems. Re-named The Young Rascals at Atlantic's suggestion, the group sounded very black and recorded for a predominantly black label so, when their first single went out in a plain sleeve, as producer Tom Dowd recalls, "Everybody thought we were repeating what we'd done previously but they didn't realise it was a white group."

Exercising their option, the band insisted that their second single, Good Lovin', was issued in a picture sleeve, and the jig was up. "All of a sudden we had very stiff resistance in one or two parts of the United States," says Dowd. "When they saw the cover, they didn't like them any more." Nevertheless, Good Lovin' went on to become a US No1 hit in 1966.

Come 1967, having established themselves with a string of soulful smashes, The Young Rascals did a volte-face with Groovin', an ethereally laid-back Afro-Cuban-inflected slowie, that once again put Atlantic into a spin. "They didn't like it at all," observes Felix Cavaliere, whose Hammond organ grooves had always been at the heart of the group. "They didn't want to put it out. They said, Look, you're known as a rockin' band, known for this Good Lovin' kind of white soul. What the heck are you gonna do now? You gonna become little sweethearts?" Fortunately, total creative control meant that the group could over-ride corporate anxieties, and Groovin' earned them another No1.

The group threw the company two more curve balls in 1968 when they decided first to shorten the name back to The Rascals and, even more controversially, to make an overtly political statement on their next single, People Got To Be Free. Cavaliere had been shocked, first by the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King, and then by Robert Kennedy's murder. "We were kind of involved with the Kennedys. We worked with them, and it just really wrecked me. I remember it vividly. The first thing I wanted to do was attack something or somebody. But it changed me. It really did. And People Got To Be Free came as a result."

By this point, arguably, Atlantic should have learned to trust the group's instincts but once again, they tried to block the single. As Gene Cornish recalls, "We said, We're not talking about just blacks, we're talking about religion, we're talking about art, freedom of speech, and freedom to put this freakin' record out. And we happen to have the last say in our contract."

As Atlantic predicted, People Got To Be Free attracted a right-wing backlash. "We're really knocked out," responded Cavaliere, "that three minutes of music can create so much discussion and mess up so many straights." The song Atlantic didn't want to release went on to sell 4.5m copies and topped the American charts from 17 August 1968 for a total of five weeks.