Fact #113805

When:

Short story:

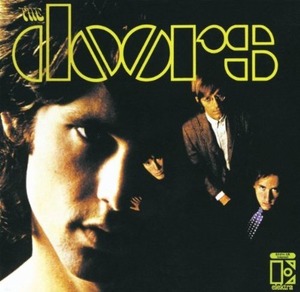

The Doors release their eponymous debut album, and their debut single, Break On Through, on Elektra Records in the USA.

The Doors release their eponymous debut album, and their debut single, Break On Through, on Elektra Records in the USA.Full article:

Although an instant critical smash, The Doors' debut didn't register on UK charts until 1991 when, propelled by Oliver Stone's biopic, it struggled to No43. Back in 1967, though, the jolt wasn't just Morrison's intimidating, oedipal and surreal lyrics, exploring areas never before touched by rock writers. Much of the power came from the exotic blending of Ray Manzarek's keyboards, shaded by New Orleans stride and classical influences, duetting with Robbie Krieger's swooping fretwork, sometimes bluesy, sometimes evoking Indian ragas, while drummer John Densmore used every percussion trick in the book to illustrate Morrison's stories without ever skipping a beat. Perhaps more significantly, before The Doors, a slow song was almost invariably a romantic ballad. After The Doors, anything was possible.

Jac Holzman (owner, Elektra Records) : Paul Rothchild was always my choice to make that record, to work with that band. Paul, at first, didn't want to do it. There was a band that he saw in New York called The Paupers that he was more interested in. I finally just kind of pushed him into it and said, "You've got to do this." He agreed and he tackled it with the usual Rothchild energy which was total. I also thought he'd be the only guy able to stand up to every member of the band, either individually or collectively. I also thought that they had done a lot of wood-shedding but their music wasn't organized for a record yet. And that Paul was the right person to help them give it shape but it had to be done skilfully. He was a terrific technician in the studio and backing him up with Botnick. . . Botnick was my favourite engineer for this kind of stuff and Bruce and I had worked together on Love. So I thought that was the right combination and I insisted that it be that way. It worked out brilliantly.

Robby Krieger (guitarist, The Doors] : On our first album with Paul Rothchild, Jim was so strung out on acid when we were trying to do The End that he got totally out of hand. He threw a tv set through the control-room window, and he was into this Oedipus-complex trip and saying, 'Fuck the mother. Kill the father' and he would just rant on like that for hours. When we finally managed to get him in to record the song, he started doing it great.

Then we decided he was too high to continue, so we closed the session. But by now Jim didn't want to stop, so he climbed back into the place and started having fun by hosing down the place with a fire extinguisher, including all the instruments. Paul jumped in and dragged him out.

Jac Holzman : When the record was finished and mastered, which was October 1966, I had told them that we'd release the record in November. I began to get cold feet because I was worried about certain records that were coming out toward the end of the year that might take away from the impact I wanted The Doors to make, and also Christmas records had a longer season than they do now. So I was concerned about that. And also the boys wanted it out. I sat down with them and said, "Look guys, let's come out in January. January 4th when nobody's going to come out with a record. I won't release any other album that month so you have a clear shot." And that's what we did. That was an immensely important decision and concession on their part.

Everybody at the company - people in the business affairs department kept everything going smoothly in our relationship with the band. We had a sense of what we were doing. We had a plan. I wrote every one of our 32 independent distributors that we had at the time in 1967. I said, "This is the best thing we've ever had and we need everybody's help on this one. This is it for us." And it turned out to be true. We had no hint that this thing was going to explode the way it did. It sold 10,000 a month for the first two or three months which was not an insignificant number of records and then it jumped to 250,000. I would say everybody within the label was important. The distributors caught that we really believed in this and gave some extra special help, so that was important. Jac Holzman : I've been faulted for releasing that single (Break On Through) first. In the context of its day and at the time it was the right thing to do because if we were going to learn our way we were not going to learn our way on Light My Fire, rather with Break On Through and get the marketplace prepared. It was just too early to start with Light My Fire. Break On Through was a good tune for that, and we made a video for it. There is a film on that which we shot using our own camera with our own people, in-house, with an optical as well as a magnetic soundtrack, which was sent out to the various TV stations that ran dance shows. Elektra was independent without a lot of money and we couldn't afford necessarily to tour the band, but what we could afford to do was send this "video" out. And it worked. We sent out a lot of them.

The success of The Doors gave Elektra a very special kind of visibility from which we were able to get other artists as a result. It was one of the luckiest times of my life. I rode the tiger. I spent as much energy hanging on as I did enjoying it. I wish I had enjoyed it more. It was tough.

Jac Holzman (founder, Elektra Records) : With the Doors, I had arrived in Los Angeles one very late night, and went to see Love. Arthur said, “You ought to stick around to see the band that’s opening.” I didn’t hear anything, but if Arthur said there was something here, I would keep going, and on the fourth night I found it. They hadn’t done “Light My Fire,” or any of their classic repertoire; it was still a lot of leftover Rick & the Ravens material. But on the fourth night, they did “The Alabama Song,” and it was like the Rosetta Stone. I went back and introduced myself to them. They knew of Elektra, and were kind of amused that this folk label was getting into rock ‘n ‘roll, but we had sold almost 150,000 Love albums and that impressed them, and I was very persistent. I looked at their experience with Columbia, which had kept them on a string for six months, and I concluded that they needed a guarantee we would release records. And that’s what I gave them: a six-album contract with the stipulation that we would release at least four; no label gave that to an artist in those days. I was willing to suspend my option of keeping their albums on a shelf, because I knew one thing: I had already heard two albums of great material.

We released the first album on January 4, 1967, and Strange Days nine month later.

(Source : Interview by Lenny Kaye at http://www.wonderingsound.com/interview/elektra-records-founder-jac-holzman/)

Bruce Botnick (engineer) : I was the engineer, I recorded it. But in any good relationship between artist, producer, and engineer, there is a meeting of the minds, and a lot of it is unspoken. It's an understanding and there's a chemistry there. There was nobody that said, "You're the producer, or you're the engineer." It was a team effort. You didn't think about these things; it' s just the way it was, nobody felt threatened. Any good producer tries to extract performances and not put his or her viewpoint into the fore. My name on the cover of the album is not going to sell the album; the artist is going to sell the album.

(Source : interview by Matthew Greenwald, Analog Planet, May 1, 2010)

----------------------------------------------------------

THE DOORS DEBUT LP

by Johnny Black

The Doors debut album broke new ground by fusing elements of theatre, poetry and psychology into a hard rock format.

Recorded over six days in August 1966 at Sunset Sound, Los Angeles, much of its impact came from the exotic blending of Ray Manzarek’s keyboards, shaded by New Orleans stride and classical influences, duetting with Robbie Krieger’s swooping fretwork, sometimes bluesy, sometimes evoking Indian ragas, while drummer John Densmore employed every percussion trick in the book to illustrate Jim Morrison’s story-songs without ever skipping a beat. The real jolt, however, was Morrison’s intimidating, oedipal and surreal lyrics, exploring areas formerly taboo, even in rock.

Light My Fire, the Krieger-composed hit single, gave the band superstar status, but the key track was The End, which had been recorded by the light of a single candle. This brooding, hallucinatory, gothic nightmare set to music, was wholly new in its musical structure and lyrics.

In a world where the most outrageous of mainstream rock bands could achieve notoriety simply by turning their amps up or introducing sexual or socio-political themes into their lyrics, The Doors music was remarkably sophisticated and Morrison’s lyrics, probing the murkier depths of the human psyche, were downright shocking.

ELEKTRA RECORDS

In the mid-60s, Elektra Records radically expanded the horizons of rock by insisting on excellence and innovation in every aspect of its operations.

Company founder Jac Holzman, a college student at St John’s, Annapolis, Maryland, had more interest in electronics, radio and tape recorders than in his scheduled classes. Inspired by a classical concert, Holzman decided to start his own record company and on October 10, 1950, he named it Elektra Records.

Elektra’s first release, New Songs by contemporary classical composer John Gruen, was a commercial disaster. Holzman re-located to Greenwich Village, opened a record store to generate cash, and recorded a second album, the memorably titled Jean Ritchie Singing The Traditional Songs Of Her Kentucky Mountain Family. This garnered critical acclaim and sold enough copies to put Elektra on a firmer footing.

Adding blues to its folk-based catalogue in 1954, Elektra moved to bigger offices. Always politically-active, Holzman boldly signed Josh White to Elektra when his former label, Decca, dumped him because he had been placed on Sen. Joe McCarthy’s Communist Witch Hunt black list.

The early 60s folk boom boosted Elektra’s fortunes and Holzman’s earlier reservations about rock music were swept away on July 25, 1965, when he watched Bob Dylan go electric at Newport Folk Festival. “Dylan and folk music and Elektra were never the same again,” he has said.

Determined to get behind the new, politically aware, intellectually challenging form of rock that was emerging, Holzman first signed Los Angeles-based Love ("Five guys of all colours, black, white and psychedelic - that was a real first. My heart skipped a beat. I had found my band!") and then The Doors.

Suddenly, without compromising its principles, little Elektra was scoring hit singles and competing in the same arena as giants like Columbia, Capitol and RCA. Entering its golden age, Elektra signed a string of ground-breaking acts, each of which explored the outer fringes of rock. To name just three, The Holy Modal Rounders invented psychedelic folk; Ars Nova took the combination of baroque and rock to its logical conclusion; and The Stooges were hammering out punk rock five years too soon.

The label’s big blocky ‘E’ logo became a hallmark of quality, not just for Elektra’s choice of artists but for exquisite sound reproduction and imaginative sleeve designs. Holzman’s unswerving commitment to quality also meant that when album sales began to overtake singles in the late sixties, his label was perfectly placed to reap the benefits because knocking off quick hits had never been a feature of Elektra’s recording policy.

Throughout this period, Elektra also continued to record cutting edge folk artists, including Tim Buckley, Phil Ochs and the Holy Modal Rounders, while its classically-oriented sister label, Nonesuch, scored a totally unexpected international smash with Joshua Rifkin’s recordings of piano rags by Scott Joplin.

By the start of the 70s, however, Holzman, was wearying of the business and moved to Hawaii. Elektra was merged, first with David Geffen’s Asylum Records, then with Warner Bros, thus forming WEA (Warner/Elektra/Asylum). Under new management, the label continued to sign quality artists, and achieved higher sales figures than ever, but the Holzman fingerprint was gone and Elektra’s unique identity was lost forever.

(Source : by Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums by Backbeat Books, 2007)

Tweet this Fact

Jac Holzman (owner, Elektra Records) : Paul Rothchild was always my choice to make that record, to work with that band. Paul, at first, didn't want to do it. There was a band that he saw in New York called The Paupers that he was more interested in. I finally just kind of pushed him into it and said, "You've got to do this." He agreed and he tackled it with the usual Rothchild energy which was total. I also thought he'd be the only guy able to stand up to every member of the band, either individually or collectively. I also thought that they had done a lot of wood-shedding but their music wasn't organized for a record yet. And that Paul was the right person to help them give it shape but it had to be done skilfully. He was a terrific technician in the studio and backing him up with Botnick. . . Botnick was my favourite engineer for this kind of stuff and Bruce and I had worked together on Love. So I thought that was the right combination and I insisted that it be that way. It worked out brilliantly.

Robby Krieger (guitarist, The Doors] : On our first album with Paul Rothchild, Jim was so strung out on acid when we were trying to do The End that he got totally out of hand. He threw a tv set through the control-room window, and he was into this Oedipus-complex trip and saying, 'Fuck the mother. Kill the father' and he would just rant on like that for hours. When we finally managed to get him in to record the song, he started doing it great.

Then we decided he was too high to continue, so we closed the session. But by now Jim didn't want to stop, so he climbed back into the place and started having fun by hosing down the place with a fire extinguisher, including all the instruments. Paul jumped in and dragged him out.

Jac Holzman : When the record was finished and mastered, which was October 1966, I had told them that we'd release the record in November. I began to get cold feet because I was worried about certain records that were coming out toward the end of the year that might take away from the impact I wanted The Doors to make, and also Christmas records had a longer season than they do now. So I was concerned about that. And also the boys wanted it out. I sat down with them and said, "Look guys, let's come out in January. January 4th when nobody's going to come out with a record. I won't release any other album that month so you have a clear shot." And that's what we did. That was an immensely important decision and concession on their part.

Everybody at the company - people in the business affairs department kept everything going smoothly in our relationship with the band. We had a sense of what we were doing. We had a plan. I wrote every one of our 32 independent distributors that we had at the time in 1967. I said, "This is the best thing we've ever had and we need everybody's help on this one. This is it for us." And it turned out to be true. We had no hint that this thing was going to explode the way it did. It sold 10,000 a month for the first two or three months which was not an insignificant number of records and then it jumped to 250,000. I would say everybody within the label was important. The distributors caught that we really believed in this and gave some extra special help, so that was important. Jac Holzman : I've been faulted for releasing that single (Break On Through) first. In the context of its day and at the time it was the right thing to do because if we were going to learn our way we were not going to learn our way on Light My Fire, rather with Break On Through and get the marketplace prepared. It was just too early to start with Light My Fire. Break On Through was a good tune for that, and we made a video for it. There is a film on that which we shot using our own camera with our own people, in-house, with an optical as well as a magnetic soundtrack, which was sent out to the various TV stations that ran dance shows. Elektra was independent without a lot of money and we couldn't afford necessarily to tour the band, but what we could afford to do was send this "video" out. And it worked. We sent out a lot of them.

The success of The Doors gave Elektra a very special kind of visibility from which we were able to get other artists as a result. It was one of the luckiest times of my life. I rode the tiger. I spent as much energy hanging on as I did enjoying it. I wish I had enjoyed it more. It was tough.

Jac Holzman (founder, Elektra Records) : With the Doors, I had arrived in Los Angeles one very late night, and went to see Love. Arthur said, “You ought to stick around to see the band that’s opening.” I didn’t hear anything, but if Arthur said there was something here, I would keep going, and on the fourth night I found it. They hadn’t done “Light My Fire,” or any of their classic repertoire; it was still a lot of leftover Rick & the Ravens material. But on the fourth night, they did “The Alabama Song,” and it was like the Rosetta Stone. I went back and introduced myself to them. They knew of Elektra, and were kind of amused that this folk label was getting into rock ‘n ‘roll, but we had sold almost 150,000 Love albums and that impressed them, and I was very persistent. I looked at their experience with Columbia, which had kept them on a string for six months, and I concluded that they needed a guarantee we would release records. And that’s what I gave them: a six-album contract with the stipulation that we would release at least four; no label gave that to an artist in those days. I was willing to suspend my option of keeping their albums on a shelf, because I knew one thing: I had already heard two albums of great material.

We released the first album on January 4, 1967, and Strange Days nine month later.

(Source : Interview by Lenny Kaye at http://www.wonderingsound.com/interview/elektra-records-founder-jac-holzman/)

Bruce Botnick (engineer) : I was the engineer, I recorded it. But in any good relationship between artist, producer, and engineer, there is a meeting of the minds, and a lot of it is unspoken. It's an understanding and there's a chemistry there. There was nobody that said, "You're the producer, or you're the engineer." It was a team effort. You didn't think about these things; it' s just the way it was, nobody felt threatened. Any good producer tries to extract performances and not put his or her viewpoint into the fore. My name on the cover of the album is not going to sell the album; the artist is going to sell the album.

(Source : interview by Matthew Greenwald, Analog Planet, May 1, 2010)

----------------------------------------------------------

THE DOORS DEBUT LP

by Johnny Black

The Doors debut album broke new ground by fusing elements of theatre, poetry and psychology into a hard rock format.

Recorded over six days in August 1966 at Sunset Sound, Los Angeles, much of its impact came from the exotic blending of Ray Manzarek’s keyboards, shaded by New Orleans stride and classical influences, duetting with Robbie Krieger’s swooping fretwork, sometimes bluesy, sometimes evoking Indian ragas, while drummer John Densmore employed every percussion trick in the book to illustrate Jim Morrison’s story-songs without ever skipping a beat. The real jolt, however, was Morrison’s intimidating, oedipal and surreal lyrics, exploring areas formerly taboo, even in rock.

Light My Fire, the Krieger-composed hit single, gave the band superstar status, but the key track was The End, which had been recorded by the light of a single candle. This brooding, hallucinatory, gothic nightmare set to music, was wholly new in its musical structure and lyrics.

In a world where the most outrageous of mainstream rock bands could achieve notoriety simply by turning their amps up or introducing sexual or socio-political themes into their lyrics, The Doors music was remarkably sophisticated and Morrison’s lyrics, probing the murkier depths of the human psyche, were downright shocking.

ELEKTRA RECORDS

In the mid-60s, Elektra Records radically expanded the horizons of rock by insisting on excellence and innovation in every aspect of its operations.

Company founder Jac Holzman, a college student at St John’s, Annapolis, Maryland, had more interest in electronics, radio and tape recorders than in his scheduled classes. Inspired by a classical concert, Holzman decided to start his own record company and on October 10, 1950, he named it Elektra Records.

Elektra’s first release, New Songs by contemporary classical composer John Gruen, was a commercial disaster. Holzman re-located to Greenwich Village, opened a record store to generate cash, and recorded a second album, the memorably titled Jean Ritchie Singing The Traditional Songs Of Her Kentucky Mountain Family. This garnered critical acclaim and sold enough copies to put Elektra on a firmer footing.

Adding blues to its folk-based catalogue in 1954, Elektra moved to bigger offices. Always politically-active, Holzman boldly signed Josh White to Elektra when his former label, Decca, dumped him because he had been placed on Sen. Joe McCarthy’s Communist Witch Hunt black list.

The early 60s folk boom boosted Elektra’s fortunes and Holzman’s earlier reservations about rock music were swept away on July 25, 1965, when he watched Bob Dylan go electric at Newport Folk Festival. “Dylan and folk music and Elektra were never the same again,” he has said.

Determined to get behind the new, politically aware, intellectually challenging form of rock that was emerging, Holzman first signed Los Angeles-based Love ("Five guys of all colours, black, white and psychedelic - that was a real first. My heart skipped a beat. I had found my band!") and then The Doors.

Suddenly, without compromising its principles, little Elektra was scoring hit singles and competing in the same arena as giants like Columbia, Capitol and RCA. Entering its golden age, Elektra signed a string of ground-breaking acts, each of which explored the outer fringes of rock. To name just three, The Holy Modal Rounders invented psychedelic folk; Ars Nova took the combination of baroque and rock to its logical conclusion; and The Stooges were hammering out punk rock five years too soon.

The label’s big blocky ‘E’ logo became a hallmark of quality, not just for Elektra’s choice of artists but for exquisite sound reproduction and imaginative sleeve designs. Holzman’s unswerving commitment to quality also meant that when album sales began to overtake singles in the late sixties, his label was perfectly placed to reap the benefits because knocking off quick hits had never been a feature of Elektra’s recording policy.

Throughout this period, Elektra also continued to record cutting edge folk artists, including Tim Buckley, Phil Ochs and the Holy Modal Rounders, while its classically-oriented sister label, Nonesuch, scored a totally unexpected international smash with Joshua Rifkin’s recordings of piano rags by Scott Joplin.

By the start of the 70s, however, Holzman, was wearying of the business and moved to Hawaii. Elektra was merged, first with David Geffen’s Asylum Records, then with Warner Bros, thus forming WEA (Warner/Elektra/Asylum). Under new management, the label continued to sign quality artists, and achieved higher sales figures than ever, but the Holzman fingerprint was gone and Elektra’s unique identity was lost forever.

(Source : by Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums by Backbeat Books, 2007)