Fact #77843

When:

Short story:

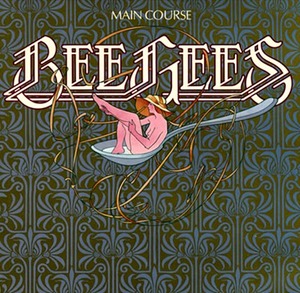

The Bee Gees arrive at 461 Ocean Boulevard, Golden Beach, Miami, Florida, USA, to begin work at the nearby Criteria Studios, on a new album which will be called Main Course.

The Bee Gees arrive at 461 Ocean Boulevard, Golden Beach, Miami, Florida, USA, to begin work at the nearby Criteria Studios, on a new album which will be called Main Course.Full article:

Robin Gibb : We were in a real dead zone. No-one wanted to hear us. The record company wasn't interested.

Barry Gibb : We got into pills - Dexedrine - and liquor too. The only thing that we never got involved with was LSD.

Maurice Gibb : Part of the problem was that our manager, Robert Stigwood, had become so involved with stage shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and movies, that he'd taken his eye off us, and we were kind of drifting.

Barry Gibb : We ended up in Batley Variety Club. It was a little club up north and, if you ended up working there it can be safely said that you're not required anywhere else. In those days, that was the place not to work in, and we ended up working there.

I remember us talking about it backstage at that place and I said, 'If this is the bottom, there's no further we can fall. Something's gotta happen for the positive.'

Blue Weaver (keyboards) : The Bee Gees drummer then was Dennis Byron who'd been in Amen Corner with me years before, and he rang me up to ask if I'd be interested in joining the band. They'd realised they had to change direction, and they were trying to inject some fresh ideas into the band. In December of 1974 I had a meeting with them where they lived, in the Isle Of Man.

I went over and stayed with Barry for the weekend - went over on Friday night and came back on the Sunday night. As I'm leaving, I'm walking out the door, and Barry says, 'Here! I haven't heard you play piano yet!' I was actually putting my bags in the car, and I said, 'Oh, do you have a piano?' They had this old thing in the back - it was all out of tune … I rattled out a quick tune on the piano and they said, 'Fine, can you come to Miami next month?' So I agreed to start work with them at Criteria Studios on January 2, because that had been recommended to them by Eric Clapton…

Barry Gibb : We had a conversation with Eric Clapton about making a comeback because he was trying to make a comeback, and we were always trying to make a comeback. Eric said, 'I've just made this album called 461 Ocean Boulevard in Miami. Why don't you guys go to America and do the same and maybe the change of environment will do something for you?' I think it was really good advice...

Blue Weaver : We all moved into 461 on Golden Beach, and started writing material there. Basically we'd lie all day on the beach, then work over at the studio in the evening, and late into the night.

When I joined, I think it was the lowest ebb that the three brothers had been. I'd actually heard Mr. Natural as well, and I thought that was great, and there were elements in that that I obviously felt we could take further.

I got a little bit worried at first...we all have personal problems, but sometimes the personal problems overrun into-well, we were all living in one house so there was no way that you could hide anything that goes on. If one person drinks a little too much, everybody else is gonna know about it.

There were a few things to overcome, and obviously politics as well, if you're going to change something. If Maurice, for instance, had been playing the piano, and suddenly you decide that I'm going to play the piano or something like that, then you have to be a little diplomatic and break things in gently. As soon as they could see the potential, as soon as we started doing things, there was no problem.

Maurice Gibb : The drink and drugs didn't stop when we went to Miami. We were known affectionately throughout the music business as Pilly, Potty and Pissy, because I was the piss artist, Barry was the pot-head and Robin was the pill-head, but we were determined to change, and we asked for Arif Mardin of Atlantic Records as producer, because we'd had a good experience working with him on the previous album, Mr Natural.

Barry Gibb : Quite simply, [Arif is] the best producer in the world for us. In that studio with him is magic. There isn't any certain kind of technique or attitude that he uses. He's totally like an uncle. He rolls in there with you. As far as a song is concerned, you take it to him. He says the song is fantastic; however, put that verse there, that chorus there. He's that kind of producer - doesn't take the song away from you, he just places it where he thinks it should be. He brought it out of us again. We knew we couldn't go in there and make another album that wasn't going to go.

Robin Gibb : Our roots was the R'n'B music, but we didn't know what direction would be best to go in. So Main Course was several directions, country with songs like Come On Over, and R'n'B with songs like Nights On Broadway and Jive Talkin'.

Maurice Gibb : The house engineer at Criteria when we arrived was a guy called Karl Richardson. Karl knew this other guy, Albhy Galuten who had worked with Clapton and such. The first time I saw him he was barefoot, eating his bloody grease tree [avocado] sandwiches, and he looked quite alarming. I was a bit frightened by him. He was a keyboard player who had his own studio and did a few things. He didn’t work on Main Course, but he became part of the team on the later albums.

Arif Mardin (producer) : We started to record, and some of the songs were still in their old ballad style.

Linda Gibb (wife of Barry Gibb) :They were in the studio putting some tracks down. Dick [Ashby] and Tom [Kennedy] and I were the onlookers, and we were looking at each other and thinking, 'This isn't what's happening now. They've got to write something more up-tempo.'

Ahmet Ertegun (MD, Atlantic Records) : After Arif took over, they went over into a whole new RAndB direction, and disco... Arif did a lot for the group. And they did a lot for Arif. That was one of Arif's great successes in his career.

Blue Weaver : Although the brief, from the start, was to find a new direction, the first songs we worked on, Was It All In Vain and Our Love Will Save The World, were actually in the same old Bee Gees ballad style, and when their manager Robert Stigwood heard the tapes we sent him, he wasn't impressed.

The first song that we all realised that that we'd hit on something that was going to develop was Wind Of Change. I knew that we were going to come away with a hit album no matter what - I mean, we all did, I think. It was just finding out direction... I mean, nobody had any doubts about things not happening.

Barry Gibb : One of the first four songs we came up with and played to Arif was Wind Of Change. He took those songs to Atlantic and played them, and they didn't like them.

Robin Gibb : Ahmet was so quick to turn off to us, to say, 'This is it?' We thought they weren't even going to give us a chance. They were burying us. Only Arif, of all the Atlantic people, kept faith in us.

Barry Gibb : Atlantic wasn't at all prepared to go that way because we hadn't had successful albums for about four or five years.

Maurice Gibb : Stigwood and Ahmet Ertegun flew down, and told us they didn't like the songs. We were devastated, but Stigwood sat on Golden Beach with us and apologised for having been so distant from us, and said, 'I'm determined to get involved again.'

Robert Stigwood (manager, Bee Gees) : I didn't like a lot of the tracks. I flew down to Miami and told them I wanted to scrap a lot of the things they'd done, and I'd like them to start again. I would swallow the costs, not to worry, but to really open their ears and find out in contemporary terms what is going on.

Barry Gibb : We had been writing about politics and saving the world for so many years, and we decided that we would try something light-hearted, and we did. We didn't cunningly go into the disco market to gain greater strength in the record market, as some people implied at the time. We simply tried to embrace all kinds of music, whatever music there was.

It was more about getting back into the music we were always into, which was RAndB. When we arrived in Florida, the place teemed with it. Here was a new culture to absorb, to base our music on. That's basically what we've done all our lives. Everything sprang from our deep love of RAndB - Al Green, Otis Redding, the Stylistics.

So we went to work with Arif, and he said, 'I'm going away for a week and I want you to write while I'm away. During the week he was away, we wrote Jive Talkin', Nights On Broadway, Edge Of The Universe. All those songs we wrote in one week, simple because we knew that this was it. If this album doesn't work, it's the finish for our recording career.

Blue Weaver : During Main Course, the sound changed so drastically because synthesisers were used, and technology was introduced rather than just an orchestra and a piano. That was a change as well. There hasn't been musically much change since then because nothing new has been invented to make such a tremendous difference to the sound as the synthesiser did, compared to an orchestra.

Arif Mardin : We would try many things, like synthesisers … At that time, I think Stevie Wonder was using synthesiser bass. Only certain people were using synthesisers, and Stevie was one of them. I used to use synthesiser too, before we recorded them but, at that time, they were very primitive. They were monophonic. If you wanted to play a chord, the guy had to play three notes, three times, and stack the harmonies up.

Robin Gibb : The actual track that started it all off was Jive Talkin'. That snowballed one night and the energy went on for a couple of weeks.

Linda Gibb: We used to go over this bridge every night on the way to the studio. I used to hear this chunka-chunka-chunka, just as we went over the railroad tracks. So I said to Barry, 'Do you ever listen to that rhythm when we go over the bridge at night.' He just looked at me. That night, we were going over the bridge,and I said, 'Listen.' And he said, 'Oh, yeah.' It was the chunka-chunka. Barry started singing something, and the brothers joined in.

Barry Gibb : I just started singing the thing. Robin and Maurice picked up on it and I think we actually finished the song late that night. We went from the studio to home, finished the song and had it ready for recording in the next two days.

Maurice Gibb : We had called it Jive Talkin' but, being British, we thought jive was a dance, so the opening line was 'Jive talkin', you dance with your eyes...'. It was Arif who said to us, 'Don't you guys know what jive talk is?' And he explained that it was black slang for bullshitting, so we changed the lyric to 'Jive talkin', you're telling me lies.'

Barry Gibb : That's also why the first line of the chorus is 'Jive Talkin', so misunderstood.' That's how it really came about.

Blue Weaver : We took the demo back to the house that night and we listened to it over and over, because we knew right away that we'd found the new direction. This was the way to go.

On that very first version, the demo, the drum track was so good that we used it all the way through, just overdubbed the rest on top of it.

Arif Mardin : On Jive Talkin' I remember we used... it was very interesting … we did it to a click, but it was a metronome with a light flashing. The drummer would look at the light flashing to play it, not an audible click but a visual click. So we weren't really getting into cutting edge sounds on Main Course. I think the Main Course album is for me, for my career, very important.

Maurice Gibb : Arif showed us the right track. This was the track leading to RAndB and hits, and that was the track leading to lush ballads and forget it. He just shoved us off that track and right up this one.

Arif Mardin : Jive Talkin' has a 7/4 measure in it that I came up with in the turnarounds. The drums stayed on with 4/4 but the synth part is played in 7/4. Listen to it and you'll find it. That's one of the layers of that record.

Blue Weaver : I played a synth-bassline on it, which was unusual at the time and gave it a distinctive sound, but that only happened by accident. Usually Maurice would play bass guitar, but he was away from the studio that night, so I said I'd find a bass sound on the ARP 2600 and lay down a guide bassline for him. It sounded pretty good, so when Maurice came back, we let him hear it and suggested that he should re-record the bassline on his bass guitar.

It was actually in C, so we got Maurice to tune his low E string down to a C so he plays the down beat, the C, to add the extra weight to the synthesiser, so he's still involved. But I think he would have gone along with it even if he hadn't been involved because everybody could see that it was right.

Arif Mardin : On Jive Talkin', Maurice was playing bass too, but the synth bass was playing some active stuff. So obviously that influenced him. We had two basses going at the same time.

Maurice Gibb : I really liked the synth-bassline, so I just overdubbed certain sections with my bass guitar to add extra emphasis.

Arif Mardin : We weren't trying to make a dance record. The tempo was coming out at about 120bpm, even though we didn't know it at the time, it was an instinct. Apart from seeing Gloria Gaynor, I didn't go into clubs much. Then Ahmet (Ertegun, MD Atlantic Records) and Robert Stigwood (Bee Gee's manager) came into the studio to listen and they both said, 'This is a great dance record.'

Blue Weaver : I expect The Bee Gees felt the pressure but, on the other hand, as soon as the new thing started happening, the pressure was off. You felt you could relax because you knew there was something new there. We all knew there was no way it could not be successful. It was amazing! So it was a great pleasure to be around. Everyone was up; everyone was on a high.

Arif Mardin : We spent fifteen or eighteen hours in the studio every day for two months, and it became like something out of a movie, with everybody being incredibly creative and dynamic.

Usually, when Barry writes the songs, or actually the three brothers write them, Barry would have the electric guitar or the acoustic guitar, and the song would take shape with the instruments they used. And Maurice would go to the piano and play the chords. So it was what they thought the song needed, usually, sometimes acoustic guitar, sometimes electric guitar, that really dictated the sound... It's not like one brother goes into seclusion and comes out with a song. They write them together. In the beginning, their process is that they have nonsensical syllables to accommodate the melody, and then the lyrics come after that. They do the melody first. Most songwriting teams have their own system.

And what happened was that there was a happy marriage of their sound and the orchestral strings, punctuated by a strong beat, which is part of my style.

Blue Weaver : The other thing that changed the Bee Gees sound happened when we were doing Nights On Broadway. I think we'd recorded the song in a key that Barry found difficult to sing his part in. He had to try and take his voice down very low, which was giving him problems.

Arif Mardin : Probably because of my background with Aretha Franklin and all the RAndB greats, I said to Barry, 'Why don't you take it up an octave? I think we need more energy,' and Barry said, 'But I can't!' So I said, 'Try falsetto'. Barry keeps telling it, that I said this, which, obviously if he says that, it's true. But I remember just saying, 'Take it up an octave.' And the only way he could do that was to go into his falsetto. And a certain style was born after that.

Bary Gibb : Arif said to me, 'Can you scream?' I said, 'Under certain circumstances.' He said, 'Can you scream in tune?' I said, 'Well, I'll try'. So he said, 'Go out to the microphone and try some ad-libs on Nights On Broadway, and see if you can do it in a falsetto type music, scream type voice'... I was the one who volunteered to go out there and in doing so, sort of discovered that this voice was hidden back there. Then I started developing it and started singing real songs with the falsetto instead of doing ad-libs with it. It just developed from there.

Arif Mardin : It sounded so good that we kept on using that approach.

Maurice Gibb : Barry didn't even know he could sing like that then; neither did Robin. We just thought, 'Good grief, it isn't just screaming, it's in tune.'

Barry Gibb : Arif called me in and said, 'You know, you really should try to develop that because it's like The Stylistics, it's like Brian Wilson and people like that. They're not afraid to do that. Go and think about it and expand. You know, write with that voice.' It was a feat I was not aware I was capable of.

Blue Weaver : Abandoned Luncheonette by Hall And Oates … that was a heavy influence with Bee Gees' stuff on Main Course. Fanny (Be Tender) - the key changes on that - that was me, but it was a complete rip-off from She's Gone on Abandoned Luncheonette. I was influenced by that, at the time, I'd been listening to that and I only had it on tape, and I didn't know that Arif had produced it, and I'm pinching all these ideas.

Donny Hathaway as well, was a big influence, and Arif produced Donny Hathaway Live as well. We're doing this thing and I'm pinching all these licks, all these ideas, and he said, 'Well, you listened to them, you're influenced by that, you take that and then you go on. If it wasn't right for what you were doing, I would have said. You listen to Hall And Oates' She's Gone, and then listen to Fanny (Be Tender) - it's something that everyone does. That's what Arif said, 'Okay, so it's in She's Gone, it's in hundreds of other songs,' but it just so happened that I had been listening to that and thought, 'Oh, that's great, it's wonderful.'

Barry Gibb : Blue Weaver had a beautiful chord progression while we were in the studio cutting Main Course, and that's how there's a four-way collaboration on Songbird.

Blue Weaver : I'd had it for a long time, since just after Strawbs. It was a chord sequence I had for a long time and not done anything with because I couldn't write lyrics at that time. One night, I was just sitting at the piano just playing that, and Barry walked past and said, 'Oh, that's nice' and started humming along, came up with a melody, and then he sang the word 'songbird'. He's very quick, and usually the first things that come out of his mouth end up actually being part of the lyric and usually the hook...

If you know music, if you look at the way the chords progress, it's a sort of natural progression. It wasn't anything very clever, the clever part was putting a nice melody on top and turning it into a song. I may have changed things slightly once Barry started singing...

Imagine for me going in, and then getting a track on the album - that was amazing in itself. I mean, you look down The Bee Gees' writing credits, and my name sort of stands out. I mean, there's not many other names there.

Robin Gibb : The most positive thing that came off that album was the R'n'B influence. That really just paved the whole way. That's what we wanted to do and we just thanked God that that's what people accepted that we were doing.

Maurice Gibb : We were over the moon about Jive Talkin’, but when we played it to people at the record company, they didn’t want it. They said it wasn’t a good single because it was so different to what we’d done before, and yet they were the very ones who’d told us we had to change.

Stigwood was fighting with them, telling them they were mad and it was a guaranteed number one single, and we were getting secret phone calls from the record company asking us if we could talk him out of it.

Robert came up with a way round it, which was that he sent out some unmarked cassettes to deejays and critics. That way they wouldn’t know who it was, so they’d only come back to us if they liked the music. Then, having said they liked it before they discovered it was the Bee Gees, it was very hard for them not to play it.

Blue Weaver : When I got back to England, I took one down to the Speakeasy and Roger Chapman of Family was there. I got the deejay to put it on without telling Roger who it was, and he loved it, then he said, 'So who was it?' I had to actually tell him it was the Bee Gees. It was that different.

David English (friend of Barry Gibb) : Jack Bruce sent a telegram to the boys saying he'd just heard the record, and he had thought it was the best new black band he'd heard.

Maurice Gibb : There was a party in Robert Stigwood's apartment, and The Rolling Stones were there. Robert just put the album on and didn't tell them who it was, and Mick Jagger says, 'That's fucking dynamite, who's that? Some new group you've signed up?'

Barry Gibb : Because (Jive Talkin’) was a departure from the ballad style that most people associated us with, when it became a hit people started saying that we had stepped down to be a disco group, which was sort of a put-down to disco music as well. We don't think disco is bad music, we think it's happy and has a wide appeal. It's for people to dance to, that's what it's all about.

Maurice Gibb : When it went to No1, it became the start of everything for us again, a complete re-birth.

Barry Gibb : If you look at those clothes now, the way people dressed then, you had to be fairly naive. To go around like that and feel that you looked great, there was a naivete that comes with that. If you look back, you think, Shit, everyone looked like a clown.

Robin Gibb : It should be stated that when Jive Talkin' came out, disco music wasn't very big, not in the sense that it has become, so how could we have been capitalising?

Tweet this Fact

Barry Gibb : We got into pills - Dexedrine - and liquor too. The only thing that we never got involved with was LSD.

Maurice Gibb : Part of the problem was that our manager, Robert Stigwood, had become so involved with stage shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and movies, that he'd taken his eye off us, and we were kind of drifting.

Barry Gibb : We ended up in Batley Variety Club. It was a little club up north and, if you ended up working there it can be safely said that you're not required anywhere else. In those days, that was the place not to work in, and we ended up working there.

I remember us talking about it backstage at that place and I said, 'If this is the bottom, there's no further we can fall. Something's gotta happen for the positive.'

Blue Weaver (keyboards) : The Bee Gees drummer then was Dennis Byron who'd been in Amen Corner with me years before, and he rang me up to ask if I'd be interested in joining the band. They'd realised they had to change direction, and they were trying to inject some fresh ideas into the band. In December of 1974 I had a meeting with them where they lived, in the Isle Of Man.

I went over and stayed with Barry for the weekend - went over on Friday night and came back on the Sunday night. As I'm leaving, I'm walking out the door, and Barry says, 'Here! I haven't heard you play piano yet!' I was actually putting my bags in the car, and I said, 'Oh, do you have a piano?' They had this old thing in the back - it was all out of tune … I rattled out a quick tune on the piano and they said, 'Fine, can you come to Miami next month?' So I agreed to start work with them at Criteria Studios on January 2, because that had been recommended to them by Eric Clapton…

Barry Gibb : We had a conversation with Eric Clapton about making a comeback because he was trying to make a comeback, and we were always trying to make a comeback. Eric said, 'I've just made this album called 461 Ocean Boulevard in Miami. Why don't you guys go to America and do the same and maybe the change of environment will do something for you?' I think it was really good advice...

Blue Weaver : We all moved into 461 on Golden Beach, and started writing material there. Basically we'd lie all day on the beach, then work over at the studio in the evening, and late into the night.

When I joined, I think it was the lowest ebb that the three brothers had been. I'd actually heard Mr. Natural as well, and I thought that was great, and there were elements in that that I obviously felt we could take further.

I got a little bit worried at first...we all have personal problems, but sometimes the personal problems overrun into-well, we were all living in one house so there was no way that you could hide anything that goes on. If one person drinks a little too much, everybody else is gonna know about it.

There were a few things to overcome, and obviously politics as well, if you're going to change something. If Maurice, for instance, had been playing the piano, and suddenly you decide that I'm going to play the piano or something like that, then you have to be a little diplomatic and break things in gently. As soon as they could see the potential, as soon as we started doing things, there was no problem.

Maurice Gibb : The drink and drugs didn't stop when we went to Miami. We were known affectionately throughout the music business as Pilly, Potty and Pissy, because I was the piss artist, Barry was the pot-head and Robin was the pill-head, but we were determined to change, and we asked for Arif Mardin of Atlantic Records as producer, because we'd had a good experience working with him on the previous album, Mr Natural.

Barry Gibb : Quite simply, [Arif is] the best producer in the world for us. In that studio with him is magic. There isn't any certain kind of technique or attitude that he uses. He's totally like an uncle. He rolls in there with you. As far as a song is concerned, you take it to him. He says the song is fantastic; however, put that verse there, that chorus there. He's that kind of producer - doesn't take the song away from you, he just places it where he thinks it should be. He brought it out of us again. We knew we couldn't go in there and make another album that wasn't going to go.

Robin Gibb : Our roots was the R'n'B music, but we didn't know what direction would be best to go in. So Main Course was several directions, country with songs like Come On Over, and R'n'B with songs like Nights On Broadway and Jive Talkin'.

Maurice Gibb : The house engineer at Criteria when we arrived was a guy called Karl Richardson. Karl knew this other guy, Albhy Galuten who had worked with Clapton and such. The first time I saw him he was barefoot, eating his bloody grease tree [avocado] sandwiches, and he looked quite alarming. I was a bit frightened by him. He was a keyboard player who had his own studio and did a few things. He didn’t work on Main Course, but he became part of the team on the later albums.

Arif Mardin (producer) : We started to record, and some of the songs were still in their old ballad style.

Linda Gibb (wife of Barry Gibb) :They were in the studio putting some tracks down. Dick [Ashby] and Tom [Kennedy] and I were the onlookers, and we were looking at each other and thinking, 'This isn't what's happening now. They've got to write something more up-tempo.'

Ahmet Ertegun (MD, Atlantic Records) : After Arif took over, they went over into a whole new RAndB direction, and disco... Arif did a lot for the group. And they did a lot for Arif. That was one of Arif's great successes in his career.

Blue Weaver : Although the brief, from the start, was to find a new direction, the first songs we worked on, Was It All In Vain and Our Love Will Save The World, were actually in the same old Bee Gees ballad style, and when their manager Robert Stigwood heard the tapes we sent him, he wasn't impressed.

The first song that we all realised that that we'd hit on something that was going to develop was Wind Of Change. I knew that we were going to come away with a hit album no matter what - I mean, we all did, I think. It was just finding out direction... I mean, nobody had any doubts about things not happening.

Barry Gibb : One of the first four songs we came up with and played to Arif was Wind Of Change. He took those songs to Atlantic and played them, and they didn't like them.

Robin Gibb : Ahmet was so quick to turn off to us, to say, 'This is it?' We thought they weren't even going to give us a chance. They were burying us. Only Arif, of all the Atlantic people, kept faith in us.

Barry Gibb : Atlantic wasn't at all prepared to go that way because we hadn't had successful albums for about four or five years.

Maurice Gibb : Stigwood and Ahmet Ertegun flew down, and told us they didn't like the songs. We were devastated, but Stigwood sat on Golden Beach with us and apologised for having been so distant from us, and said, 'I'm determined to get involved again.'

Robert Stigwood (manager, Bee Gees) : I didn't like a lot of the tracks. I flew down to Miami and told them I wanted to scrap a lot of the things they'd done, and I'd like them to start again. I would swallow the costs, not to worry, but to really open their ears and find out in contemporary terms what is going on.

Barry Gibb : We had been writing about politics and saving the world for so many years, and we decided that we would try something light-hearted, and we did. We didn't cunningly go into the disco market to gain greater strength in the record market, as some people implied at the time. We simply tried to embrace all kinds of music, whatever music there was.

It was more about getting back into the music we were always into, which was RAndB. When we arrived in Florida, the place teemed with it. Here was a new culture to absorb, to base our music on. That's basically what we've done all our lives. Everything sprang from our deep love of RAndB - Al Green, Otis Redding, the Stylistics.

So we went to work with Arif, and he said, 'I'm going away for a week and I want you to write while I'm away. During the week he was away, we wrote Jive Talkin', Nights On Broadway, Edge Of The Universe. All those songs we wrote in one week, simple because we knew that this was it. If this album doesn't work, it's the finish for our recording career.

Blue Weaver : During Main Course, the sound changed so drastically because synthesisers were used, and technology was introduced rather than just an orchestra and a piano. That was a change as well. There hasn't been musically much change since then because nothing new has been invented to make such a tremendous difference to the sound as the synthesiser did, compared to an orchestra.

Arif Mardin : We would try many things, like synthesisers … At that time, I think Stevie Wonder was using synthesiser bass. Only certain people were using synthesisers, and Stevie was one of them. I used to use synthesiser too, before we recorded them but, at that time, they were very primitive. They were monophonic. If you wanted to play a chord, the guy had to play three notes, three times, and stack the harmonies up.

Robin Gibb : The actual track that started it all off was Jive Talkin'. That snowballed one night and the energy went on for a couple of weeks.

Linda Gibb: We used to go over this bridge every night on the way to the studio. I used to hear this chunka-chunka-chunka, just as we went over the railroad tracks. So I said to Barry, 'Do you ever listen to that rhythm when we go over the bridge at night.' He just looked at me. That night, we were going over the bridge,and I said, 'Listen.' And he said, 'Oh, yeah.' It was the chunka-chunka. Barry started singing something, and the brothers joined in.

Barry Gibb : I just started singing the thing. Robin and Maurice picked up on it and I think we actually finished the song late that night. We went from the studio to home, finished the song and had it ready for recording in the next two days.

Maurice Gibb : We had called it Jive Talkin' but, being British, we thought jive was a dance, so the opening line was 'Jive talkin', you dance with your eyes...'. It was Arif who said to us, 'Don't you guys know what jive talk is?' And he explained that it was black slang for bullshitting, so we changed the lyric to 'Jive talkin', you're telling me lies.'

Barry Gibb : That's also why the first line of the chorus is 'Jive Talkin', so misunderstood.' That's how it really came about.

Blue Weaver : We took the demo back to the house that night and we listened to it over and over, because we knew right away that we'd found the new direction. This was the way to go.

On that very first version, the demo, the drum track was so good that we used it all the way through, just overdubbed the rest on top of it.

Arif Mardin : On Jive Talkin' I remember we used... it was very interesting … we did it to a click, but it was a metronome with a light flashing. The drummer would look at the light flashing to play it, not an audible click but a visual click. So we weren't really getting into cutting edge sounds on Main Course. I think the Main Course album is for me, for my career, very important.

Maurice Gibb : Arif showed us the right track. This was the track leading to RAndB and hits, and that was the track leading to lush ballads and forget it. He just shoved us off that track and right up this one.

Arif Mardin : Jive Talkin' has a 7/4 measure in it that I came up with in the turnarounds. The drums stayed on with 4/4 but the synth part is played in 7/4. Listen to it and you'll find it. That's one of the layers of that record.

Blue Weaver : I played a synth-bassline on it, which was unusual at the time and gave it a distinctive sound, but that only happened by accident. Usually Maurice would play bass guitar, but he was away from the studio that night, so I said I'd find a bass sound on the ARP 2600 and lay down a guide bassline for him. It sounded pretty good, so when Maurice came back, we let him hear it and suggested that he should re-record the bassline on his bass guitar.

It was actually in C, so we got Maurice to tune his low E string down to a C so he plays the down beat, the C, to add the extra weight to the synthesiser, so he's still involved. But I think he would have gone along with it even if he hadn't been involved because everybody could see that it was right.

Arif Mardin : On Jive Talkin', Maurice was playing bass too, but the synth bass was playing some active stuff. So obviously that influenced him. We had two basses going at the same time.

Maurice Gibb : I really liked the synth-bassline, so I just overdubbed certain sections with my bass guitar to add extra emphasis.

Arif Mardin : We weren't trying to make a dance record. The tempo was coming out at about 120bpm, even though we didn't know it at the time, it was an instinct. Apart from seeing Gloria Gaynor, I didn't go into clubs much. Then Ahmet (Ertegun, MD Atlantic Records) and Robert Stigwood (Bee Gee's manager) came into the studio to listen and they both said, 'This is a great dance record.'

Blue Weaver : I expect The Bee Gees felt the pressure but, on the other hand, as soon as the new thing started happening, the pressure was off. You felt you could relax because you knew there was something new there. We all knew there was no way it could not be successful. It was amazing! So it was a great pleasure to be around. Everyone was up; everyone was on a high.

Arif Mardin : We spent fifteen or eighteen hours in the studio every day for two months, and it became like something out of a movie, with everybody being incredibly creative and dynamic.

Usually, when Barry writes the songs, or actually the three brothers write them, Barry would have the electric guitar or the acoustic guitar, and the song would take shape with the instruments they used. And Maurice would go to the piano and play the chords. So it was what they thought the song needed, usually, sometimes acoustic guitar, sometimes electric guitar, that really dictated the sound... It's not like one brother goes into seclusion and comes out with a song. They write them together. In the beginning, their process is that they have nonsensical syllables to accommodate the melody, and then the lyrics come after that. They do the melody first. Most songwriting teams have their own system.

And what happened was that there was a happy marriage of their sound and the orchestral strings, punctuated by a strong beat, which is part of my style.

Blue Weaver : The other thing that changed the Bee Gees sound happened when we were doing Nights On Broadway. I think we'd recorded the song in a key that Barry found difficult to sing his part in. He had to try and take his voice down very low, which was giving him problems.

Arif Mardin : Probably because of my background with Aretha Franklin and all the RAndB greats, I said to Barry, 'Why don't you take it up an octave? I think we need more energy,' and Barry said, 'But I can't!' So I said, 'Try falsetto'. Barry keeps telling it, that I said this, which, obviously if he says that, it's true. But I remember just saying, 'Take it up an octave.' And the only way he could do that was to go into his falsetto. And a certain style was born after that.

Bary Gibb : Arif said to me, 'Can you scream?' I said, 'Under certain circumstances.' He said, 'Can you scream in tune?' I said, 'Well, I'll try'. So he said, 'Go out to the microphone and try some ad-libs on Nights On Broadway, and see if you can do it in a falsetto type music, scream type voice'... I was the one who volunteered to go out there and in doing so, sort of discovered that this voice was hidden back there. Then I started developing it and started singing real songs with the falsetto instead of doing ad-libs with it. It just developed from there.

Arif Mardin : It sounded so good that we kept on using that approach.

Maurice Gibb : Barry didn't even know he could sing like that then; neither did Robin. We just thought, 'Good grief, it isn't just screaming, it's in tune.'

Barry Gibb : Arif called me in and said, 'You know, you really should try to develop that because it's like The Stylistics, it's like Brian Wilson and people like that. They're not afraid to do that. Go and think about it and expand. You know, write with that voice.' It was a feat I was not aware I was capable of.

Blue Weaver : Abandoned Luncheonette by Hall And Oates … that was a heavy influence with Bee Gees' stuff on Main Course. Fanny (Be Tender) - the key changes on that - that was me, but it was a complete rip-off from She's Gone on Abandoned Luncheonette. I was influenced by that, at the time, I'd been listening to that and I only had it on tape, and I didn't know that Arif had produced it, and I'm pinching all these ideas.

Donny Hathaway as well, was a big influence, and Arif produced Donny Hathaway Live as well. We're doing this thing and I'm pinching all these licks, all these ideas, and he said, 'Well, you listened to them, you're influenced by that, you take that and then you go on. If it wasn't right for what you were doing, I would have said. You listen to Hall And Oates' She's Gone, and then listen to Fanny (Be Tender) - it's something that everyone does. That's what Arif said, 'Okay, so it's in She's Gone, it's in hundreds of other songs,' but it just so happened that I had been listening to that and thought, 'Oh, that's great, it's wonderful.'

Barry Gibb : Blue Weaver had a beautiful chord progression while we were in the studio cutting Main Course, and that's how there's a four-way collaboration on Songbird.

Blue Weaver : I'd had it for a long time, since just after Strawbs. It was a chord sequence I had for a long time and not done anything with because I couldn't write lyrics at that time. One night, I was just sitting at the piano just playing that, and Barry walked past and said, 'Oh, that's nice' and started humming along, came up with a melody, and then he sang the word 'songbird'. He's very quick, and usually the first things that come out of his mouth end up actually being part of the lyric and usually the hook...

If you know music, if you look at the way the chords progress, it's a sort of natural progression. It wasn't anything very clever, the clever part was putting a nice melody on top and turning it into a song. I may have changed things slightly once Barry started singing...

Imagine for me going in, and then getting a track on the album - that was amazing in itself. I mean, you look down The Bee Gees' writing credits, and my name sort of stands out. I mean, there's not many other names there.

Robin Gibb : The most positive thing that came off that album was the R'n'B influence. That really just paved the whole way. That's what we wanted to do and we just thanked God that that's what people accepted that we were doing.

Maurice Gibb : We were over the moon about Jive Talkin’, but when we played it to people at the record company, they didn’t want it. They said it wasn’t a good single because it was so different to what we’d done before, and yet they were the very ones who’d told us we had to change.

Stigwood was fighting with them, telling them they were mad and it was a guaranteed number one single, and we were getting secret phone calls from the record company asking us if we could talk him out of it.

Robert came up with a way round it, which was that he sent out some unmarked cassettes to deejays and critics. That way they wouldn’t know who it was, so they’d only come back to us if they liked the music. Then, having said they liked it before they discovered it was the Bee Gees, it was very hard for them not to play it.

Blue Weaver : When I got back to England, I took one down to the Speakeasy and Roger Chapman of Family was there. I got the deejay to put it on without telling Roger who it was, and he loved it, then he said, 'So who was it?' I had to actually tell him it was the Bee Gees. It was that different.

David English (friend of Barry Gibb) : Jack Bruce sent a telegram to the boys saying he'd just heard the record, and he had thought it was the best new black band he'd heard.

Maurice Gibb : There was a party in Robert Stigwood's apartment, and The Rolling Stones were there. Robert just put the album on and didn't tell them who it was, and Mick Jagger says, 'That's fucking dynamite, who's that? Some new group you've signed up?'

Barry Gibb : Because (Jive Talkin’) was a departure from the ballad style that most people associated us with, when it became a hit people started saying that we had stepped down to be a disco group, which was sort of a put-down to disco music as well. We don't think disco is bad music, we think it's happy and has a wide appeal. It's for people to dance to, that's what it's all about.

Maurice Gibb : When it went to No1, it became the start of everything for us again, a complete re-birth.

Barry Gibb : If you look at those clothes now, the way people dressed then, you had to be fairly naive. To go around like that and feel that you looked great, there was a naivete that comes with that. If you look back, you think, Shit, everyone looked like a clown.

Robin Gibb : It should be stated that when Jive Talkin' came out, disco music wasn't very big, not in the sense that it has become, so how could we have been capitalising?