Fact #164314

When:

Short story:

Donald Fagen releases his first solo LP, The Nightfly, on Warner Bros. Records in the USA.

Donald Fagen releases his first solo LP, The Nightfly, on Warner Bros. Records in the USA.Full article:

DONALD FAGEN - THE NIGHTFLY

By Johnny Black

This feature first appeared in Hi Fi News, as part of a series entitled Vinyl Icons.

Having established himself in the 1970s as half of the acclaimed thinking person’s rock duo Steely Dan, Donald Fagen became a solo performer in 1981 when his partnership with Walter Becker fell apart.

Released on October 1, 1982, The Nightfly was Fagen’s first solo album and, although similarities to his work in Steely Dan abounded, there were also dramatic differences. For starters, whereas much of Steely Dan’s output had been in the form of cryptic, fictionalised story songs, most of the lyrics on The Nightfly were clearly autobiographical.

"I used to live 50 miles outside New York City in one of those rows of prefab houses," Fagen explained. "It was a bland environment. One of my only escapes was late-night radio shows broadcast from Manhattan – jazz and rhythm and blues. To me, the DJs were romantic and colourful figures and the whole hipster culture of black lifestyles seemed much more vital to a kid living in the suburbs."

So when he started work on The Nightfly, Fagen set out to explore and document how those early experiences affected his - and much of his generation’s - outlook on life. As the songs took shape, the work evolved into something like a concept album, held together by an imaginary deejay Fagen invented by the name of Lester The Nightfly.

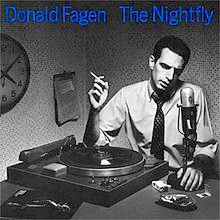

On the cover of the album Fagen portrays the imaginary Nightfly, a late-night radio jock, seated behind a turntable with a cigarette in his right hand, while his left is wrapped around the base of an RCA 77DX microphone. The music on the album represents how a late-1950s teenager might have viewed the era, with the Nightfly as his musical guru, shaping his life decisions with judiciously chosen songs.

Fagen has said that, as a young man, he was looking for alternatives to the 50’s lifestyle, including, "the political climate, the sexual repression, the fact that the technological advances of the period didn't seem to have a guiding humanistic philosophy behind them. A lot of kids were looking for alternatives, and it's amazing how many of us found them in jazz, in other kinds of black music, in science fiction and in the sort of hip ideas and attitudes we could pick up on the late-night radio talk shows."

He started the project in 1981at The Village Recorder studios in Los Angeles, bringing in an impressive array of top session talent, many of whom had played previously on Steely Dan albums. Larry Carlton and Hugh McCracken, for example, were prominent among the guitarists, with Greg Phillinganes and Michael Omartian handling keyboards, Jeff Porcaro and Ed Green playing drums, The Brecker Brothers on horns. With such familiar names, its hardly surprising that the end results frequently recalled Steely Dan, particularly on its later, mellower albums.

The Nightfly sits at the start of the digital recording era and, given Fagen’s obsession with achieving perfect audio, it was natural for him to want to explore digital. He had started down that path on Steely Dan’s 1980 release Gaucho, but Nightfly was his first attempt at a fully digital album.

The album opens with I.G.Y., the initials standing for International Geophysical Year, which started on July 1, 1957 and ended 18 months later on December 31, 1958. The I.G.Y. was intended to usher in a new era of global scientific collaboration in the wake of the end of the Cold War, and Fagen’s breezy, jazz-inflected song seems, at first listen, to celebrate the optimism of the I.G.Y. concept, declaring, "What a beautiful world this will be, What a glorious time to be free."

But anyone familiar with Steely Dan inevitably wonders whether this apparently euphoric vision of the future is real or ironic.

According to Fagen himself, "I actually tried to write these new songs with as little irony as possible." He went on to say, "I wanted this album to be a little brighter and a little lighter than a Steely Dan record. I wanted it to be more fun to listen to. And I wanted to make an album that was more personal…"

Recalling the sessions some years later, Fagen revealed, "With I.G.Y. we started out with a rhythm machine to get the feel, then used a sequenced synth for the backbeats, then I put down a bassline for reference using the piano, then Greg Phillinganes came in to put the basic thing down with the Rhodes. At that point, we had the basic track."

It’s interesting that, although the album was an attempt to evoke the 1950s, Fagen’s methodology was the polar opposite of that era’s "1,2,3,4!" live in the studio approach to making records.

As always, Fagen’s perfectionism made demands on his players that went above and beyond the call of duty. During his brilliantly arranged cover of the 1956 Drifters’ hit Ruby Baby, for example, he demanded isolation between the left and right hand parts on the piano in order to achieve a left hand that was more laid-back than the right. "I tell you," said Michael Omartian, "there’s no piano player on the face of the earth that could accommodate that."

Fagen was only able to achieve what he visualised by having Omartian and Greg Phillinganes sit side by side at the keyboard with each man playing the part for only one hand.

Fagen’s perfectionism was also evident in his time-consuming approach to recording his vocals. Chief engineer Roger Nichols has stated that Fagen would record his vocals over and over again, using the newly available digital technology to patch together one complete take from the phrases and fragments of lines which he felt were the best. "As far as the general public is concerned," reckoned Nichols, "the first or second take would have been just fine and everybody would have been happy with it - except Donald."

The dance-groove oriented New Frontier offers arguably the most Dan-like lyric on Nightfly, with Fagen hitting on a Tuesday Weld lookalike at a party in the family bomb shelter. "I was trying to show how ridiculous fall out shelters were," he explained. "The concept that there was any real life possible after an all-out nuclear war. I thought having a party was a good way to display that in a funny sort of way."

Whether it’s The Goodbye Look with its superb bossa nova grooves, Walk Between Raindrops where Phillinganes’ keyboard bass is doubled with Will Lee’s electric bass to achieve a weird simulation of an acoustic upright bass or the title track in which Fagen conjures up the spirit of his imaginary deejay, there’s no filler on this album. Every track can be heard again and again, and every listen will yield previously unnoticed and enticing details.

"During the final mix down of the album, I started to feel kind of funny," Fagen has subsequently owned up. "And that feeling turned into an even weirder feeling that had to do with work and love and the past and morality and so forth. I wouldn’t complete another CD until 1993. So I’m glad I made The Nightfly before a lot of the kid-ness was beat the hell out of me, as happens to us all."

On its release, The Nightfly sold well, reaching No11 on the Billboard chart, with the first single, I.G.Y., peaking at No8 on the Adult Contemporary chart. Although the subsequent singles, New Frontier and Ruby Baby, didn’t do so well, the album eventually achieved platinum status in the the USA and UK.

Despite its commercial success, the album seems to have taken a personal toll on Fagen, and he went into therapy soon after its completion. "I had come to the end of whatever kind of energy was behind the writing I had been doing in the '70s, and The Nightfly sort of summed it up for me in a way. And although I would work every day, I essentially was blocked because I didn't like what I was doing. I'd write a song and then a week later I just wouldn't connect with it at all. It seemed either I was repeating myself, or it just bored me. It wasn't relevant to what I was going through at the time."

Thankfully, Fagen did eventually overcome his psychological problems, but what no-one knew in 1982, was that The Nightfly would eventually have to be perceived as part of a trilogy. Fagen has since gone on record stating that his three solo albums are thematically connected, with The Nightfly presenting the perspective of a young man, 1993’s Kamakiriad showing the outlook of the artist in middle-age, and 2006’s Morph The Cat revealing the thoughts of a man in the final stages of his life.

PRODUCTION NOTES

The Nightfly was recorded and mixed entirely on 3M Digital 32-track and 4-track machines at Village Recorders in Los Angeles, and at Soundworks and Automated Sound in New York. Bop Til You Drop (1979) by Ry Cooder was the first fully digital rock album, but The Nightfly was nonetheless an early entrant in the field.

However, Donald Fagen had begun working with digital systems somewhat earlier than 1982.

"We started using sequencing and stuff on [Steely Dan's] Gaucho," he has explained, "out of desperation really. We were having trouble laying down Hey Nineteen. We tried it with two different bands and it still didn't work, so one of us said something like, 'It's too bad that we can't get a machine to play the beat we want, with full-frequency drum sounds, and to be able to move the snare drum and kick drum around independently.'"

When engineer Roger Nichols said it could be done for $150,000, the band advanced him the money, and he came up with Wendel, based on a CompuPro S100 computer with a CPM/86 operating system. This first 8-bit incarnation of Wendel could replace and move around previously recorded sounds, so that drum tracks didn’t have to be created from scratch.

By the time of The Nightfly, Nichols had developed Wendel II, a somewhat faster and more versatile 16-bit version, which plugged directly into the 3M digital recorders, so there was no degrading of recorded sound.

On The Nightfly, Wendel provided the core drum tracks on Ruby Baby, I.G.Y., and Walk Between Raindrops, but also embellished other tracks and was used for repairs here and there.

Eventually, Fagen would move away from sampling, but he continued to champion digital as a viable alternative to analogue recording. "Most of the way a record sounds is independent of whether it was recorded digital or analogue," he has argued. "So much has to do with the miking, the material, the studios, and the engineer. Having said that, I do think that digital has improved a lot over the years … but frankly I don't hear that much of a difference between the two media."

Tweet this Fact

By Johnny Black

This feature first appeared in Hi Fi News, as part of a series entitled Vinyl Icons.

Having established himself in the 1970s as half of the acclaimed thinking person’s rock duo Steely Dan, Donald Fagen became a solo performer in 1981 when his partnership with Walter Becker fell apart.

Released on October 1, 1982, The Nightfly was Fagen’s first solo album and, although similarities to his work in Steely Dan abounded, there were also dramatic differences. For starters, whereas much of Steely Dan’s output had been in the form of cryptic, fictionalised story songs, most of the lyrics on The Nightfly were clearly autobiographical.

"I used to live 50 miles outside New York City in one of those rows of prefab houses," Fagen explained. "It was a bland environment. One of my only escapes was late-night radio shows broadcast from Manhattan – jazz and rhythm and blues. To me, the DJs were romantic and colourful figures and the whole hipster culture of black lifestyles seemed much more vital to a kid living in the suburbs."

So when he started work on The Nightfly, Fagen set out to explore and document how those early experiences affected his - and much of his generation’s - outlook on life. As the songs took shape, the work evolved into something like a concept album, held together by an imaginary deejay Fagen invented by the name of Lester The Nightfly.

On the cover of the album Fagen portrays the imaginary Nightfly, a late-night radio jock, seated behind a turntable with a cigarette in his right hand, while his left is wrapped around the base of an RCA 77DX microphone. The music on the album represents how a late-1950s teenager might have viewed the era, with the Nightfly as his musical guru, shaping his life decisions with judiciously chosen songs.

Fagen has said that, as a young man, he was looking for alternatives to the 50’s lifestyle, including, "the political climate, the sexual repression, the fact that the technological advances of the period didn't seem to have a guiding humanistic philosophy behind them. A lot of kids were looking for alternatives, and it's amazing how many of us found them in jazz, in other kinds of black music, in science fiction and in the sort of hip ideas and attitudes we could pick up on the late-night radio talk shows."

He started the project in 1981at The Village Recorder studios in Los Angeles, bringing in an impressive array of top session talent, many of whom had played previously on Steely Dan albums. Larry Carlton and Hugh McCracken, for example, were prominent among the guitarists, with Greg Phillinganes and Michael Omartian handling keyboards, Jeff Porcaro and Ed Green playing drums, The Brecker Brothers on horns. With such familiar names, its hardly surprising that the end results frequently recalled Steely Dan, particularly on its later, mellower albums.

The Nightfly sits at the start of the digital recording era and, given Fagen’s obsession with achieving perfect audio, it was natural for him to want to explore digital. He had started down that path on Steely Dan’s 1980 release Gaucho, but Nightfly was his first attempt at a fully digital album.

The album opens with I.G.Y., the initials standing for International Geophysical Year, which started on July 1, 1957 and ended 18 months later on December 31, 1958. The I.G.Y. was intended to usher in a new era of global scientific collaboration in the wake of the end of the Cold War, and Fagen’s breezy, jazz-inflected song seems, at first listen, to celebrate the optimism of the I.G.Y. concept, declaring, "What a beautiful world this will be, What a glorious time to be free."

But anyone familiar with Steely Dan inevitably wonders whether this apparently euphoric vision of the future is real or ironic.

According to Fagen himself, "I actually tried to write these new songs with as little irony as possible." He went on to say, "I wanted this album to be a little brighter and a little lighter than a Steely Dan record. I wanted it to be more fun to listen to. And I wanted to make an album that was more personal…"

Recalling the sessions some years later, Fagen revealed, "With I.G.Y. we started out with a rhythm machine to get the feel, then used a sequenced synth for the backbeats, then I put down a bassline for reference using the piano, then Greg Phillinganes came in to put the basic thing down with the Rhodes. At that point, we had the basic track."

It’s interesting that, although the album was an attempt to evoke the 1950s, Fagen’s methodology was the polar opposite of that era’s "1,2,3,4!" live in the studio approach to making records.

As always, Fagen’s perfectionism made demands on his players that went above and beyond the call of duty. During his brilliantly arranged cover of the 1956 Drifters’ hit Ruby Baby, for example, he demanded isolation between the left and right hand parts on the piano in order to achieve a left hand that was more laid-back than the right. "I tell you," said Michael Omartian, "there’s no piano player on the face of the earth that could accommodate that."

Fagen was only able to achieve what he visualised by having Omartian and Greg Phillinganes sit side by side at the keyboard with each man playing the part for only one hand.

Fagen’s perfectionism was also evident in his time-consuming approach to recording his vocals. Chief engineer Roger Nichols has stated that Fagen would record his vocals over and over again, using the newly available digital technology to patch together one complete take from the phrases and fragments of lines which he felt were the best. "As far as the general public is concerned," reckoned Nichols, "the first or second take would have been just fine and everybody would have been happy with it - except Donald."

The dance-groove oriented New Frontier offers arguably the most Dan-like lyric on Nightfly, with Fagen hitting on a Tuesday Weld lookalike at a party in the family bomb shelter. "I was trying to show how ridiculous fall out shelters were," he explained. "The concept that there was any real life possible after an all-out nuclear war. I thought having a party was a good way to display that in a funny sort of way."

Whether it’s The Goodbye Look with its superb bossa nova grooves, Walk Between Raindrops where Phillinganes’ keyboard bass is doubled with Will Lee’s electric bass to achieve a weird simulation of an acoustic upright bass or the title track in which Fagen conjures up the spirit of his imaginary deejay, there’s no filler on this album. Every track can be heard again and again, and every listen will yield previously unnoticed and enticing details.

"During the final mix down of the album, I started to feel kind of funny," Fagen has subsequently owned up. "And that feeling turned into an even weirder feeling that had to do with work and love and the past and morality and so forth. I wouldn’t complete another CD until 1993. So I’m glad I made The Nightfly before a lot of the kid-ness was beat the hell out of me, as happens to us all."

On its release, The Nightfly sold well, reaching No11 on the Billboard chart, with the first single, I.G.Y., peaking at No8 on the Adult Contemporary chart. Although the subsequent singles, New Frontier and Ruby Baby, didn’t do so well, the album eventually achieved platinum status in the the USA and UK.

Despite its commercial success, the album seems to have taken a personal toll on Fagen, and he went into therapy soon after its completion. "I had come to the end of whatever kind of energy was behind the writing I had been doing in the '70s, and The Nightfly sort of summed it up for me in a way. And although I would work every day, I essentially was blocked because I didn't like what I was doing. I'd write a song and then a week later I just wouldn't connect with it at all. It seemed either I was repeating myself, or it just bored me. It wasn't relevant to what I was going through at the time."

Thankfully, Fagen did eventually overcome his psychological problems, but what no-one knew in 1982, was that The Nightfly would eventually have to be perceived as part of a trilogy. Fagen has since gone on record stating that his three solo albums are thematically connected, with The Nightfly presenting the perspective of a young man, 1993’s Kamakiriad showing the outlook of the artist in middle-age, and 2006’s Morph The Cat revealing the thoughts of a man in the final stages of his life.

PRODUCTION NOTES

The Nightfly was recorded and mixed entirely on 3M Digital 32-track and 4-track machines at Village Recorders in Los Angeles, and at Soundworks and Automated Sound in New York. Bop Til You Drop (1979) by Ry Cooder was the first fully digital rock album, but The Nightfly was nonetheless an early entrant in the field.

However, Donald Fagen had begun working with digital systems somewhat earlier than 1982.

"We started using sequencing and stuff on [Steely Dan's] Gaucho," he has explained, "out of desperation really. We were having trouble laying down Hey Nineteen. We tried it with two different bands and it still didn't work, so one of us said something like, 'It's too bad that we can't get a machine to play the beat we want, with full-frequency drum sounds, and to be able to move the snare drum and kick drum around independently.'"

When engineer Roger Nichols said it could be done for $150,000, the band advanced him the money, and he came up with Wendel, based on a CompuPro S100 computer with a CPM/86 operating system. This first 8-bit incarnation of Wendel could replace and move around previously recorded sounds, so that drum tracks didn’t have to be created from scratch.

By the time of The Nightfly, Nichols had developed Wendel II, a somewhat faster and more versatile 16-bit version, which plugged directly into the 3M digital recorders, so there was no degrading of recorded sound.

On The Nightfly, Wendel provided the core drum tracks on Ruby Baby, I.G.Y., and Walk Between Raindrops, but also embellished other tracks and was used for repairs here and there.

Eventually, Fagen would move away from sampling, but he continued to champion digital as a viable alternative to analogue recording. "Most of the way a record sounds is independent of whether it was recorded digital or analogue," he has argued. "So much has to do with the miking, the material, the studios, and the engineer. Having said that, I do think that digital has improved a lot over the years … but frankly I don't hear that much of a difference between the two media."