Fact #149511

When:

Short story:

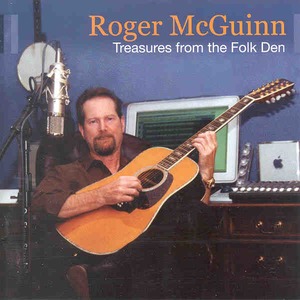

Roger McGuinn releases a new LP, Treasures From The Folk Den, on Appleseed Records in the USA.

Roger McGuinn releases a new LP, Treasures From The Folk Den, on Appleseed Records in the USA.Full article:

Roger McGuinn: Twelve-string Driven Thing

Johnny Black, MOJO, September 2002

THE OPENING JINGLE-JANGLE 12-string Rickenbacker guitar line on The Byrds' 1965 classic, 'Mr Tambourine Man', ushered in a new era in popular music – the folk rock boom that spawned The Mamas And The Papas, Simon And Garfunkel, Fairport Convention and too many more to mention.

Not content with inventing one new genre, The Byrds were in the vanguard of so many emerging styles – from psychedelia to space rock, raga rock and country rock – that it seemed as if each successive album heralded a new epoch. And although many gifted musicians passed through the ranks, there was just one consistent factor throughout their entire career – the original techno-folkie, Roger McGuinn.

Now based in Florida, McGuinn continues to perform and record to considerable acclaim as a solo artist. His latest album, the Grammy-nominated Treasures From The Folk Den, explores his renewed love affair with the traditional folk songs that first inspired him, and he has recently toured the UK.

"Just me and two guitars – a Rickenbacker and an acoustic 12-string," he says. "I play a lot of traditional material, but I never forget that people want to hear The Byrds songs too, so I always do some of those too."

The earliest Byrds songs on record appear on Preflyte, but those weren't official recordings.

Those were really rehearsal tapes. Our manager Jim Dickson had access to the World Pacific Recording studio, and he offered it to us free if we'd go in after midnight when all the other sessions were closed down. He had old tapes that were all spliced together, not good enough for masters, and he let us practise with those. So we were just recording the tracks and listening back to see how we could improve them.

Did those demos prompt Miles Davis to get you signed to Columbia?

We never actually met Miles. His agent, Benny Shapiro, was a friend of Dickson's, so Gene Clark, David Crosby and I put a little backing tape together and went over to Benny's, and we sang with this tape in his living-room. Benny's teenage daughter was upstairs and when she heard us, she flipped out. She thought The Beatles were in her living room. The next day, Miles came by and Benny told him what had happened. Miles said, "Kids know stuff like that. You should pay attention." And on the strength of that Benny called up Columbia Records, which led to the deal.

Of all the available Dylan material, why did you pick 'Mr Tambourine Man' as the first Byrds single?

That was Dickson. He admired Dylan as a writer, so he'd been working with that and other Dylan songs in bluegrass with Vern Gosdin and Chris Hillman – who became The Byrds' bassist. 'Tambourine Man' was out as a demo but Columbia had shelved it because Ramblin' Jack Elliott was on the track and he was a bit inebriated, sounded a little out of tune, out of time. So Dickson had a copy sent out to LA from New York and we learned it. Initially, David Crosby didn't like it at all. He didn't like the sound of Dylan's voice. And by that point we were all getting into The Beatles, so David was a little down on folk music, and we wanted to do a Beatley kind of thing. We didn't want to do a folky 2/4 kind of sound. So I made up a new arrangement for it, changed it to 4/4, and added the little Bach-like intro on the 12-string. That made a difference.

Pete Seeger's 'Turn! Turn! Turn!' was your second Number 1. Why did you choose that song?

Pete Seeger was a hero of mine, and I'd recorded that song when I was working with Judy Collins on her third album. Later, I was on a bus tour with The Byrds and somebody asked if I knew the song. I started playing it and it came out in The Byrds' style, rather than Seeger's more legato style – and with different chords. I realised it sounded good, and we decided to record it. There was a big gulf between folk and rock at the time and a lot of the dyed-in-the-wool folkies didn't approve of what we were doing. There was an article by Tom Paxton in Sing Out! headlined 'Folk Rot'. The attitude was that we were subverting folk music and changing it in a bad way.

'Eight Miles High' introduced some of rock's first psychedelic guitar sounds. How come?

A friend of David Crosby had a copy of John Coltrane's latest album, which had that little melody line which we used for the opening lead guitar part in 'Eight Miles High'. We made a tape of it, listened to it over and over again on our tour bus, and by the time we got back to LA to start recording it was kind of ingrained. I'd been practising jazz and blues scales a lot so that just came out. Lyrically it was about the airplane ride over to England and the cultural shock we experienced when we got there. We were doing drugs, but 'Eight Miles High' wasn't a commercial for it. Some people put together the word 'high' with our appearance and came to a rather superficial conclusion.

Did the move away from folk rock contribute to you losing Gene Clark, one of the group's main songwriters?

Well, Gene refused to fly to a TV show in New York. He just got off the plane in LA, and that was it. Crosby was also getting a little bit antsy during the making of Fifth Dimension. He was worried that he wasn't getting enough of his own songs on the album.

Did you sack David Crosby because of his song 'Mind Gardens' on Younger Than Yesterday?

No, that had nothing to do with it. David just didn't like us any more. He didn't like to play with us. The day before we sacked him we had a rehearsal where he actually told us that we were not good enough to be playing with him.

Chris and I drove up to his house in twin Porsches to sack him? Yes, that's true. All four of us had Porsches. Mine was red, David's was blue, Chris's was black and Michael's was yellow. There was one wonderful day when the four of us were driving on Ventura Freeway in Los Angeles in a diamond formation at 80 miles an hour.

Despite shedding members, The Notorious Byrd Brothers didn't show any loss of innovation or songwriting quality.

That was a special album. It was kind of Beatles-inspired. I think they had Revolver out. Our producer Gary Usher was keen on the idea of letting tracks run into each other. He contributed a great deal to that album artistically, and even played on some tracks.

The country rock direction that you hear on a song like 'Old John Robertson' was always in the band. Chris had a real bluegrass background, and on Younger Than Yesterday he'd started writing songs like 'Time Between' and 'Girl With No Name'. 'John Robertson' was a very countryish thing, and I wrote a string quartet for the middle section which was another kind of eclectic element.

The full-blown country rock album, Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, was the product of a liaison with new member Gram Parsons. But wasn't it a difficult relationship?

He was good, but he wanted to steer The Byrds into country music exclusively and once I realised that, I didn't like it. He wanted the band to fire me and hire a steel guitar player.

Did the version of Dylan's 'You Ain't Going Nowhere' earn you a rebuke from Bob?

When we recorded that song, I switched around a line. I sang, "Pack up your money and pick up your tent" and it should have been "Pick up your money and pack up your tent". Bob doesn't like people messing around with his lyrics, so he recorded it the right way, and added my name after it, to clue me in that I'd screwed it up. It was a friendly jab. He and I are like brothers. Every time we meet it's like we've never been apart.

Does Dr. Byrds And Mr. Hyde stand the test of time?

It's kind of like we'd run out of gas. I do like 'Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man'. That was one of the best things that came from working with Gram. He and I wrote that in London. When we'd recorded 'You Ain't Going Nowhere', we took it to Ralph Emory at the major Nashville radio station WFM, and we asked him to play it on the air, but he didn't like it, and he refused to play it. So a couple of months later, Gram and I were sitting in a hotel room in London, and decided to write a song about Ralph, which was 'Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man'.

The title track of Ballad Of Easy Rider was written for the film Easy Rider. Were you aware that the leading characters in the film were based on yourself and Crosby?

The first time I saw it was in the recording studio, because I had to do a couple of songs for it. So I didn't see it all in one sitting, just disjointed scenes, and I didn't realise right off that it was based on myself and David. Peter [Fonda] told me that later. I said to him, "Man, I would have loved to have been in that movie." And Peter said, "You were." Peter is the generally optimistic character and Dennis Hopper is the paranoid hippy, which is exactly the relationship that Crosby and I had.

Was Byrdmaniax a low point?

Yeah. By that time the whole Byrds thing was falling apart. I became too democratic and allowed some of the other members to include songs that shouldn't really have got on there.

I wound up The Byrds and went solo after the original Byrds got back together for the ill-fated reunion album on Asylum. We were going to tour behind that, but it didn't do very well. It was a pretty good album, but it just didn't sell. I think people appreciate it more now. Becoming a solo act, really, was like going back to my original intention, to be a solo performer like Pete Seeger.

Your first solo album was a creative triumph, but didn't notch up any serious sales.

I was pleased with it, especially the things that are a little off the commercial track, like 'My New Woman' and 'Draggin''. I could have done 'Draggin'' better, I should have done it in a higher key, for example, which is how I do it in concert. I like 'I'm So Restless', with Dylan playing harmonica, and the production of 'Stone', with the kids' choir. It's a great song.

Were you as happy with Peace On You?

No. I had produced my first solo album, but it didn't sell well, so the record company dictated that I'd have a producer. They hired Bill Halverson who had done Crosby, Stills And Nash, assuming it would be a sure-fire combination, but it didn't work. I had no input into picking the material. I was just doing what I was told to do.

After that, we recorded the first McGuinn, Clark And Hillman album. It was a happy reunion, except that we had production problems again because the producers didn't want the 12-string Rickenbacker sound. And they didn't want me doing lead vocals, which sidelined me. Then they did a kind of disco-ish production, so I only got to do a couple of songs. I didn't have a lot of say in the matter. They were trying to achieve some commercial success and, from that aspect, it worked. We got a Top 40 hit.

Back From Rio was a renaissance. Why?

It's hard to define these things. I was writing things like 'King Of The Hill', with Tom Petty, and 'Someone To Love', with my wife, Camilla. Around then, The Traveling Wilburys were recording, and George [Harrison] invited me over to live at the house with them. If I'd done that, I would probably have been in the Wilburys, but I was busy doing my album, so it wasn't possible.

© Johnny Black, 2002

Tweet this Fact

Johnny Black, MOJO, September 2002

THE OPENING JINGLE-JANGLE 12-string Rickenbacker guitar line on The Byrds' 1965 classic, 'Mr Tambourine Man', ushered in a new era in popular music – the folk rock boom that spawned The Mamas And The Papas, Simon And Garfunkel, Fairport Convention and too many more to mention.

Not content with inventing one new genre, The Byrds were in the vanguard of so many emerging styles – from psychedelia to space rock, raga rock and country rock – that it seemed as if each successive album heralded a new epoch. And although many gifted musicians passed through the ranks, there was just one consistent factor throughout their entire career – the original techno-folkie, Roger McGuinn.

Now based in Florida, McGuinn continues to perform and record to considerable acclaim as a solo artist. His latest album, the Grammy-nominated Treasures From The Folk Den, explores his renewed love affair with the traditional folk songs that first inspired him, and he has recently toured the UK.

"Just me and two guitars – a Rickenbacker and an acoustic 12-string," he says. "I play a lot of traditional material, but I never forget that people want to hear The Byrds songs too, so I always do some of those too."

The earliest Byrds songs on record appear on Preflyte, but those weren't official recordings.

Those were really rehearsal tapes. Our manager Jim Dickson had access to the World Pacific Recording studio, and he offered it to us free if we'd go in after midnight when all the other sessions were closed down. He had old tapes that were all spliced together, not good enough for masters, and he let us practise with those. So we were just recording the tracks and listening back to see how we could improve them.

Did those demos prompt Miles Davis to get you signed to Columbia?

We never actually met Miles. His agent, Benny Shapiro, was a friend of Dickson's, so Gene Clark, David Crosby and I put a little backing tape together and went over to Benny's, and we sang with this tape in his living-room. Benny's teenage daughter was upstairs and when she heard us, she flipped out. She thought The Beatles were in her living room. The next day, Miles came by and Benny told him what had happened. Miles said, "Kids know stuff like that. You should pay attention." And on the strength of that Benny called up Columbia Records, which led to the deal.

Of all the available Dylan material, why did you pick 'Mr Tambourine Man' as the first Byrds single?

That was Dickson. He admired Dylan as a writer, so he'd been working with that and other Dylan songs in bluegrass with Vern Gosdin and Chris Hillman – who became The Byrds' bassist. 'Tambourine Man' was out as a demo but Columbia had shelved it because Ramblin' Jack Elliott was on the track and he was a bit inebriated, sounded a little out of tune, out of time. So Dickson had a copy sent out to LA from New York and we learned it. Initially, David Crosby didn't like it at all. He didn't like the sound of Dylan's voice. And by that point we were all getting into The Beatles, so David was a little down on folk music, and we wanted to do a Beatley kind of thing. We didn't want to do a folky 2/4 kind of sound. So I made up a new arrangement for it, changed it to 4/4, and added the little Bach-like intro on the 12-string. That made a difference.

Pete Seeger's 'Turn! Turn! Turn!' was your second Number 1. Why did you choose that song?

Pete Seeger was a hero of mine, and I'd recorded that song when I was working with Judy Collins on her third album. Later, I was on a bus tour with The Byrds and somebody asked if I knew the song. I started playing it and it came out in The Byrds' style, rather than Seeger's more legato style – and with different chords. I realised it sounded good, and we decided to record it. There was a big gulf between folk and rock at the time and a lot of the dyed-in-the-wool folkies didn't approve of what we were doing. There was an article by Tom Paxton in Sing Out! headlined 'Folk Rot'. The attitude was that we were subverting folk music and changing it in a bad way.

'Eight Miles High' introduced some of rock's first psychedelic guitar sounds. How come?

A friend of David Crosby had a copy of John Coltrane's latest album, which had that little melody line which we used for the opening lead guitar part in 'Eight Miles High'. We made a tape of it, listened to it over and over again on our tour bus, and by the time we got back to LA to start recording it was kind of ingrained. I'd been practising jazz and blues scales a lot so that just came out. Lyrically it was about the airplane ride over to England and the cultural shock we experienced when we got there. We were doing drugs, but 'Eight Miles High' wasn't a commercial for it. Some people put together the word 'high' with our appearance and came to a rather superficial conclusion.

Did the move away from folk rock contribute to you losing Gene Clark, one of the group's main songwriters?

Well, Gene refused to fly to a TV show in New York. He just got off the plane in LA, and that was it. Crosby was also getting a little bit antsy during the making of Fifth Dimension. He was worried that he wasn't getting enough of his own songs on the album.

Did you sack David Crosby because of his song 'Mind Gardens' on Younger Than Yesterday?

No, that had nothing to do with it. David just didn't like us any more. He didn't like to play with us. The day before we sacked him we had a rehearsal where he actually told us that we were not good enough to be playing with him.

Chris and I drove up to his house in twin Porsches to sack him? Yes, that's true. All four of us had Porsches. Mine was red, David's was blue, Chris's was black and Michael's was yellow. There was one wonderful day when the four of us were driving on Ventura Freeway in Los Angeles in a diamond formation at 80 miles an hour.

Despite shedding members, The Notorious Byrd Brothers didn't show any loss of innovation or songwriting quality.

That was a special album. It was kind of Beatles-inspired. I think they had Revolver out. Our producer Gary Usher was keen on the idea of letting tracks run into each other. He contributed a great deal to that album artistically, and even played on some tracks.

The country rock direction that you hear on a song like 'Old John Robertson' was always in the band. Chris had a real bluegrass background, and on Younger Than Yesterday he'd started writing songs like 'Time Between' and 'Girl With No Name'. 'John Robertson' was a very countryish thing, and I wrote a string quartet for the middle section which was another kind of eclectic element.

The full-blown country rock album, Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, was the product of a liaison with new member Gram Parsons. But wasn't it a difficult relationship?

He was good, but he wanted to steer The Byrds into country music exclusively and once I realised that, I didn't like it. He wanted the band to fire me and hire a steel guitar player.

Did the version of Dylan's 'You Ain't Going Nowhere' earn you a rebuke from Bob?

When we recorded that song, I switched around a line. I sang, "Pack up your money and pick up your tent" and it should have been "Pick up your money and pack up your tent". Bob doesn't like people messing around with his lyrics, so he recorded it the right way, and added my name after it, to clue me in that I'd screwed it up. It was a friendly jab. He and I are like brothers. Every time we meet it's like we've never been apart.

Does Dr. Byrds And Mr. Hyde stand the test of time?

It's kind of like we'd run out of gas. I do like 'Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man'. That was one of the best things that came from working with Gram. He and I wrote that in London. When we'd recorded 'You Ain't Going Nowhere', we took it to Ralph Emory at the major Nashville radio station WFM, and we asked him to play it on the air, but he didn't like it, and he refused to play it. So a couple of months later, Gram and I were sitting in a hotel room in London, and decided to write a song about Ralph, which was 'Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man'.

The title track of Ballad Of Easy Rider was written for the film Easy Rider. Were you aware that the leading characters in the film were based on yourself and Crosby?

The first time I saw it was in the recording studio, because I had to do a couple of songs for it. So I didn't see it all in one sitting, just disjointed scenes, and I didn't realise right off that it was based on myself and David. Peter [Fonda] told me that later. I said to him, "Man, I would have loved to have been in that movie." And Peter said, "You were." Peter is the generally optimistic character and Dennis Hopper is the paranoid hippy, which is exactly the relationship that Crosby and I had.

Was Byrdmaniax a low point?

Yeah. By that time the whole Byrds thing was falling apart. I became too democratic and allowed some of the other members to include songs that shouldn't really have got on there.

I wound up The Byrds and went solo after the original Byrds got back together for the ill-fated reunion album on Asylum. We were going to tour behind that, but it didn't do very well. It was a pretty good album, but it just didn't sell. I think people appreciate it more now. Becoming a solo act, really, was like going back to my original intention, to be a solo performer like Pete Seeger.

Your first solo album was a creative triumph, but didn't notch up any serious sales.

I was pleased with it, especially the things that are a little off the commercial track, like 'My New Woman' and 'Draggin''. I could have done 'Draggin'' better, I should have done it in a higher key, for example, which is how I do it in concert. I like 'I'm So Restless', with Dylan playing harmonica, and the production of 'Stone', with the kids' choir. It's a great song.

Were you as happy with Peace On You?

No. I had produced my first solo album, but it didn't sell well, so the record company dictated that I'd have a producer. They hired Bill Halverson who had done Crosby, Stills And Nash, assuming it would be a sure-fire combination, but it didn't work. I had no input into picking the material. I was just doing what I was told to do.

After that, we recorded the first McGuinn, Clark And Hillman album. It was a happy reunion, except that we had production problems again because the producers didn't want the 12-string Rickenbacker sound. And they didn't want me doing lead vocals, which sidelined me. Then they did a kind of disco-ish production, so I only got to do a couple of songs. I didn't have a lot of say in the matter. They were trying to achieve some commercial success and, from that aspect, it worked. We got a Top 40 hit.

Back From Rio was a renaissance. Why?

It's hard to define these things. I was writing things like 'King Of The Hill', with Tom Petty, and 'Someone To Love', with my wife, Camilla. Around then, The Traveling Wilburys were recording, and George [Harrison] invited me over to live at the house with them. If I'd done that, I would probably have been in the Wilburys, but I was busy doing my album, so it wasn't possible.

© Johnny Black, 2002