Fact #138579

When:

Short story:

Full article:

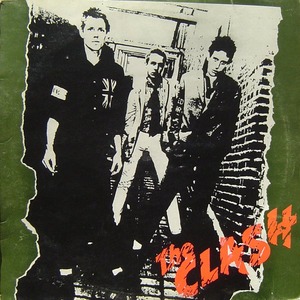

THE CLASH DEBUT ALBUM - THE CLASH

researched and written by Johnny Black, originally published in HiFi News.

Unusually, for an album awarded Vinyl Icon status, the fi of The Clash's eponymous debut is not of the highest. It is, however, an album which helped pioneer a radical change of thinking about the very nature and purpose of sound recordings.

The general thrust of progress in studio recording throughout the 20th century was about capturing sound with ever-improving fidelity. Occasional albums refused to play ball, notoriously 1968's White Light White Heat by The Velvet Underground, which was deliberately recorded with the VU meter needles jammed firmly into the red to simulate the dirty, distorted sound the band strived for on stage.

Nevertheless, by the mid-70s, musicians and producers would routinely strive for days to achieve, for example, a 'perfect' drum sound or a 'perfect' mix of 24 separate tracks on a three-minute pop single.

To many rock fans, it seemed as if this modus operandi was sometimes to the detriment of the music itself, resulting in antiseptic recordings which lacked passion. Punk rock provided one possible alternative – work fast, capture the energy of live performance, the spirit of the song and the passion of the performers. In this respect, The Clash's debut is a landmark. "We were very keen that it didn't become over-produced," Joe Strummer later told journalist Mal Peachy, "We didn't want to get compromised by the sound."

Like many punk albums, The Clash is more a social document, inspired by and commenting on the events of the time, than it is a perfect audio recording.

The song White Riot, for example, was guitarist/singer Joe Strummer's account of finding himself in the middle of a riot during London's Notting Hill Carnival on August 30, 1976. "Cop cars were speeding through, these Rover 2000s, and they were being pelted with rocks and cobblestones and cans as they came through. It was like a bowling alley," he recalled later.

Career Opportunities was a howl of rage against the unemployment figures in England at the time, and Remote Control included caustic observations about the small-town bureaucrats who were cancelling punk rock concerts on any excuse.

Although work on what eventually became their epochal debut album was started on February 10, 1977, at CBS Studios in Whitfield Street, London, The Clash had already demoed five songs – White Riot, Janie Jones, Career Opportunities, London's Burning and 1977 – three months earlier at Polydor Studios, 17 Stratford Place, just off Oxford Street.

Polydor A+R man Chris Parry, later to sign The Cure, had failed to clinch a deal for The Sex Pistols and was now hoping to get The Clash onto his label.

Parry brought in name producer Guy Stevens, famed for his work with Free and Mott The Hoople, but unfortunately Stevens was becoming increasingly erratic and unreliable due to his fondness for drink and drugs.

Clash guitarist Mick Jones told Zigzag magazine in April 1977, that, "It was great recording with Guy Stevens … fantastic when we were doing it. He was really inciting us but, when it came down to the mixing, it was a bit untogether."

Polydor passed on The Clash who then negotiated a deal with CBS and started work on the album in early February 1977.

The band at this point comprised Joe Strummer, (guitars/vocals), Mick Jones (guitars/vocals) and Paul Simonon (bass). The drum stool was filled by Terry Chimes who, even though he had officially quit the group some weeks earlier, agreed to play on the album as they had rehearsed most of the songs with him.

Steve Levine, now one of the UK's most celebrated producers (Culture Club, Beach Boys etc), was in a rather more humble job back then. "I was the tape-op, and I remember the first weekend when The Clash came in extremely well," he tells me. "Simon Humphrey who was slightly more senior was the engineer, and they came down to do the initial bunch of tracks."

Humphrey remembers a somewhat chilly start to proceedings. "They wouldn't shake my hand because I was a hippy."

CBS was, apparently, so baffled by The Clash's desire not "to get compromised by the sound" that they decided against employing a top-flight producer and, as Humphrey has recalled they, "never showed their faces at all during the recording of the album. They kept well away. I was given carte blanche to let them go in and do what they wanted."

As a result, The Clash's live sound man Micky Foote was designated as producer and his philosophy was exactly in line with the band's. "It was a matter of go in, set up and keep the overdubs to the minimum," he said later. "The album couldn't have been done any other way."

Nor did it help that the band was far from reliable when it came to time-keeping. "There was a rivalry between Mick and Joe," points out Humphrey. "One of them would turn up and say, 'Who else is here?' And I'd say, 'Actually, Mick, you're the first one.' He'd say, 'F**k that!' and bugger off. Then Joe would turn up and say, 'Where's Mick?' And I would say, 'He was here earlier, but he left.' So Joe would say, 'Bloody hell!' and storm off. Then they'd all reconvene later on."

When they did finally all manage to get in the studio together, "We'd play a song, have a quick break, then play the next one, shout at each other and then do another song," revealed Mick Jones to John Robb in his book Punk Rock – An Oral History. "Joe would give me the words and I would make a song out of them. The words would have such a great rhythm to them. Everything would come together really, really fast."

The album kicks off with Janie Jones, a song about a famous British madam, which had popped into Mick Jones's head while he was on the No31 bus from Harrow Road to the band's rehearsal space in Chalk Farm. Legendary film maker Martin Scorsese would later use the song in his 1999 film Bringing Out The Dead and has described it as "the greatest British rock and roll song."

Another song that started with Mick was I'm So Bored With The USA, but it was Strummer who gave it it's political bite. The Jones version was about his girlfriend (also the subject of Deny) but, as Strummer told journalist Jon Savage, "Mick had this riff, and I thought he’d said I’m So Bored With The USA, I jumped up, said, 'That’s great. Let’s write some lyrics.' He said, 'Its not that, its I’m So Bored With You.' In Strummer's hands the song became a rant against the state of American society – everything from Watergate to tv shows to drug problems in the US Army.

For Cheat, written in November 1976, Strummer simplified the Situationist slogan "In order to survive, we steal, cheat, lie, forge, deal, hide and kill" by singing "I have the will to survive, I cheat if I can't win", but not all of the songs are so overtly political.

48 Hours, written in the band's Camden rehearsal studio, is a relatively straightforward hymn to the delights of the weekend, and the subject of Protex Blue is nothing more than a brand of condom available from the dispenser in the Windsor Castle pub near Mick's flat.

The album's closer, Garageland, was Strummer's angry riposte to a review written by Charles Shaar Murray of the NME. Murray had seen them play at Islington's Screen On the Green and described them as "the kind of garage band who should be speedily returned to their garage, preferably with the engine running". Stung, Strummer, hit back with this song.

Perhaps the biggest surprise on the album was Police And Thieves, a cover of a Junior Murvin and Lee Perry reggae track. As Strummer told Caroline Coon, "It was just a wild idea I had one night … I wanted to do a Hawkwind version of a song that was familiar to us, and we just did it within our limitations."

It's worth remembering, though, that this was long before The Police, Culture Club or Eurythmics had dabbled with blending rock and reggae, and provides another example of just how radical this album was for its time.

As Steve Levine remembers, "They were exciting and vibrant to work with. Like all those bands, because I also did The Vibrators, The Drones … every single band that came in was really exciting."

The album was completed on February 27, and hit the streets on April 8.

"As a debut, it's frighteningly assured," reckoned Pete Silverton in Sounds. "If you don't like The Clash, you don't like rock'n'roll. It really is as simple as that. Period."

Although cheaply and quickly recorded, it went on to influence a generation of future stars and still appears regularly in all-time greatest album lists. In March 2003, for example, Mojo magazine ranked The Clash number 2 in its "Top 50 Punk Albums", and lauded it as "the ultimate punk protest album".

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PRODUCTION NOTES

THE CLASH – THE CLASH

Long-since demolished, the CBS premises in Whitfield Street, just off London's Tottenham Court Road, housed three studios whose claims to fame in 1977 included sessions by Supertramp, Mott The Hoople, Iggy And the Stooges and more. Studio three was the smallest, a tiny room on the top floor with 16-track analogue recording decks.

"They had this great system at CBS," remembers Steve Levine, who was a tape-op in 1977. "The junior engineers and the demo bands were given time in Studio 3, which housed all the old gear that had previously been in Studios 1 and 2. It was great because firstly, we were still learning our craft as engineers, and those bands were the same age as us."

Before punk kicked in, says Levine, "you used to have those AOR sessions, where bands would spend days just trying to get a snare drum sound. I remember walking past Studio 2 when Supertramp were in there for a while and all I ever heard was the sound of the snare drum, no matter what time of day it was."

The poorly equipped Studio 3 might seem a curious choice for first album sessions by a band which had been signed for a reported £100,000 but its Spartan ambiance fitted well with The Clash's punk ethic. "I recall the place being cramped and somewhat archaic," remembered Zigzag writer Kris Needs, who had become friendly with the band. "It was like CBS had shoved this bunch of punks into the cupboard where they could be heard and not seen. Or as Joe put it, 'I got the feeling they were going to spend the price of an egg sandwich on us.'"

In the end, the three weeks of sporadic sessions came in at around £4000, cheap even then.

Levine reveals to me exactly what the highly-trained CBS staff were up against. "When Strummer came in to Studio 3 for the first time, he saw that we had put some screens up round the guitar amps and he said, "What are they?" So I explained they would allow us to separate the sound of the guitars and the bass a little bit. And Joe said, 'I dunno what separation is, but I don't like it.'" Fuelled, in those days, by considerable amounts of speed washed down with Special Brew, Strummer was not a man to be argued with.

Strummer's battered old 1966 Fender Telecaster was held together largely by gaffa tape, so CBS pitched in by acquiring a brand new fender for him, which he resolutely refused to touch.

After years of fronting pub-rock band The 101ers, Stummer found it impossible to sing without strumming his guitar, so his Telecaster was left unplugged for most of the sessions.

Even so, Strummer felt The Clash got what they wanted out of Studio 3. As he told journalist Caroline Coon, "When we went into the studio as far as we're concerned it was technically perfect. There may have been a few bum notes but if the whole track sounded good we let them go."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

FURTHER QUOTES ABOUT THE CLASH DEBUT LP

Joe Strummer (The Clash) : Terry [drummer Terry Chimes] wanted to join a pop group and get a Lamborghini, your average suburban kid's dream, right? And we used to have discussions, we were quite rigorous, and when he said this about the Lamborghini, it was heresy! We were laughing and jeering at him, and he took it very seriously, and one day he just didn't show up for rehearsals. He phoned up and said he quit. But he was cool enough to come and do the album with us, cos we'd rehearsed the numbers with him. (Source : unpublished interview with Jon Savage, 1988)

Mick Jones (The Clash) : I was so into speed I don't even recall making the first album.

Simon Humphrey (engineer) : They wouldn't shake my hand because I was a hippy. There was a rivalry between Mick and Joe. One of them would turn up and say, 'Who else is here?' And I'd say, 'Actually, Mick, you're the first one.' He'd say, 'Fuck that!' and bugger off. Then Joe would turn up and say, 'Where's Mick?' And I would say, 'He was here earlier, but he left.' So Joe would say, 'Bloody hell!' and storm off. Then they'd all reconvene later on.

Keith Levene (guitarist, The Clash, but left before recording of the album started) : Mick had the main body, the foundation of the songs. The one tune that I totally wrote on my own was What's My Name. That's when I mastered how to write a song. "Oh, that's how you do it? It's so easy!" The credits they gave me on the album... I didn't play at all on the album but they credited me for some reason for What's My Name as a third credit. And they didn't credit me on anything else. And I wrote a lot of that other stuff. I contributed to it. Those songs wouldn't sound they way they did if I hadn't contributed to them. I didn't contribute that much to 1977 and White Riot 'cause those are the things we literally split up over. But all the other stuff I did. I should have at least gotten a third credit on the other tunes and full credit on What's My Name. And they've never paid me for it either.

Steve Levine (CBS Tape-op) : They had this great system at CBS where the junior engineers and the demo bands were given time in Studio 3, which housed all the old gear that had previously been in Studios 1 and 2. It was great because the bands we got in Studio 3 were the same sort of age as us.

I remember the first weekend when The Clash came in extremely well. I was the tape-op, me and Simon Humphrey who was slightly more senior, and they came down to do the initial bunch of tracks.

On that first album with The Clash, 99.9% of the tracks were done in Studio 3, and even a few things after that as well. Simon and I never got credits on those things though, so very few people knew we had done it.

For those initial sessions Micky Foote, their live sound guy, was kind of the official designated producer but, to be honest, he didn't do that much.

Mickey Foote : It was a matter of go in, set up and keep the overdubs to the minimum. The album couldn't have been done any other way.

Mick Jones : We'd play a song, have a quick break, then play the next one, shout at each other and then do another song. Joe would give me the words and I would make a song out of them. The words would have such a great rhythm to them. Everything would come together really, really fast.

(Source : Punk Rock – An Oral History by John Robb, Ebury Press, 2006)

Simon Humphrey : The record company never showed their faces at all during the recording of the single or the album. They kept well away. I was given carte blanche to let them go in and do what they wanted.

(Source : The Last Gang In Town by Marcus Gray, 1995)

Steve Levine : They were exciting and vibrant to work with. Like all those bands, because I also did The Vibrators, The Drones, every single band that came in was really exciting because, firstly, we were still learning our craft as engineers.

Then there were a few occasions when we doubled up, before they left CBS to work with Bill Price and all of that. Some of the b-sides we split up so that, for example, Simon Humphrey was up in Studio 3 with Joe Strummer while I was down in Studio 2 with Mick Jones. One of the last tracks that we did was White Man In Hammersmith Palais, which was definitely split between the two studios.

(Source : interview with Johnny Black for Music Week, May 2010)

Joe Strummer : We were very keen that it didn't become over-produced. We didn't want to get compromised by the sound.

(Source : interview with Mal Peachy, date unknown)

Joe Strummer (about I'm So Bored With The USA) : I’d gone to the squat in Shepherd’s Bush, and Mick had this riff, and I thought he’d said I’m So Bored With The USA, I jumped up, said that’s great. Let’s write some lyrics. He said, its not that, its I’m So Bored With You. But he agreed that USA was much better. It was more interesting. When Mick wrote it, it was a love song. But I thought it was more interesting, cos Kojak and all that stuff was big at the time. Columbo. That lyric’s not bad, even now, although its cave man primitive, it says a lot of truth, about the dictators, yankee dollar talk to the dictators of the world.

(Unpublished interview with Jon Savage at http://fromtheothersideofthemirror.com/2009/06/03/unpublished-joe-strummer-interview/)

Joe Strummer (about Police And Thieves) : It was just a wild idea I had one night. I wanted to play reggae when the band first started but I was talked out of it. Rightly so. There's people like Rotten who say, "I'd never play reggae". And he says that because he's got too much sense. I mean, who wants to sound like G.T. Moore and the Reggae Guitars!

And we can't really play reggae. Who the hell could play them reggae drums apart from a black man? But I wanted to do a Hawkwind version of a song that was familiar to us, and we just did it within our limitations. If it had sounded shitty we'd have dropped it. But it sounded great. There's hardly any reggae in it at all – just a few offbeat guitars thrown in for a laugh – it's all rock'n'roll. I think it's an incredible track.

(Source : interview with Caroline Coon, 1977)

Sharleen Spiteri (on buying a guitar to play in her new band, Texas) :I knew exactly what I wanted: a black-and-white Telecaster. For me, The Clash have always been the ultimate rock'n'roll band.

Tweet this Fact

researched and written by Johnny Black, originally published in HiFi News.

Unusually, for an album awarded Vinyl Icon status, the fi of The Clash's eponymous debut is not of the highest. It is, however, an album which helped pioneer a radical change of thinking about the very nature and purpose of sound recordings.

The general thrust of progress in studio recording throughout the 20th century was about capturing sound with ever-improving fidelity. Occasional albums refused to play ball, notoriously 1968's White Light White Heat by The Velvet Underground, which was deliberately recorded with the VU meter needles jammed firmly into the red to simulate the dirty, distorted sound the band strived for on stage.

Nevertheless, by the mid-70s, musicians and producers would routinely strive for days to achieve, for example, a 'perfect' drum sound or a 'perfect' mix of 24 separate tracks on a three-minute pop single.

To many rock fans, it seemed as if this modus operandi was sometimes to the detriment of the music itself, resulting in antiseptic recordings which lacked passion. Punk rock provided one possible alternative – work fast, capture the energy of live performance, the spirit of the song and the passion of the performers. In this respect, The Clash's debut is a landmark. "We were very keen that it didn't become over-produced," Joe Strummer later told journalist Mal Peachy, "We didn't want to get compromised by the sound."

Like many punk albums, The Clash is more a social document, inspired by and commenting on the events of the time, than it is a perfect audio recording.

The song White Riot, for example, was guitarist/singer Joe Strummer's account of finding himself in the middle of a riot during London's Notting Hill Carnival on August 30, 1976. "Cop cars were speeding through, these Rover 2000s, and they were being pelted with rocks and cobblestones and cans as they came through. It was like a bowling alley," he recalled later.

Career Opportunities was a howl of rage against the unemployment figures in England at the time, and Remote Control included caustic observations about the small-town bureaucrats who were cancelling punk rock concerts on any excuse.

Although work on what eventually became their epochal debut album was started on February 10, 1977, at CBS Studios in Whitfield Street, London, The Clash had already demoed five songs – White Riot, Janie Jones, Career Opportunities, London's Burning and 1977 – three months earlier at Polydor Studios, 17 Stratford Place, just off Oxford Street.

Polydor A+R man Chris Parry, later to sign The Cure, had failed to clinch a deal for The Sex Pistols and was now hoping to get The Clash onto his label.

Parry brought in name producer Guy Stevens, famed for his work with Free and Mott The Hoople, but unfortunately Stevens was becoming increasingly erratic and unreliable due to his fondness for drink and drugs.

Clash guitarist Mick Jones told Zigzag magazine in April 1977, that, "It was great recording with Guy Stevens … fantastic when we were doing it. He was really inciting us but, when it came down to the mixing, it was a bit untogether."

Polydor passed on The Clash who then negotiated a deal with CBS and started work on the album in early February 1977.

The band at this point comprised Joe Strummer, (guitars/vocals), Mick Jones (guitars/vocals) and Paul Simonon (bass). The drum stool was filled by Terry Chimes who, even though he had officially quit the group some weeks earlier, agreed to play on the album as they had rehearsed most of the songs with him.

Steve Levine, now one of the UK's most celebrated producers (Culture Club, Beach Boys etc), was in a rather more humble job back then. "I was the tape-op, and I remember the first weekend when The Clash came in extremely well," he tells me. "Simon Humphrey who was slightly more senior was the engineer, and they came down to do the initial bunch of tracks."

Humphrey remembers a somewhat chilly start to proceedings. "They wouldn't shake my hand because I was a hippy."

CBS was, apparently, so baffled by The Clash's desire not "to get compromised by the sound" that they decided against employing a top-flight producer and, as Humphrey has recalled they, "never showed their faces at all during the recording of the album. They kept well away. I was given carte blanche to let them go in and do what they wanted."

As a result, The Clash's live sound man Micky Foote was designated as producer and his philosophy was exactly in line with the band's. "It was a matter of go in, set up and keep the overdubs to the minimum," he said later. "The album couldn't have been done any other way."

Nor did it help that the band was far from reliable when it came to time-keeping. "There was a rivalry between Mick and Joe," points out Humphrey. "One of them would turn up and say, 'Who else is here?' And I'd say, 'Actually, Mick, you're the first one.' He'd say, 'F**k that!' and bugger off. Then Joe would turn up and say, 'Where's Mick?' And I would say, 'He was here earlier, but he left.' So Joe would say, 'Bloody hell!' and storm off. Then they'd all reconvene later on."

When they did finally all manage to get in the studio together, "We'd play a song, have a quick break, then play the next one, shout at each other and then do another song," revealed Mick Jones to John Robb in his book Punk Rock – An Oral History. "Joe would give me the words and I would make a song out of them. The words would have such a great rhythm to them. Everything would come together really, really fast."

The album kicks off with Janie Jones, a song about a famous British madam, which had popped into Mick Jones's head while he was on the No31 bus from Harrow Road to the band's rehearsal space in Chalk Farm. Legendary film maker Martin Scorsese would later use the song in his 1999 film Bringing Out The Dead and has described it as "the greatest British rock and roll song."

Another song that started with Mick was I'm So Bored With The USA, but it was Strummer who gave it it's political bite. The Jones version was about his girlfriend (also the subject of Deny) but, as Strummer told journalist Jon Savage, "Mick had this riff, and I thought he’d said I’m So Bored With The USA, I jumped up, said, 'That’s great. Let’s write some lyrics.' He said, 'Its not that, its I’m So Bored With You.' In Strummer's hands the song became a rant against the state of American society – everything from Watergate to tv shows to drug problems in the US Army.

For Cheat, written in November 1976, Strummer simplified the Situationist slogan "In order to survive, we steal, cheat, lie, forge, deal, hide and kill" by singing "I have the will to survive, I cheat if I can't win", but not all of the songs are so overtly political.

48 Hours, written in the band's Camden rehearsal studio, is a relatively straightforward hymn to the delights of the weekend, and the subject of Protex Blue is nothing more than a brand of condom available from the dispenser in the Windsor Castle pub near Mick's flat.

The album's closer, Garageland, was Strummer's angry riposte to a review written by Charles Shaar Murray of the NME. Murray had seen them play at Islington's Screen On the Green and described them as "the kind of garage band who should be speedily returned to their garage, preferably with the engine running". Stung, Strummer, hit back with this song.

Perhaps the biggest surprise on the album was Police And Thieves, a cover of a Junior Murvin and Lee Perry reggae track. As Strummer told Caroline Coon, "It was just a wild idea I had one night … I wanted to do a Hawkwind version of a song that was familiar to us, and we just did it within our limitations."

It's worth remembering, though, that this was long before The Police, Culture Club or Eurythmics had dabbled with blending rock and reggae, and provides another example of just how radical this album was for its time.

As Steve Levine remembers, "They were exciting and vibrant to work with. Like all those bands, because I also did The Vibrators, The Drones … every single band that came in was really exciting."

The album was completed on February 27, and hit the streets on April 8.

"As a debut, it's frighteningly assured," reckoned Pete Silverton in Sounds. "If you don't like The Clash, you don't like rock'n'roll. It really is as simple as that. Period."

Although cheaply and quickly recorded, it went on to influence a generation of future stars and still appears regularly in all-time greatest album lists. In March 2003, for example, Mojo magazine ranked The Clash number 2 in its "Top 50 Punk Albums", and lauded it as "the ultimate punk protest album".

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PRODUCTION NOTES

THE CLASH – THE CLASH

Long-since demolished, the CBS premises in Whitfield Street, just off London's Tottenham Court Road, housed three studios whose claims to fame in 1977 included sessions by Supertramp, Mott The Hoople, Iggy And the Stooges and more. Studio three was the smallest, a tiny room on the top floor with 16-track analogue recording decks.

"They had this great system at CBS," remembers Steve Levine, who was a tape-op in 1977. "The junior engineers and the demo bands were given time in Studio 3, which housed all the old gear that had previously been in Studios 1 and 2. It was great because firstly, we were still learning our craft as engineers, and those bands were the same age as us."

Before punk kicked in, says Levine, "you used to have those AOR sessions, where bands would spend days just trying to get a snare drum sound. I remember walking past Studio 2 when Supertramp were in there for a while and all I ever heard was the sound of the snare drum, no matter what time of day it was."

The poorly equipped Studio 3 might seem a curious choice for first album sessions by a band which had been signed for a reported £100,000 but its Spartan ambiance fitted well with The Clash's punk ethic. "I recall the place being cramped and somewhat archaic," remembered Zigzag writer Kris Needs, who had become friendly with the band. "It was like CBS had shoved this bunch of punks into the cupboard where they could be heard and not seen. Or as Joe put it, 'I got the feeling they were going to spend the price of an egg sandwich on us.'"

In the end, the three weeks of sporadic sessions came in at around £4000, cheap even then.

Levine reveals to me exactly what the highly-trained CBS staff were up against. "When Strummer came in to Studio 3 for the first time, he saw that we had put some screens up round the guitar amps and he said, "What are they?" So I explained they would allow us to separate the sound of the guitars and the bass a little bit. And Joe said, 'I dunno what separation is, but I don't like it.'" Fuelled, in those days, by considerable amounts of speed washed down with Special Brew, Strummer was not a man to be argued with.

Strummer's battered old 1966 Fender Telecaster was held together largely by gaffa tape, so CBS pitched in by acquiring a brand new fender for him, which he resolutely refused to touch.

After years of fronting pub-rock band The 101ers, Stummer found it impossible to sing without strumming his guitar, so his Telecaster was left unplugged for most of the sessions.

Even so, Strummer felt The Clash got what they wanted out of Studio 3. As he told journalist Caroline Coon, "When we went into the studio as far as we're concerned it was technically perfect. There may have been a few bum notes but if the whole track sounded good we let them go."

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

FURTHER QUOTES ABOUT THE CLASH DEBUT LP

Joe Strummer (The Clash) : Terry [drummer Terry Chimes] wanted to join a pop group and get a Lamborghini, your average suburban kid's dream, right? And we used to have discussions, we were quite rigorous, and when he said this about the Lamborghini, it was heresy! We were laughing and jeering at him, and he took it very seriously, and one day he just didn't show up for rehearsals. He phoned up and said he quit. But he was cool enough to come and do the album with us, cos we'd rehearsed the numbers with him. (Source : unpublished interview with Jon Savage, 1988)

Mick Jones (The Clash) : I was so into speed I don't even recall making the first album.

Simon Humphrey (engineer) : They wouldn't shake my hand because I was a hippy. There was a rivalry between Mick and Joe. One of them would turn up and say, 'Who else is here?' And I'd say, 'Actually, Mick, you're the first one.' He'd say, 'Fuck that!' and bugger off. Then Joe would turn up and say, 'Where's Mick?' And I would say, 'He was here earlier, but he left.' So Joe would say, 'Bloody hell!' and storm off. Then they'd all reconvene later on.

Keith Levene (guitarist, The Clash, but left before recording of the album started) : Mick had the main body, the foundation of the songs. The one tune that I totally wrote on my own was What's My Name. That's when I mastered how to write a song. "Oh, that's how you do it? It's so easy!" The credits they gave me on the album... I didn't play at all on the album but they credited me for some reason for What's My Name as a third credit. And they didn't credit me on anything else. And I wrote a lot of that other stuff. I contributed to it. Those songs wouldn't sound they way they did if I hadn't contributed to them. I didn't contribute that much to 1977 and White Riot 'cause those are the things we literally split up over. But all the other stuff I did. I should have at least gotten a third credit on the other tunes and full credit on What's My Name. And they've never paid me for it either.

Steve Levine (CBS Tape-op) : They had this great system at CBS where the junior engineers and the demo bands were given time in Studio 3, which housed all the old gear that had previously been in Studios 1 and 2. It was great because the bands we got in Studio 3 were the same sort of age as us.

I remember the first weekend when The Clash came in extremely well. I was the tape-op, me and Simon Humphrey who was slightly more senior, and they came down to do the initial bunch of tracks.

On that first album with The Clash, 99.9% of the tracks were done in Studio 3, and even a few things after that as well. Simon and I never got credits on those things though, so very few people knew we had done it.

For those initial sessions Micky Foote, their live sound guy, was kind of the official designated producer but, to be honest, he didn't do that much.

Mickey Foote : It was a matter of go in, set up and keep the overdubs to the minimum. The album couldn't have been done any other way.

Mick Jones : We'd play a song, have a quick break, then play the next one, shout at each other and then do another song. Joe would give me the words and I would make a song out of them. The words would have such a great rhythm to them. Everything would come together really, really fast.

(Source : Punk Rock – An Oral History by John Robb, Ebury Press, 2006)

Simon Humphrey : The record company never showed their faces at all during the recording of the single or the album. They kept well away. I was given carte blanche to let them go in and do what they wanted.

(Source : The Last Gang In Town by Marcus Gray, 1995)

Steve Levine : They were exciting and vibrant to work with. Like all those bands, because I also did The Vibrators, The Drones, every single band that came in was really exciting because, firstly, we were still learning our craft as engineers.

Then there were a few occasions when we doubled up, before they left CBS to work with Bill Price and all of that. Some of the b-sides we split up so that, for example, Simon Humphrey was up in Studio 3 with Joe Strummer while I was down in Studio 2 with Mick Jones. One of the last tracks that we did was White Man In Hammersmith Palais, which was definitely split between the two studios.

(Source : interview with Johnny Black for Music Week, May 2010)

Joe Strummer : We were very keen that it didn't become over-produced. We didn't want to get compromised by the sound.

(Source : interview with Mal Peachy, date unknown)

Joe Strummer (about I'm So Bored With The USA) : I’d gone to the squat in Shepherd’s Bush, and Mick had this riff, and I thought he’d said I’m So Bored With The USA, I jumped up, said that’s great. Let’s write some lyrics. He said, its not that, its I’m So Bored With You. But he agreed that USA was much better. It was more interesting. When Mick wrote it, it was a love song. But I thought it was more interesting, cos Kojak and all that stuff was big at the time. Columbo. That lyric’s not bad, even now, although its cave man primitive, it says a lot of truth, about the dictators, yankee dollar talk to the dictators of the world.

(Unpublished interview with Jon Savage at http://fromtheothersideofthemirror.com/2009/06/03/unpublished-joe-strummer-interview/)

Joe Strummer (about Police And Thieves) : It was just a wild idea I had one night. I wanted to play reggae when the band first started but I was talked out of it. Rightly so. There's people like Rotten who say, "I'd never play reggae". And he says that because he's got too much sense. I mean, who wants to sound like G.T. Moore and the Reggae Guitars!

And we can't really play reggae. Who the hell could play them reggae drums apart from a black man? But I wanted to do a Hawkwind version of a song that was familiar to us, and we just did it within our limitations. If it had sounded shitty we'd have dropped it. But it sounded great. There's hardly any reggae in it at all – just a few offbeat guitars thrown in for a laugh – it's all rock'n'roll. I think it's an incredible track.

(Source : interview with Caroline Coon, 1977)

Sharleen Spiteri (on buying a guitar to play in her new band, Texas) :I knew exactly what I wanted: a black-and-white Telecaster. For me, The Clash have always been the ultimate rock'n'roll band.