Fact #117366

When:

Short story:

Full article:

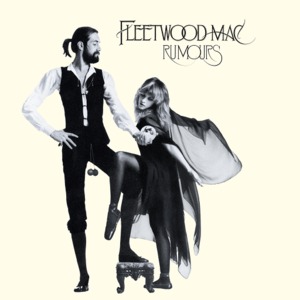

Fleetwood Mac – Rumours

Catalogue Number : Warner Bros K56344

The staggering sales figures – it went platinum within a month of release and is now fast-approaching 20 times platinum - reveal only a small part of the significance of Rumours in rock history.

Technically, this classic album pushed production standards up to new levels, and musically it raised the stakes in terms of song quality, performance and meticulous attention to detail. It was also the album where the artists’ real lives became virtually indistinguishable from the songs they were singing.

This had happened before, with the Mamas And Papas, and it would happen again with Abba, but Rumours was the moment when the phenomenon of confessional pop song writing really captured the imagination of the record-buying public.

Fleetwood Mac had started life as a mid-60s British r’nb quintet and had the competition beaten hollow until their brilliant songwriter-guitarist went off the rails on LSD. Re-locating to California, the Mac noodled around inconsequentially for several years until drummer Mick Fleetwood heard the album Buckingham-Nicks by aspiring songwriters Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks.

Fleetwood invited them to join the band and the first album with this new line-up took off like a rocket. On 15 February 1976, they began recording the follow-up, Rumours, at the Record Plant, Sausalito, California, USA.

“The Record Plant was this amazing hippy place,” recalls Stevie Nicks. “We like to say we were all hippies but, in the beginning, we really weren’t. But we went up to this incredible studio, which was all decorated with Indian saris and beautiful colours, there were little hippy girls everywhere making cookies … it was such a beautiful thing. You walked in and you were like, ‘Aaaaah! I love this place.”

Regrettably, however, the Mac had brought their own snakes into this hippy garden of paradise, because the two romantic relationships in the band, Buckingham-Nicks and John and Christine McVie, were rapidly disintegrating. The first thing they had to do was work out how to continue functioning as professionals when their personal lives had become seething cauldrons of disappointment, mistrust and anger. “There was pain, there was confusion,” says Buckingham, “and it all added up to make Rumours a soap opera on vinyl.”

The band aid they used to patch over their open sores was work. “We had two alternatives,” explains Christine McVie. “Go our own ways and see the band collapse, or grit our teeth and carry on playing with each other. Normally, when couples split they don’t have to see each other again. We were forced to get over those differences.” This need to maintain the band’s stability trapped them in an environment where they were precluded from publicly, or even privately, expressing their true feelings. Almost inevitably, their unspeakable despair found its way into the songs.

Bassist John McVie was not a songwriter, so Christine’s eloquently regretful reflections on their crumbling marriage, Songbird and Oh Daddy, have no response from him. “I’d be sitting there in the studio while they were mixing Don’t Stop,” he reflects, “and I’d listen to the words, which were mostly about me, and I’d get a lump in my throat. I’d turn around and the writer’s sitting right there.”

Buckingham and Nicks, however, were both songwriters, and their compositions effectively became substitutes for conversations they should have been having.

“When we were writing and recording these songs,” says Nicks, “I don’t think we really thought about what the lyrics were saying. It was only later down the line that Lindsey did come to question the lyric of my song Dreams, and my answer was that it was my counterpart to Go Your Own Way.”

“The spark for that song,” admits Buckingham, “was that Stevie and I were crumbling. It was totally autobiographical.”

Mick Fleetwood remembers Stevie being particularly upset by the words ‘crackin’ up, shackin’ up’ being directed at her by Lindsey through his song. For her part, Nicks felt that Dreams was much more empathetic than Go Your Own Way. “In my heart,” she told him, “Dreams was open and hopeful, but in Go Your Own Way, your heart was closed.”

As well as their personal problems, they soon found that the Record Plant was a strange place in which to work. There was a sunken pit in one of the studios, known as Sly Stone’s pit, which Fleetwood remembers as being, “usually occupied by people we didn’t know, tapping razors on mirrors.”

Cris Morris, the engineer who had helped build the record Plant, points out that, “A lot of other musicians dropped by. Van Morrison hung out a lot. Rufus and Chaka Khan, Rick James…”

It wasn’t long, though, before Fleetwood Mac, who were now reaping huge financial benefits of the success of their previous album, found themselves indulging in narcotic recreational pursuits. “It was the craziest period of our lives,” says Fleetwood. “We went four or five weeks without sleep, doing a lot of drugs. I’m talking about cocaine in such quantities that, at one point I thought I was really going insane.”

Somehow, though, ground-breaking work continued to get done. In the powerfully driving Don’t Stop, for example, the voices of Buckingham and McVie were deliberately equalized and compressed to such an extent that they sounded almost identical. “We were trying to get unique sounds on every instrument,” remembers Morris. “We spent ten solid hours on a kick drum sound in Studio B. Eventually we moved into Studio A and built a special platform for the drums, which got them sounding the way we wanted.”

Although the basic tracks were completed in Sausalito, there was a further period of several months in Los Angeles, largely given over to mixing plus vocal, guitar and percussion overdubs.

“Looking back at it from 56 years old,” says Nicks, “all I can think is ‘Thank god it wasn’t worse’. Thank god we didn’t get into heroin. We were lucky that we were always able to get ourselves together to make the music. Maybe it was the music that saved all of us.”

(Source : written by Johnny Black, first appeared in the book Albums, Backbeat, 2006)

Tweet this Fact

Catalogue Number : Warner Bros K56344

The staggering sales figures – it went platinum within a month of release and is now fast-approaching 20 times platinum - reveal only a small part of the significance of Rumours in rock history.

Technically, this classic album pushed production standards up to new levels, and musically it raised the stakes in terms of song quality, performance and meticulous attention to detail. It was also the album where the artists’ real lives became virtually indistinguishable from the songs they were singing.

This had happened before, with the Mamas And Papas, and it would happen again with Abba, but Rumours was the moment when the phenomenon of confessional pop song writing really captured the imagination of the record-buying public.

Fleetwood Mac had started life as a mid-60s British r’nb quintet and had the competition beaten hollow until their brilliant songwriter-guitarist went off the rails on LSD. Re-locating to California, the Mac noodled around inconsequentially for several years until drummer Mick Fleetwood heard the album Buckingham-Nicks by aspiring songwriters Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks.

Fleetwood invited them to join the band and the first album with this new line-up took off like a rocket. On 15 February 1976, they began recording the follow-up, Rumours, at the Record Plant, Sausalito, California, USA.

“The Record Plant was this amazing hippy place,” recalls Stevie Nicks. “We like to say we were all hippies but, in the beginning, we really weren’t. But we went up to this incredible studio, which was all decorated with Indian saris and beautiful colours, there were little hippy girls everywhere making cookies … it was such a beautiful thing. You walked in and you were like, ‘Aaaaah! I love this place.”

Regrettably, however, the Mac had brought their own snakes into this hippy garden of paradise, because the two romantic relationships in the band, Buckingham-Nicks and John and Christine McVie, were rapidly disintegrating. The first thing they had to do was work out how to continue functioning as professionals when their personal lives had become seething cauldrons of disappointment, mistrust and anger. “There was pain, there was confusion,” says Buckingham, “and it all added up to make Rumours a soap opera on vinyl.”

The band aid they used to patch over their open sores was work. “We had two alternatives,” explains Christine McVie. “Go our own ways and see the band collapse, or grit our teeth and carry on playing with each other. Normally, when couples split they don’t have to see each other again. We were forced to get over those differences.” This need to maintain the band’s stability trapped them in an environment where they were precluded from publicly, or even privately, expressing their true feelings. Almost inevitably, their unspeakable despair found its way into the songs.

Bassist John McVie was not a songwriter, so Christine’s eloquently regretful reflections on their crumbling marriage, Songbird and Oh Daddy, have no response from him. “I’d be sitting there in the studio while they were mixing Don’t Stop,” he reflects, “and I’d listen to the words, which were mostly about me, and I’d get a lump in my throat. I’d turn around and the writer’s sitting right there.”

Buckingham and Nicks, however, were both songwriters, and their compositions effectively became substitutes for conversations they should have been having.

“When we were writing and recording these songs,” says Nicks, “I don’t think we really thought about what the lyrics were saying. It was only later down the line that Lindsey did come to question the lyric of my song Dreams, and my answer was that it was my counterpart to Go Your Own Way.”

“The spark for that song,” admits Buckingham, “was that Stevie and I were crumbling. It was totally autobiographical.”

Mick Fleetwood remembers Stevie being particularly upset by the words ‘crackin’ up, shackin’ up’ being directed at her by Lindsey through his song. For her part, Nicks felt that Dreams was much more empathetic than Go Your Own Way. “In my heart,” she told him, “Dreams was open and hopeful, but in Go Your Own Way, your heart was closed.”

As well as their personal problems, they soon found that the Record Plant was a strange place in which to work. There was a sunken pit in one of the studios, known as Sly Stone’s pit, which Fleetwood remembers as being, “usually occupied by people we didn’t know, tapping razors on mirrors.”

Cris Morris, the engineer who had helped build the record Plant, points out that, “A lot of other musicians dropped by. Van Morrison hung out a lot. Rufus and Chaka Khan, Rick James…”

It wasn’t long, though, before Fleetwood Mac, who were now reaping huge financial benefits of the success of their previous album, found themselves indulging in narcotic recreational pursuits. “It was the craziest period of our lives,” says Fleetwood. “We went four or five weeks without sleep, doing a lot of drugs. I’m talking about cocaine in such quantities that, at one point I thought I was really going insane.”

Somehow, though, ground-breaking work continued to get done. In the powerfully driving Don’t Stop, for example, the voices of Buckingham and McVie were deliberately equalized and compressed to such an extent that they sounded almost identical. “We were trying to get unique sounds on every instrument,” remembers Morris. “We spent ten solid hours on a kick drum sound in Studio B. Eventually we moved into Studio A and built a special platform for the drums, which got them sounding the way we wanted.”

Although the basic tracks were completed in Sausalito, there was a further period of several months in Los Angeles, largely given over to mixing plus vocal, guitar and percussion overdubs.

“Looking back at it from 56 years old,” says Nicks, “all I can think is ‘Thank god it wasn’t worse’. Thank god we didn’t get into heroin. We were lucky that we were always able to get ourselves together to make the music. Maybe it was the music that saved all of us.”

(Source : written by Johnny Black, first appeared in the book Albums, Backbeat, 2006)

The album

The album