Fact #116953

When:

Short story:

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band start work on their classic triple-album set, Will The Circle Be Unbroken at Woodland Sound Studios, Nashville, Tennessee, USA. The album brings together several generations of country-inspired musicians by featuring The Dirt Band along side such country legends as Mother Maybelle Carter, Earl Scruggs (and his banjo too), Doc Watson, Roy Acuff, Merle Travis and Jimmy Martin.

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band start work on their classic triple-album set, Will The Circle Be Unbroken at Woodland Sound Studios, Nashville, Tennessee, USA. The album brings together several generations of country-inspired musicians by featuring The Dirt Band along side such country legends as Mother Maybelle Carter, Earl Scruggs (and his banjo too), Doc Watson, Roy Acuff, Merle Travis and Jimmy Martin. Full article:

EYEWITNESS – The Making Of Will The Circle Be Unbroken?

By Johnny Black

John McEuen (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) : It was a multi-step process of events that led up to making it possible.

The first part of that process was that our album Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy had been played for Doc Watson, Jimmie Martin and Earl Scruggs by their sons in 1970. Their sons wanted them to hear this new band. We were trying to create a kind of acoustic country rock. We'd had radio hits with Mr. Bojangles and Some Of Shelley's Blues, which had banjo and harmonica on them, country instruments.

I really believe that if Jeff Hanna hadn't brought Mr. Bojangles to us when we were finishing our previous album, Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy, we might never have made Will The Circle Be Unbroken.

It was a big hit for us, and gained us credibility with the record company. It gained us some attention. If we were just a bunch of hippies from LA, with those instruments and hits, it might not have happened.

Also, the Uncle Charlie album had a couple of bluegrass instrumentals, Randy Lynn Rag and Doc Watson really liked Clinch Mountain Backstep.

In October of 1970, Earl Scruggs came to see The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band at Vanderbilt University Gym, the first time we played in Nashville. I couldn't believe he was coming so, when he showed up, I asked him why he was there, and he said, "I wanted to meet the boy who played Randy Lynn Rag the way I intended to." ... which was me.

Jeff Hanna (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) : It really started with a chance meeting we had with Earl Scruggs in the fall of 1970 when we were playing at Van Der Bilt University in Nashville. Earl and his boys and his wife, Louise, came to the show.

Louise Scruggs : Gary and Randy were going to school at Vanderbilt and told us we should see them.

Earl Scruggs : The first time I remember seeing them, they played here in Nashville. We went to the show, and were really surprised at how much they knew about me.

Louise Scruggs : We became really good friends with John McEuen. When Will The Circle was first discussed, Earl said to John, "Why don't you record legends of Nashville like Maybelle Carter and Ray Acuff?" Earl told them about these great artists whose songs were no longer recorded. Earl said, "You guys are a young group. It would be great." They followed through.

Jeff Hanna : We were such huge fans of Earl and his boys were fans of our band, so we immediately struck up a friendship and started talking about maybe recording together.

John McEuen : Earl was going on the road the following Spring with his sons, under the name of The Earl Scruggs Revue, and they played for a week at Tulagi's club in Colorado where we all lived, and every night, I'd take them back to their hotel.

Finally, while driving them on the last night, I got up enough nerve to ask him if he'd consider recording something with us, and he said, "I'd be proud to." Jeff Hanna was in the back seat of the car and I remember seeing his eyes gettin' real big.

I called my brother, Bill, that night and told him Earl had said yes.

Jeff Hanna : At this point, Bill McEuen got the idea that maybe instead of just Earl and us recording a track for our next record, maybe we could do something where we worked with a bunch of legendary country acts. So when that idea was presented to Earl, he said that yes, he’d love to take part in something like that.

Armed with that information, once we got back to Colorado, John McEuen and I drove to see Doc Watson playing in Boulder, Colorado, USA.

John McEuen : One week later, Doc Watson was playing in the same club, Tulagi's, and I was a little bolder. I talked to his son Merle, who told me he thought it would be perfect for his daddy because the folk music business was dying out. He introduced me to Doc and I told him we were going to make an album with Earl Scruggs and we'd like him to be part of it. I put him on the phone from the dressing room with my brother, and that was pretty much set in motion right there.

Jeff Hanna : This would be early 1971. We put the idea to Doc and he was interested because Earl was interested. Earl became our hook. And Doc’s son Merle was also a fan of our band so that generational thing helped.

Doc Watson : Merle got me off in the corner and said, 'Dad, do it. It will get us audiences that have never heard us before.' He had a head on his shoulders, buddy. Let me tell you that. He said, 'Do it.' He said, 'I believe you ought to. It will help us out in the long run even if they didn't invite me.' Now that was being a man.

Jeff Hanna : So with two guys on board, it got a little easier to attract more. We came down to Nashville and had a meeting with various folks.

John McEuen : So the next day, my brother says, "I'm gonna get Merle Travis," because we'd opened for Merle Travis for ten days in 1966, when we were basically a jug-band bluegrass skiffle band. So Bill got Merle to say yes.

Jeff Hanna : We extended the invitation to Merle Travis, who had been a friend of ours for some while, and he graciously accepted.

John McEuen : Then we asked Louise Scruggs if she could help us get Maybelle Carter and Jimmy Martin. We didn't know how to reach them, but it turned out that their children knew of us through our songs being on the radio. So we were kind of a big deal to them.

After Maybelle was confirmed, right around then, with Bill, who was the producer of this album, and our manager at the time, we went to the record company to get the money to make the record. And the record company president, Mike Stuart, listened patiently for half an hour and said, 'I don't know if I'll sell ten of these, but you sound so passionate about it that I'll put up $22,000'.

It was not really a lot, but it was money and that's what counted. Nowadays it would be half of the food budget for a Madonna video shoot, ended up paying for the studio, the tape, the artwork, the hotels, the musicians, everything ... let's say we used it quite well.

Jeff Hanna : It was funny. We were just coming off of this big hit single with Mr Bojangles, and a successful album, Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy, so we had enough leverage with the record company to be able to convince them that this might be a great idea. I think they saw that we were very passionate about wanting to do this record so, even though they weren’t sure if it was going to sell ten copies, they still agreed to let us do it. They gave us a budget of just $22,000 for the whole thing – and we got almost forty tracks out of those sessions. I think they just saw it as a side project. And in a way it was – we were still touring and playing as a rock’n’roll band.

I think the record company also felt that it might be a mis-step. They wanted us to get on the radio. The whole country rock thing was just starting to explode back then. You’d had Sweetheart Of The Rodeo in, I think, 1968, then there was Poco, the Flying Burrito Brothers and us on the West Coast and The Band in the East. There was also Pure Prairie League in the Midwest, but there was just a handful of us really…

John McEuen : From the moment Earl said 'I'd be proud to' to the finishing of the album was just eight weeks. Nothing was even booked. It was until about the first of July that we started thinking about getting a studio, which we booked for six days, and then Earl came up with a bass player for us.

I tried to get Josh Graves, the dobro player with Flatt And Scruggs, who was the man who made the dobro a lead instrument, but he was playing with Lester Flatt in 1970, and Lester wouldn't let it him come and play with us. Lester said, 'You're on my payroll. You're not gonna go and pick with Earl.' Old time showbusiness got in the way.

We had Oswald Kirby who we wanted to make a known name, which is why his name is on the left side of the album, because he had been a sideman to Roy Acuff, and without Earl we wouldn't have gotten Roy Acuff.

Jeff Hanna : Earl Scruggs was very important to the whole thing. He brought in Vassar Clements to play fiddle, which was great idea, and we didn’t really know who Vassar was. He had been working with John Hartford at that point.

So we had Vassar on fiddle and Junior Huskey on upright bass. Those two played on virtually every track.

John McEuen : My brother called me about week three of all this coming together and said he'd just read an interview where Acuff said he'd make real country music with anyone, anywhere, anytime. So then the call went to Acuff.

We had a meeting with him a week before the sessions, after which the Nashville Tennessean interviewed him and asked what he had thought of us, and he said, "I don't know if they're old boys or young men or what, they so covered with hair." Which we were.

We scheduled him for the last day.

Jeff Hanna : There was just one person that we didn’t get, and that was Bill Monroe, which is my only regret about the whole project. We’d have loved to have had Bill on there. His reasoning was that he didn’t think his fans would understand. I think he might have a different idea of what we were planning to do, maybe he thought we were going to electrify the music, because we were a bunch of long-haired scruffy hippies from California. At that time there was big cultural divide, and I think he was showing respect to his audience. I totally respected his decision, but I was still disappointed not to have him on the record. We did get to tour with him later, and had a great time.

It was a lot easier getting permission to play with people from other labels back then than it would be if we tried to do it now. In fact, a number of the people who played on that album didn’t even have current record deals. I don’t think Mother Maybelle Carter had a deal at that time. I could be wrong about that.

It certainly wasn’t as lawyer-driven in those days. It was a lot more complicated when we came to do Vol2 and Vol3.

Roy Acuff was a tough sell. He was reluctant at first but Bill McEuen, who is a genius at this sort of thing, had seen a quote where Roy said that he would play real country music – underlining the word real – with anyone, anyplace, so Bill said, “Let’s see if we can get him to put his money where his mouth is.”

Lo and behold, we had this meeting with him in Nashville and he was really confused by us, we were staring at each other across this conference room table, he’s looking at this rag-tag bunch of guys and he said later that he didn’t know if we were old men or young men because we had so much facial hair he just couldn’t see our faces properly.

We were the same though when we looked at them. I remember when Jimmy Martin first walked in, I thought he looked like the stereotypical Southern cop. It was just a generational thing, a different way of looking. They’d be in the studio with ties and pressed slacks, and we were in scruffy jeans and t-shits.

Roy Acuff : You’re supposed to know a man by the character of his face but if you have got your face all covered up with something, well … I’ll just tell you, they are very nice young boys … to be honest, I couldn’t tell whether they were young boys or old men, but they were very interesting and they certainly knew what they were doing.

Jeff Hanna : So, anyway, we left the meeting with Roy thinking, well, this doesn’t look too promising. He was pretty much questioning the whole thing. Then, a couple of days later, we started with first sessions with Merle Travis,

John McEuen : Once we started recording there was a 16-track machine running but when Merle Travis finished I Am A Pilgrim, there was no reason to play the multi-track. Bill was also recording two track in the hope of getting a much more pristine-sounding record which could go directly from the two track to a master. So we turned off the 16-track.

Now Bill, in his wisdom, kept another tape recorder running at seven and a half ips, throughout the whole session, so all the conversations were recorded, and they were later edited into the finished album. About one third of the people who love this album, say those are their favourite parts of the record.

Right from the first song, the banjo messes up a lick and a voice says, "Huh, Earl never did do that." Now that's not the way a record is supposed to start.

Jeff Hanna : At the end of that first day, unbeknownst to us, Roy walked into the studio…

Jimmie Fadden (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) : He just wanted to spend one day in the studio ‘cause he just doesn’t record any more. He’s pretty much retired and he’s got a country music museum and he spends most of his time on that. He didn’t want to play on the tune Will The Circle Be Unbroken ‘cause it was another day.

Roy Acuff : I did it because Wesley Rose of Acuff-Rose (music publishers) asked me to do it, because he said he thought it might sort of increase the respect between our brand of music and theirs.

Jeff Hanna : The recording process was very fluid. We would have probably two artists with us in the studio on each day, so Roy stuck his head round the door and he liked what he heard.

John McEuen : Basically, the artists picked the songs they wanted to do but also, from the start, we had in mind songs we wanted to hear each artist do. I really wanted to hear Earl do You Are My Flower, and we wanted Acuff to do Precious Jewel, but so did he.

Jimmie Martin didn't really want to do the Grand Ole Opry Song. He said, 'You know, I like that song, but a lot of those people are dead.' We had to convince him that was exactly why we needed to have it on the album.

We knew we wanted to do I Saw The Light and Will The Circle Be Unbroken with everyone. Then there was a couple with The Dirt Band, Vasser Clements and Junior Husky, and maybe Norman Blake, like Honky Tonkin' and Lost Highway, doing our viewpoint on that kind of music.

So it really was a combination of events.

Roy Acuff : They used nothing but plain country instruments, and the boy who was directing it all seemed to be doing a very good job of putting it all together.

Jeff Hanna : He actually said, ‘Well, that ain’t nothing but country. I’ll be back tomorrow, if you’re ready.’ So we were high fivin’ each other over that one.

That kind of thing doesn’t happen too often, but I remember when we were recording a track with Willie Nelson for the third volume out in LA and Tom Petty wandered in and he heard the track we were doing and he said, ‘That sounds great.’ So we asked if he’d like to come and sing on it and he said, ‘Yeah.’ Totally unexpected.

Anyway, to get back to the first Circle record, it was a big thing for us to get Roy Acuff, the King Of Country music, on there. He was pretty amazing.

Chet Flippo (journalist, Rolling Stone) : Roy Acuff, who has sold more than 25 million records, is today lending his talent and considerable prestige to an ambitious recording project, a session uniting some of the giants of traditional country music.

Close behind him strolls the session’s backbone, Earl Scruggs, banjo-picker sans-pareil, whose appearance of late at such functions as peace rallies has caused a bit of a flap in country music circles.

Jeff Hanna : Woodland Studios was a great environment to work in, a very old-timey Nashville studio, but the name doesn’t refer to it being out in the woods. It refers to the street it’s located on, over in East Nashville. It’s an extremely famous studio. A lotta hits were cut there. The thing I loved about it was that it had high ceilings, there were a couple of big rooms. As a matter of fact we went back in there to record tracks for a Buddy Holly tribute album that MCA did a couple of years back. We cut our track, Maybe Baby, in there. Gillian Welsh and her partner Dave ended up buying it.

John McEuen : We recorded for six days and on the seventh we played it all back.

We didn't even play all day, because most of the songs were captured on the first or second take. For example, we had Merle Travis scheduled from noon til five, set up the microphones, recorded a bit of guitar to see how it sounded, said, "OK, let's do it" and three minutes later that song was done.

So then someone said, 'Do Cannonball Rag' and two and half minutes later it was done. Roll On Buddy took about ten minutes. Merle was done in less than an hour.

When Earl did You Are My Flower, he ran through it a couple of times, but the actual recording was just one take. We only ever recorded a few hours a day.

Jeff Hannah : We actually found ourselves being a lot more polite, a lot less raucous than we normally were in the studio out of respect for these people and I think it was good for us. I mean, you have to mind your manners when you have someone like Mother Maybelle Carter in the room, the great matriarch of country music, and what a sweetheart, what an angel she was to work with. I still feel blessed that I got to play with her.

Our previous album, Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy, had been done in more of a standard way, although our band did have a tendency to try to record as much of a track live as we possibly could. We go back in and fool around with overdubbing backing vocals or adding a guitar or a banjo solo, but we liked to have as much live as possible.

So we were pretty spontaneous, but Will The Circle Be Unbroken was much more spontaneous than that. To get the cleanest, most pristine audio quality on the record, you couldn’t beat doing it live, because if you started combining and mixing tracks you could start losing a generation of tape, and there started to be hiss and noise on the masters. So by recording direct to two track, the masters were very clean.

We had a couple of great engineers. They did a great job and they were very patient. The vinyl version sounded great, and the only thing that sounded better was the 30th Anniversary re-mastered version. There was an earlier CD that was bit muddy because it didn’t come from the original tapes.

One good thing for us was that the record company wasn’t snooping around when we were making that album. They didn’t come anywhere near the studio. They stayed out there in LA and just left us to get on with it.

At this point, though, what none of us realised was that we were going to come out with three albums worth of material. We only recorded for about a week, so we kinda hauled butt, and it was all done live to quarter inch two-track, with all the mixing done on the fly as we were recording it. It was a fantastic work rate, but we were playing with legends – there wasn’t anybody in that studio, except for us some of the time, that didn’t know exactly what they were doing. They were all so good. There’s a bit on the record where Roy Acuff talks about getting the song right on the first take, and he really meant that.

We were just so happy to be in there playing with these guys, even just to hang out with these people… there was a kind of grand vision of getting this music out to a younger audience but, to be honest the real motive was kinda selfish – we just wanted to play with these people.

John McEuen : Despite being from different generations, there were no political or cultural divisions in the studio. I always like to remind my countrymen that our country was in the midst of the worst cultural turmoil we'd seen - churches had been burned, marchers had recently been shot and killed, Martin Luther King was still kinda warm, the Vietnam War was raging and dividing people, and yet Mr. Acuff, a staunch republican, came to the studio on that Friday, listened to what we'd been recording, and said, 'What kind of music do you boys call that?'

Bill started to say, 'Well, it's kind of Appalachian, bluegrass, mountain...'

Roy says, 'Aw, hell, that's nothin' but country music! Let's make some more.' And everybody cheered and we got on with it. Music is played on both sides of the battle lines.

Jeff Hanna : Our whole country was divided at that time because of our involvement in the Vietnam War, but frankly that wasn’t part of our agenda in making the album. I’m sure that if we had gotten into political discussions those sessions might have broken down quickly and we’d never have got the album finished. On both sides we were all on our best behaviour and it was all about the music.

One of the things that attracted people to the Circle record was that it was kind of a reminder of simpler times. It was mostly traditional songs, some Carter Family stuff, Hank Williams songs, Roy Acuff material…

You know, the guy in our band that deserves a lot of credit is John McEuen, Bill’s younger brother and our banjo player. He and Les Thompson, our mandolin player, they were so steeped in bluegrass. Jimmy Ibbotson, myself and Jimmy Fadden all loved bluegrass, but Les and John had played a lot more of it and were a lot more familiar with the music.

I think the real genius guys in the whole thing were Bill McEuen and Earl Scruggs. It was Bill who had the great vision and it was Earl who then made it possible. He was so open-minded. He could have just shut it right down from the very start. ‘Yeah, you guys are crazy, go back to California.’

John McEuen : Some really fun things happened. Lonesome Fiddle Blues was a complicated note song, and I needed to learn the notes from Vassar, so I could play it on my banjo, and said to my brother, 'How long before you think we'll be recording Lonesome Fiddle Blues?' He goes, 'Probably about three hours.'

So Vassar and I went out in the hall and he got about three quarters of the way through showing me the song, and somebody didn't arrive in time, so Bill called us into the studio before I had really learned it all. I was really on the edge but, you know, I'm glad I didn't have more time, because I like what ended up on the record, even my mistakes. I got the final phrase wrong, but it came out great. If I'd done it any other way, there would have been too many notes. It was better that it went how it went.

Another exciting thing was getting Jimmie Fadden, who we always thought was a great harp player, to learn so much from Vassar, who was encouraging him to double the melodies he was playing, or adding a couple of harmonies on top of what Jimmie was paying. It was really exciting to watch that happening in the studio.

To have Jeff singing You Are My Flower, with Earl's song Gary singing with him, that was a wonderful thing.

Jeff Hanna : We’d notched up a few years as a band ourselves, of course, but we’d started so young that I had just had my 24th birthday when we made this album. I look back and can’t believe we did it. It was so much fun, but it was a combination of fear and joy. Fear that we might screw up in the presence of these legendary musicians, and joy at just being around them.

Chet Flippo : A stately silver-haired lady enters the studio almost unnoticed while Watson runs through Tennessee Stud. She is mother Maybelle Carter and she, along with A.P. and Sara Carter, started recording as the Carter Family in 1927 in Bristol, Virginia, USA. Today she’s carrying with her the old 1929 Gibson which made her flat-picking and Carter family ‘church lick’ famous and often imitated.

Jeff Hanna : The Maybelle sessions were particularly moving because she had this kind of angelic presence. She was very soft spoken, so everybody would just quiet down and really pay attention. Musically … she had a real calming effect.

John McEuen : It was how I imagine it might be to be in the presence of The Queen. You didn't expect her to be asking your permission to sing certain songs. Maybelle would say, "I'd like to do Wildwood Flower in the key of F if you-all don't mind." I came close to saying, 'Do you realise that you're Maybelle Carter and we'll sing any song you tell us to in any key you can imagine.' She was asking our permission to sing a song that she wrote that every guitar player knew. I know for a fact, because his daughter told me, that Duane Allman showed his wife how to play Wildwood Flower.

I met Duane in the transit lounge of Atlanta airport once in the 70s and he asked me to get out my banjo and pick a tune for him. I said, 'But we're in an airport,' and he said, 'If there's anybody here in Georgia who objects to hearing a banjo, I'll deal with them.'

*** I remember that while Maybelle was out in the studio getting ready to do You Are My Flower, I picked up the phone on a call from the Columbia Records attorney telling us they had granted us permission to do one song with Maybelle Carter. Well, we'd already recorded four, so I thanked him profusely and hung up. Bill said, 'Who was that?' I said, 'No-one.' So Columbia didn't get it. The headline in the Nashville Tennessean in the week of the sessions was 'Why is the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band recording with a bunch of old dinosaurs?'

Chet Flippo : ‘There’s a dark and a troubled side of life, there’s a bright and a sunny side too,’ she sings in her sad, almost dragging tones, with Merle Travis, Gary Scruggs, Jeff Hanna, Jim Ibbotson and Les Thompson singing harmony, and the surrealistic quality of this entire production becomes more and more overwhelming.

Jeff Hanna : And the Doc Watson stuff was incredible. We just couldn’t believe we were playing with him. When we were just like little folk puppies in our teens, we used to slow down his records to try and learn how he played the things he did.

I love Tennessee Stud by Doc Watson and Keep On The Sunnyside by Maybelle. Dark As The Dungeon by Merle Travis. Grand Ole Opry Song by Jimmy Martin. Jimmy taught us a lot of little secrets about singing bluegrass. We had the harmony right, but not the phrasing.

Jimmie Fadden : He’d tell us how he wanted it.

Jeff Hanna : He’d tell us exactly how to pronounce a word – real clipped and high – like it was a foreign language.

Jimmie Fadden : The way Jimmy does it, he sings very up-tempo and in a high register and his pronunciation of words is different than say Del reeves or somebody like that.

Jeff Hanna : Believe it or not, Will The Circle Be Unbroken wouldn’t be the one I’d save. It had to be on there, and we sing it every time we play.

Jimmie Fadden : After Roy had recorded his tunes with us, he showed up, y’know (to record Will The Circle Be Unbroken). That was a sign that he liked it. He showed up and did the Circle thing. We were all getting’ ready, settin’ up the mikes and he just strolled in. It was nice.

John McEuen : Bill and I knew that getting Acuff to record with Earl Scruggs, or Doc to record with Merle Travis, who he hadn't met before but always wanted to, we knew it was important tous and to other people who were pickers. Once we got themall in the studio onthe first day, we realised that an immense thing was now underway and it was now unstoppable. But by the middle of that day we realised that everybody knew Junior, the bass player, and everybody had either played with Vassar or knew about him, and they were also big fans of each other. Maybelle Carter said, 'Oh, Roy, I've always wanted to record with you. I'm so glad we've been given this chance.' Doc was delighted to be pickin' with Earl.

We felt like a bunch of flies on the wall some of the time.

Jimmie Fadden : Bill McEuen was amazing, incredibly important to the whole project. First and foremost, he produced the record, and we were all thrilled with what we’d achieved when we got to the end of recording, and then Bill McEuen, impatient as we were, he went back and did all the sequencing. So the tracks aren’t on the album in chronological order, because he wanted to group together certain tracks and so on.

Also he had been running a seven and a half inch tape through the entire sessions, which was where he had all the talking that ended up on the album. But he had to go through and edit that too. It makes the album very cool. Of course Bill had been responsible for all that sort of thing on the Uncle Charlie album. That was the genesis of that sort of idea.

Bill also took the photographs of all the musicians during the sessions and co-designed that lovely triple-fold-out album cover with Dean Torrance of Jan And Dean. Bill and Dean had started doing our album covers with Uncle Charlie, and they did Symphonium Drean, All The Good Times, great covers.

So they went off and came up with this beautiful tri-fold album cover with all the photographs in it, just a beautiful thing to behold, but it was expensive to produce so the record company kind of choked on that, because that had to be added on to the existing budget. They tried to recoup it by charging more for the package, about $13 or $14. Most records were about $5, but it was a triple album package.

But I was really glad that Bill took the time to do what he did with it in post-production because, even though we were impatient to see it come out, we did want it to come out in the right way. It took seven months, much longer than the original recording sessions.

Of course, when it came out, they couldn’t keep the stores supplied. They couldn’t manufacture them fast enough. They were caught off guard because they really didn’t imagine that there was going to be a big demand for this album.

John McEuen : It started off very slowly but the word of mouth was incredible.

The record company was very unhappy because the cover alone was costing them a dollar and a half each to make. They were choking on it. My brother was adamant about using very expensive, thick chrome-coat board, four colour separations on six fold outs. Wait a minute! Where's the proff that this is gonna work? And it was a tedious process. Manufacturing normally consisted of pressing a record, putting it in a sleeve and shrink-wrapping it. For Will The Circle Be Unbroken, they were pressing three records, putting them in three printed sleeves that had to be carefully put together in the right order, and then putting another sleeve - a double-gatefold album where every page has four colour separations. They could only make 25,000 units at a time, and it took two weeks.

But the press reaction was so good that that the first 25,000 sold out in a day. It took another three weeks to get the next run out there, so when Billboard called to see how the album was doing, the company had to tell them, 'Well, we haven't sold one.' Then the next 25,000 sold out instantly and they started making another 25,000. After that happened about ten times and they'd sold a quarter of a million records, they decided to increase every shipment up to 50,000.

It became a gold record a year and a half after it was released, and I Saw The Light by Roy Acuff went onto the country charts. It has sold over a million units, and is still showing up on the Amazon charts.

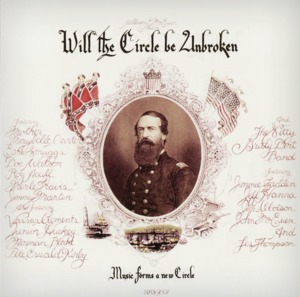

Jimmie Fadden : The guy on the cover, by the way, is a picture that Bill found in some archival magazine. I think he was a Union general, but I couldn’t tell you his name. I imagine Bill would be able to tell you.

(According to blogger Burt de Llama, “It is General Horace Porter. Born April 15, 1837 in Huntington, PA, the son of David Rittenhouse Porter (1788-1867), a two time governor of the State of Pennsylvania.” For more details click here.)

Jeff Hanna : We were very pleased, in the long run, that the album achieved a great deal, because some of these people were being largely overlooked. Vassar Clements and Jimmy Martin came out of it with re-invigourated careers.

Jimmy Martin : I got a gold album on that. We did six of my songs on the first one, and it sold four million. Then, when they called me up to do Circle 2, they wanted me to do 'Sittin' On Top Of The World', and I said, jokin'-like to 'em, 'Why you only want me to do one on the second one when you wanted me to do six on the first one and it sold four million?' Bill McEuen said, 'Hell, you stole the first one - you ain't stealin' this one!' It's just a joke, but I thought I should tell it.

Jeff Hanna : Another thing that came out of the Circle album was enduring friendships. We toured a lot with the Earl Scruggs Revue, and later on Vassar came and played fiddle with us on international tours, and we played with Jimmy Martin a lot over the years. And Roy Acuff … I was about to call him Mr Acuff…

John McEuen : You know, we didn't understand the significance of what we were doing. We certainly never imagined it would go into the Library Of Congress as one of the most important records ever made. We didn't realise it would go on selling for forty years.

When I re-mastered the album in 2002 for the 30th Anniversary, I was able to add two more cuts on the CD, and then there were two other cuts of conversations

The tough part about all this is that we're the only ones left alive. Right now I'm eighteen years older than Earl Scruggs was when we did the album, and he was considered the old guard.

Elvis Costello : The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band triple album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken, introduced me to Merle Travis, Roy Acuff, Earl Scruggs and Doc Watson. That was a revolutionary record, these longhair musicians playing with the likes of Vassar Clements. Mother Maybelle Carter was also on that album and that was the start of me listening to the Carter Family.

Tweet this Fact

By Johnny Black

John McEuen (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) : It was a multi-step process of events that led up to making it possible.

The first part of that process was that our album Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy had been played for Doc Watson, Jimmie Martin and Earl Scruggs by their sons in 1970. Their sons wanted them to hear this new band. We were trying to create a kind of acoustic country rock. We'd had radio hits with Mr. Bojangles and Some Of Shelley's Blues, which had banjo and harmonica on them, country instruments.

I really believe that if Jeff Hanna hadn't brought Mr. Bojangles to us when we were finishing our previous album, Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy, we might never have made Will The Circle Be Unbroken.

It was a big hit for us, and gained us credibility with the record company. It gained us some attention. If we were just a bunch of hippies from LA, with those instruments and hits, it might not have happened.

Also, the Uncle Charlie album had a couple of bluegrass instrumentals, Randy Lynn Rag and Doc Watson really liked Clinch Mountain Backstep.

In October of 1970, Earl Scruggs came to see The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band at Vanderbilt University Gym, the first time we played in Nashville. I couldn't believe he was coming so, when he showed up, I asked him why he was there, and he said, "I wanted to meet the boy who played Randy Lynn Rag the way I intended to." ... which was me.

Jeff Hanna (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) : It really started with a chance meeting we had with Earl Scruggs in the fall of 1970 when we were playing at Van Der Bilt University in Nashville. Earl and his boys and his wife, Louise, came to the show.

Louise Scruggs : Gary and Randy were going to school at Vanderbilt and told us we should see them.

Earl Scruggs : The first time I remember seeing them, they played here in Nashville. We went to the show, and were really surprised at how much they knew about me.

Louise Scruggs : We became really good friends with John McEuen. When Will The Circle was first discussed, Earl said to John, "Why don't you record legends of Nashville like Maybelle Carter and Ray Acuff?" Earl told them about these great artists whose songs were no longer recorded. Earl said, "You guys are a young group. It would be great." They followed through.

Jeff Hanna : We were such huge fans of Earl and his boys were fans of our band, so we immediately struck up a friendship and started talking about maybe recording together.

John McEuen : Earl was going on the road the following Spring with his sons, under the name of The Earl Scruggs Revue, and they played for a week at Tulagi's club in Colorado where we all lived, and every night, I'd take them back to their hotel.

Finally, while driving them on the last night, I got up enough nerve to ask him if he'd consider recording something with us, and he said, "I'd be proud to." Jeff Hanna was in the back seat of the car and I remember seeing his eyes gettin' real big.

I called my brother, Bill, that night and told him Earl had said yes.

Jeff Hanna : At this point, Bill McEuen got the idea that maybe instead of just Earl and us recording a track for our next record, maybe we could do something where we worked with a bunch of legendary country acts. So when that idea was presented to Earl, he said that yes, he’d love to take part in something like that.

Armed with that information, once we got back to Colorado, John McEuen and I drove to see Doc Watson playing in Boulder, Colorado, USA.

John McEuen : One week later, Doc Watson was playing in the same club, Tulagi's, and I was a little bolder. I talked to his son Merle, who told me he thought it would be perfect for his daddy because the folk music business was dying out. He introduced me to Doc and I told him we were going to make an album with Earl Scruggs and we'd like him to be part of it. I put him on the phone from the dressing room with my brother, and that was pretty much set in motion right there.

Jeff Hanna : This would be early 1971. We put the idea to Doc and he was interested because Earl was interested. Earl became our hook. And Doc’s son Merle was also a fan of our band so that generational thing helped.

Doc Watson : Merle got me off in the corner and said, 'Dad, do it. It will get us audiences that have never heard us before.' He had a head on his shoulders, buddy. Let me tell you that. He said, 'Do it.' He said, 'I believe you ought to. It will help us out in the long run even if they didn't invite me.' Now that was being a man.

Jeff Hanna : So with two guys on board, it got a little easier to attract more. We came down to Nashville and had a meeting with various folks.

John McEuen : So the next day, my brother says, "I'm gonna get Merle Travis," because we'd opened for Merle Travis for ten days in 1966, when we were basically a jug-band bluegrass skiffle band. So Bill got Merle to say yes.

Jeff Hanna : We extended the invitation to Merle Travis, who had been a friend of ours for some while, and he graciously accepted.

John McEuen : Then we asked Louise Scruggs if she could help us get Maybelle Carter and Jimmy Martin. We didn't know how to reach them, but it turned out that their children knew of us through our songs being on the radio. So we were kind of a big deal to them.

After Maybelle was confirmed, right around then, with Bill, who was the producer of this album, and our manager at the time, we went to the record company to get the money to make the record. And the record company president, Mike Stuart, listened patiently for half an hour and said, 'I don't know if I'll sell ten of these, but you sound so passionate about it that I'll put up $22,000'.

It was not really a lot, but it was money and that's what counted. Nowadays it would be half of the food budget for a Madonna video shoot, ended up paying for the studio, the tape, the artwork, the hotels, the musicians, everything ... let's say we used it quite well.

Jeff Hanna : It was funny. We were just coming off of this big hit single with Mr Bojangles, and a successful album, Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy, so we had enough leverage with the record company to be able to convince them that this might be a great idea. I think they saw that we were very passionate about wanting to do this record so, even though they weren’t sure if it was going to sell ten copies, they still agreed to let us do it. They gave us a budget of just $22,000 for the whole thing – and we got almost forty tracks out of those sessions. I think they just saw it as a side project. And in a way it was – we were still touring and playing as a rock’n’roll band.

I think the record company also felt that it might be a mis-step. They wanted us to get on the radio. The whole country rock thing was just starting to explode back then. You’d had Sweetheart Of The Rodeo in, I think, 1968, then there was Poco, the Flying Burrito Brothers and us on the West Coast and The Band in the East. There was also Pure Prairie League in the Midwest, but there was just a handful of us really…

John McEuen : From the moment Earl said 'I'd be proud to' to the finishing of the album was just eight weeks. Nothing was even booked. It was until about the first of July that we started thinking about getting a studio, which we booked for six days, and then Earl came up with a bass player for us.

I tried to get Josh Graves, the dobro player with Flatt And Scruggs, who was the man who made the dobro a lead instrument, but he was playing with Lester Flatt in 1970, and Lester wouldn't let it him come and play with us. Lester said, 'You're on my payroll. You're not gonna go and pick with Earl.' Old time showbusiness got in the way.

We had Oswald Kirby who we wanted to make a known name, which is why his name is on the left side of the album, because he had been a sideman to Roy Acuff, and without Earl we wouldn't have gotten Roy Acuff.

Jeff Hanna : Earl Scruggs was very important to the whole thing. He brought in Vassar Clements to play fiddle, which was great idea, and we didn’t really know who Vassar was. He had been working with John Hartford at that point.

So we had Vassar on fiddle and Junior Huskey on upright bass. Those two played on virtually every track.

John McEuen : My brother called me about week three of all this coming together and said he'd just read an interview where Acuff said he'd make real country music with anyone, anywhere, anytime. So then the call went to Acuff.

We had a meeting with him a week before the sessions, after which the Nashville Tennessean interviewed him and asked what he had thought of us, and he said, "I don't know if they're old boys or young men or what, they so covered with hair." Which we were.

We scheduled him for the last day.

Jeff Hanna : There was just one person that we didn’t get, and that was Bill Monroe, which is my only regret about the whole project. We’d have loved to have had Bill on there. His reasoning was that he didn’t think his fans would understand. I think he might have a different idea of what we were planning to do, maybe he thought we were going to electrify the music, because we were a bunch of long-haired scruffy hippies from California. At that time there was big cultural divide, and I think he was showing respect to his audience. I totally respected his decision, but I was still disappointed not to have him on the record. We did get to tour with him later, and had a great time.

It was a lot easier getting permission to play with people from other labels back then than it would be if we tried to do it now. In fact, a number of the people who played on that album didn’t even have current record deals. I don’t think Mother Maybelle Carter had a deal at that time. I could be wrong about that.

It certainly wasn’t as lawyer-driven in those days. It was a lot more complicated when we came to do Vol2 and Vol3.

Roy Acuff was a tough sell. He was reluctant at first but Bill McEuen, who is a genius at this sort of thing, had seen a quote where Roy said that he would play real country music – underlining the word real – with anyone, anyplace, so Bill said, “Let’s see if we can get him to put his money where his mouth is.”

Lo and behold, we had this meeting with him in Nashville and he was really confused by us, we were staring at each other across this conference room table, he’s looking at this rag-tag bunch of guys and he said later that he didn’t know if we were old men or young men because we had so much facial hair he just couldn’t see our faces properly.

We were the same though when we looked at them. I remember when Jimmy Martin first walked in, I thought he looked like the stereotypical Southern cop. It was just a generational thing, a different way of looking. They’d be in the studio with ties and pressed slacks, and we were in scruffy jeans and t-shits.

Roy Acuff : You’re supposed to know a man by the character of his face but if you have got your face all covered up with something, well … I’ll just tell you, they are very nice young boys … to be honest, I couldn’t tell whether they were young boys or old men, but they were very interesting and they certainly knew what they were doing.

Jeff Hanna : So, anyway, we left the meeting with Roy thinking, well, this doesn’t look too promising. He was pretty much questioning the whole thing. Then, a couple of days later, we started with first sessions with Merle Travis,

John McEuen : Once we started recording there was a 16-track machine running but when Merle Travis finished I Am A Pilgrim, there was no reason to play the multi-track. Bill was also recording two track in the hope of getting a much more pristine-sounding record which could go directly from the two track to a master. So we turned off the 16-track.

Now Bill, in his wisdom, kept another tape recorder running at seven and a half ips, throughout the whole session, so all the conversations were recorded, and they were later edited into the finished album. About one third of the people who love this album, say those are their favourite parts of the record.

Right from the first song, the banjo messes up a lick and a voice says, "Huh, Earl never did do that." Now that's not the way a record is supposed to start.

Jeff Hanna : At the end of that first day, unbeknownst to us, Roy walked into the studio…

Jimmie Fadden (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) : He just wanted to spend one day in the studio ‘cause he just doesn’t record any more. He’s pretty much retired and he’s got a country music museum and he spends most of his time on that. He didn’t want to play on the tune Will The Circle Be Unbroken ‘cause it was another day.

Roy Acuff : I did it because Wesley Rose of Acuff-Rose (music publishers) asked me to do it, because he said he thought it might sort of increase the respect between our brand of music and theirs.

Jeff Hanna : The recording process was very fluid. We would have probably two artists with us in the studio on each day, so Roy stuck his head round the door and he liked what he heard.

John McEuen : Basically, the artists picked the songs they wanted to do but also, from the start, we had in mind songs we wanted to hear each artist do. I really wanted to hear Earl do You Are My Flower, and we wanted Acuff to do Precious Jewel, but so did he.

Jimmie Martin didn't really want to do the Grand Ole Opry Song. He said, 'You know, I like that song, but a lot of those people are dead.' We had to convince him that was exactly why we needed to have it on the album.

We knew we wanted to do I Saw The Light and Will The Circle Be Unbroken with everyone. Then there was a couple with The Dirt Band, Vasser Clements and Junior Husky, and maybe Norman Blake, like Honky Tonkin' and Lost Highway, doing our viewpoint on that kind of music.

So it really was a combination of events.

Roy Acuff : They used nothing but plain country instruments, and the boy who was directing it all seemed to be doing a very good job of putting it all together.

Jeff Hanna : He actually said, ‘Well, that ain’t nothing but country. I’ll be back tomorrow, if you’re ready.’ So we were high fivin’ each other over that one.

That kind of thing doesn’t happen too often, but I remember when we were recording a track with Willie Nelson for the third volume out in LA and Tom Petty wandered in and he heard the track we were doing and he said, ‘That sounds great.’ So we asked if he’d like to come and sing on it and he said, ‘Yeah.’ Totally unexpected.

Anyway, to get back to the first Circle record, it was a big thing for us to get Roy Acuff, the King Of Country music, on there. He was pretty amazing.

Chet Flippo (journalist, Rolling Stone) : Roy Acuff, who has sold more than 25 million records, is today lending his talent and considerable prestige to an ambitious recording project, a session uniting some of the giants of traditional country music.

Close behind him strolls the session’s backbone, Earl Scruggs, banjo-picker sans-pareil, whose appearance of late at such functions as peace rallies has caused a bit of a flap in country music circles.

Jeff Hanna : Woodland Studios was a great environment to work in, a very old-timey Nashville studio, but the name doesn’t refer to it being out in the woods. It refers to the street it’s located on, over in East Nashville. It’s an extremely famous studio. A lotta hits were cut there. The thing I loved about it was that it had high ceilings, there were a couple of big rooms. As a matter of fact we went back in there to record tracks for a Buddy Holly tribute album that MCA did a couple of years back. We cut our track, Maybe Baby, in there. Gillian Welsh and her partner Dave ended up buying it.

John McEuen : We recorded for six days and on the seventh we played it all back.

We didn't even play all day, because most of the songs were captured on the first or second take. For example, we had Merle Travis scheduled from noon til five, set up the microphones, recorded a bit of guitar to see how it sounded, said, "OK, let's do it" and three minutes later that song was done.

So then someone said, 'Do Cannonball Rag' and two and half minutes later it was done. Roll On Buddy took about ten minutes. Merle was done in less than an hour.

When Earl did You Are My Flower, he ran through it a couple of times, but the actual recording was just one take. We only ever recorded a few hours a day.

Jeff Hannah : We actually found ourselves being a lot more polite, a lot less raucous than we normally were in the studio out of respect for these people and I think it was good for us. I mean, you have to mind your manners when you have someone like Mother Maybelle Carter in the room, the great matriarch of country music, and what a sweetheart, what an angel she was to work with. I still feel blessed that I got to play with her.

Our previous album, Uncle Charlie And His Dog Teddy, had been done in more of a standard way, although our band did have a tendency to try to record as much of a track live as we possibly could. We go back in and fool around with overdubbing backing vocals or adding a guitar or a banjo solo, but we liked to have as much live as possible.

So we were pretty spontaneous, but Will The Circle Be Unbroken was much more spontaneous than that. To get the cleanest, most pristine audio quality on the record, you couldn’t beat doing it live, because if you started combining and mixing tracks you could start losing a generation of tape, and there started to be hiss and noise on the masters. So by recording direct to two track, the masters were very clean.

We had a couple of great engineers. They did a great job and they were very patient. The vinyl version sounded great, and the only thing that sounded better was the 30th Anniversary re-mastered version. There was an earlier CD that was bit muddy because it didn’t come from the original tapes.

One good thing for us was that the record company wasn’t snooping around when we were making that album. They didn’t come anywhere near the studio. They stayed out there in LA and just left us to get on with it.

At this point, though, what none of us realised was that we were going to come out with three albums worth of material. We only recorded for about a week, so we kinda hauled butt, and it was all done live to quarter inch two-track, with all the mixing done on the fly as we were recording it. It was a fantastic work rate, but we were playing with legends – there wasn’t anybody in that studio, except for us some of the time, that didn’t know exactly what they were doing. They were all so good. There’s a bit on the record where Roy Acuff talks about getting the song right on the first take, and he really meant that.

We were just so happy to be in there playing with these guys, even just to hang out with these people… there was a kind of grand vision of getting this music out to a younger audience but, to be honest the real motive was kinda selfish – we just wanted to play with these people.

John McEuen : Despite being from different generations, there were no political or cultural divisions in the studio. I always like to remind my countrymen that our country was in the midst of the worst cultural turmoil we'd seen - churches had been burned, marchers had recently been shot and killed, Martin Luther King was still kinda warm, the Vietnam War was raging and dividing people, and yet Mr. Acuff, a staunch republican, came to the studio on that Friday, listened to what we'd been recording, and said, 'What kind of music do you boys call that?'

Bill started to say, 'Well, it's kind of Appalachian, bluegrass, mountain...'

Roy says, 'Aw, hell, that's nothin' but country music! Let's make some more.' And everybody cheered and we got on with it. Music is played on both sides of the battle lines.

Jeff Hanna : Our whole country was divided at that time because of our involvement in the Vietnam War, but frankly that wasn’t part of our agenda in making the album. I’m sure that if we had gotten into political discussions those sessions might have broken down quickly and we’d never have got the album finished. On both sides we were all on our best behaviour and it was all about the music.

One of the things that attracted people to the Circle record was that it was kind of a reminder of simpler times. It was mostly traditional songs, some Carter Family stuff, Hank Williams songs, Roy Acuff material…

You know, the guy in our band that deserves a lot of credit is John McEuen, Bill’s younger brother and our banjo player. He and Les Thompson, our mandolin player, they were so steeped in bluegrass. Jimmy Ibbotson, myself and Jimmy Fadden all loved bluegrass, but Les and John had played a lot more of it and were a lot more familiar with the music.

I think the real genius guys in the whole thing were Bill McEuen and Earl Scruggs. It was Bill who had the great vision and it was Earl who then made it possible. He was so open-minded. He could have just shut it right down from the very start. ‘Yeah, you guys are crazy, go back to California.’

John McEuen : Some really fun things happened. Lonesome Fiddle Blues was a complicated note song, and I needed to learn the notes from Vassar, so I could play it on my banjo, and said to my brother, 'How long before you think we'll be recording Lonesome Fiddle Blues?' He goes, 'Probably about three hours.'

So Vassar and I went out in the hall and he got about three quarters of the way through showing me the song, and somebody didn't arrive in time, so Bill called us into the studio before I had really learned it all. I was really on the edge but, you know, I'm glad I didn't have more time, because I like what ended up on the record, even my mistakes. I got the final phrase wrong, but it came out great. If I'd done it any other way, there would have been too many notes. It was better that it went how it went.

Another exciting thing was getting Jimmie Fadden, who we always thought was a great harp player, to learn so much from Vassar, who was encouraging him to double the melodies he was playing, or adding a couple of harmonies on top of what Jimmie was paying. It was really exciting to watch that happening in the studio.

To have Jeff singing You Are My Flower, with Earl's song Gary singing with him, that was a wonderful thing.

Jeff Hanna : We’d notched up a few years as a band ourselves, of course, but we’d started so young that I had just had my 24th birthday when we made this album. I look back and can’t believe we did it. It was so much fun, but it was a combination of fear and joy. Fear that we might screw up in the presence of these legendary musicians, and joy at just being around them.

Chet Flippo : A stately silver-haired lady enters the studio almost unnoticed while Watson runs through Tennessee Stud. She is mother Maybelle Carter and she, along with A.P. and Sara Carter, started recording as the Carter Family in 1927 in Bristol, Virginia, USA. Today she’s carrying with her the old 1929 Gibson which made her flat-picking and Carter family ‘church lick’ famous and often imitated.

Jeff Hanna : The Maybelle sessions were particularly moving because she had this kind of angelic presence. She was very soft spoken, so everybody would just quiet down and really pay attention. Musically … she had a real calming effect.

John McEuen : It was how I imagine it might be to be in the presence of The Queen. You didn't expect her to be asking your permission to sing certain songs. Maybelle would say, "I'd like to do Wildwood Flower in the key of F if you-all don't mind." I came close to saying, 'Do you realise that you're Maybelle Carter and we'll sing any song you tell us to in any key you can imagine.' She was asking our permission to sing a song that she wrote that every guitar player knew. I know for a fact, because his daughter told me, that Duane Allman showed his wife how to play Wildwood Flower.

I met Duane in the transit lounge of Atlanta airport once in the 70s and he asked me to get out my banjo and pick a tune for him. I said, 'But we're in an airport,' and he said, 'If there's anybody here in Georgia who objects to hearing a banjo, I'll deal with them.'

*** I remember that while Maybelle was out in the studio getting ready to do You Are My Flower, I picked up the phone on a call from the Columbia Records attorney telling us they had granted us permission to do one song with Maybelle Carter. Well, we'd already recorded four, so I thanked him profusely and hung up. Bill said, 'Who was that?' I said, 'No-one.' So Columbia didn't get it. The headline in the Nashville Tennessean in the week of the sessions was 'Why is the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band recording with a bunch of old dinosaurs?'

Chet Flippo : ‘There’s a dark and a troubled side of life, there’s a bright and a sunny side too,’ she sings in her sad, almost dragging tones, with Merle Travis, Gary Scruggs, Jeff Hanna, Jim Ibbotson and Les Thompson singing harmony, and the surrealistic quality of this entire production becomes more and more overwhelming.

Jeff Hanna : And the Doc Watson stuff was incredible. We just couldn’t believe we were playing with him. When we were just like little folk puppies in our teens, we used to slow down his records to try and learn how he played the things he did.

I love Tennessee Stud by Doc Watson and Keep On The Sunnyside by Maybelle. Dark As The Dungeon by Merle Travis. Grand Ole Opry Song by Jimmy Martin. Jimmy taught us a lot of little secrets about singing bluegrass. We had the harmony right, but not the phrasing.

Jimmie Fadden : He’d tell us how he wanted it.

Jeff Hanna : He’d tell us exactly how to pronounce a word – real clipped and high – like it was a foreign language.

Jimmie Fadden : The way Jimmy does it, he sings very up-tempo and in a high register and his pronunciation of words is different than say Del reeves or somebody like that.

Jeff Hanna : Believe it or not, Will The Circle Be Unbroken wouldn’t be the one I’d save. It had to be on there, and we sing it every time we play.

Jimmie Fadden : After Roy had recorded his tunes with us, he showed up, y’know (to record Will The Circle Be Unbroken). That was a sign that he liked it. He showed up and did the Circle thing. We were all getting’ ready, settin’ up the mikes and he just strolled in. It was nice.

John McEuen : Bill and I knew that getting Acuff to record with Earl Scruggs, or Doc to record with Merle Travis, who he hadn't met before but always wanted to, we knew it was important tous and to other people who were pickers. Once we got themall in the studio onthe first day, we realised that an immense thing was now underway and it was now unstoppable. But by the middle of that day we realised that everybody knew Junior, the bass player, and everybody had either played with Vassar or knew about him, and they were also big fans of each other. Maybelle Carter said, 'Oh, Roy, I've always wanted to record with you. I'm so glad we've been given this chance.' Doc was delighted to be pickin' with Earl.

We felt like a bunch of flies on the wall some of the time.

Jimmie Fadden : Bill McEuen was amazing, incredibly important to the whole project. First and foremost, he produced the record, and we were all thrilled with what we’d achieved when we got to the end of recording, and then Bill McEuen, impatient as we were, he went back and did all the sequencing. So the tracks aren’t on the album in chronological order, because he wanted to group together certain tracks and so on.

Also he had been running a seven and a half inch tape through the entire sessions, which was where he had all the talking that ended up on the album. But he had to go through and edit that too. It makes the album very cool. Of course Bill had been responsible for all that sort of thing on the Uncle Charlie album. That was the genesis of that sort of idea.

Bill also took the photographs of all the musicians during the sessions and co-designed that lovely triple-fold-out album cover with Dean Torrance of Jan And Dean. Bill and Dean had started doing our album covers with Uncle Charlie, and they did Symphonium Drean, All The Good Times, great covers.

So they went off and came up with this beautiful tri-fold album cover with all the photographs in it, just a beautiful thing to behold, but it was expensive to produce so the record company kind of choked on that, because that had to be added on to the existing budget. They tried to recoup it by charging more for the package, about $13 or $14. Most records were about $5, but it was a triple album package.

But I was really glad that Bill took the time to do what he did with it in post-production because, even though we were impatient to see it come out, we did want it to come out in the right way. It took seven months, much longer than the original recording sessions.

Of course, when it came out, they couldn’t keep the stores supplied. They couldn’t manufacture them fast enough. They were caught off guard because they really didn’t imagine that there was going to be a big demand for this album.

John McEuen : It started off very slowly but the word of mouth was incredible.

The record company was very unhappy because the cover alone was costing them a dollar and a half each to make. They were choking on it. My brother was adamant about using very expensive, thick chrome-coat board, four colour separations on six fold outs. Wait a minute! Where's the proff that this is gonna work? And it was a tedious process. Manufacturing normally consisted of pressing a record, putting it in a sleeve and shrink-wrapping it. For Will The Circle Be Unbroken, they were pressing three records, putting them in three printed sleeves that had to be carefully put together in the right order, and then putting another sleeve - a double-gatefold album where every page has four colour separations. They could only make 25,000 units at a time, and it took two weeks.

But the press reaction was so good that that the first 25,000 sold out in a day. It took another three weeks to get the next run out there, so when Billboard called to see how the album was doing, the company had to tell them, 'Well, we haven't sold one.' Then the next 25,000 sold out instantly and they started making another 25,000. After that happened about ten times and they'd sold a quarter of a million records, they decided to increase every shipment up to 50,000.

It became a gold record a year and a half after it was released, and I Saw The Light by Roy Acuff went onto the country charts. It has sold over a million units, and is still showing up on the Amazon charts.

Jimmie Fadden : The guy on the cover, by the way, is a picture that Bill found in some archival magazine. I think he was a Union general, but I couldn’t tell you his name. I imagine Bill would be able to tell you.

(According to blogger Burt de Llama, “It is General Horace Porter. Born April 15, 1837 in Huntington, PA, the son of David Rittenhouse Porter (1788-1867), a two time governor of the State of Pennsylvania.” For more details click here.)

Jeff Hanna : We were very pleased, in the long run, that the album achieved a great deal, because some of these people were being largely overlooked. Vassar Clements and Jimmy Martin came out of it with re-invigourated careers.

Jimmy Martin : I got a gold album on that. We did six of my songs on the first one, and it sold four million. Then, when they called me up to do Circle 2, they wanted me to do 'Sittin' On Top Of The World', and I said, jokin'-like to 'em, 'Why you only want me to do one on the second one when you wanted me to do six on the first one and it sold four million?' Bill McEuen said, 'Hell, you stole the first one - you ain't stealin' this one!' It's just a joke, but I thought I should tell it.

Jeff Hanna : Another thing that came out of the Circle album was enduring friendships. We toured a lot with the Earl Scruggs Revue, and later on Vassar came and played fiddle with us on international tours, and we played with Jimmy Martin a lot over the years. And Roy Acuff … I was about to call him Mr Acuff…

John McEuen : You know, we didn't understand the significance of what we were doing. We certainly never imagined it would go into the Library Of Congress as one of the most important records ever made. We didn't realise it would go on selling for forty years.

When I re-mastered the album in 2002 for the 30th Anniversary, I was able to add two more cuts on the CD, and then there were two other cuts of conversations

The tough part about all this is that we're the only ones left alive. Right now I'm eighteen years older than Earl Scruggs was when we did the album, and he was considered the old guard.

Elvis Costello : The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band triple album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken, introduced me to Merle Travis, Roy Acuff, Earl Scruggs and Doc Watson. That was a revolutionary record, these longhair musicians playing with the likes of Vassar Clements. Mother Maybelle Carter was also on that album and that was the start of me listening to the Carter Family.