Fact #113698

When:

Short story:

Full article:

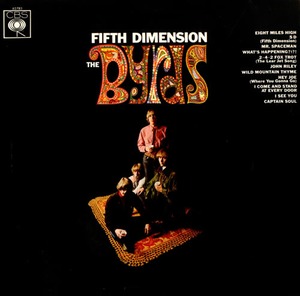

THE BYRDS – FIFTH DIMENSION

by Johnny Black

First published in Hi Fi News

From the moment they hit the airwaves in 1965 with their chiming 12-string infused version of Bob Dylan's Mr. Tambourine Man, The Byrds were arguably the most innovative mainstream band of the era. Lifelong devotees (me included) still loudly trumpet their achievements in the vanguard of every new wave of sixties music from folk-rock to country-rock, space-rock and raga-rock.

Although their third album, Fifth Dimension, was condemned as a patchy affair by several critics on release in 1966, in retrospect it clearly threw open the gates to yet another influential genre – psychedelia.

The use of mind-bending drugs was being widely advocated by radicals in the underground arts community from the early 60s. Early references to psychedelia and LSD cropped up first in tracks by two Greenwich Village avant-garde folk bands – The Holy Modal Rounders and The Fugs. By the end of 1965, several artists – The Psychedelic Rangers, Malachi, Kim Fowley and others - were applying the term psychedelic to their music.

It was Fifth Dimension, however, which presented the world with its first fully-realised psychedelic rock songs – notably Eight Miles High, 5D, What's Happening, I See You and 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song).

So when I interviewed Byrds' leader Roger McGuinn for this feature, my first priority was to establish whether or not they had deliberately set out to invent psychedelic music. "Not at all," he replied politely but firmly. "We were just trying to make a varied set of tracks that would work together as an album and, because of the various influences within the band at the time, for example our exposure to John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar, some of the tracks just came out that way. Then, because of what was going on all around, our listeners interpreted what we did as psychedelic."

The atmosphere within the group around the time of the recording sessions was not good. Gene Clark, partly because of a fear of flying, had quit the group and David Crosby was looking to increase his role within the hierarchy. "Gene refused to fly to a tv show in New York," explained McGuinn. "He just got off the plane in LA, and that was it. Crosby was also getting a little bit antsy. He was worried that he wasn’t getting enough of his own songs on the album, so there was tension building."

Before Clark's departure, however, he contributed significantly to the writing and recording of Eight Miles High, which would become the album's first single. "A friend of Crosby’s had a copy of John Coltrane’s latest album, which had that little melody line we used for the opening of the lead guitar part in Eight Miles High. We made a tape of it and listened to it over and over again on our tour bus until it saturated us. By the time we got back to LA to start recording it was kind of ingrained. I’d been practising jazz and blues scales a lot so that thing just came out."

Two versions of Eight Miles High were recorded, but the first, from December 22, 1965, was rejected by Columbia Records, largely because the band had used their manager Jim Dickson as producer. Columbia house producer Allen Stanton was brought in to oversee a new version, taped on 25 January 1966. It has gone on to be recognised as an all-time classic rock single, but David Crosby has always asserted that the original was even better, saying, "It was stronger, it had a lot more flow to it. It was the way we wanted it to be."

McGuinn now concedes that Stanton (who produced the rest of the album as well) was not a satisfactory collaborator for The Byrds, and that his contributions to the sound of the album were minimal.

The next track laid down was the whimsical Mr. Spaceman, a light-hearted country-flavoured novelty item about an alien encounter. McGuinn describes it as, "one that just sort of arrived. It's a silly song but I just started playing guitar one day and got a series of chords that I liked and hooked up a melody to it. And then I was looking out the window and kind of fantasizing about a flying saucer landing out there in the front yard. The song came out in probably about thirty minutes."

Crosby weighed in at an April 29 session with the first of what would prove to be many metaphysical ruminations, What's Happening?!?!. With its doom-laden descending bass pattern and trippy guitar lines, it's very much one the album's pioneering psychedelic triumphs. "It asks questions of what's going here and who does it all belong to," he has explained. "Each time I ask the questions, McGuinn answers them on the 12-string. He says that same thing with the instrument musically."

Another ground-breaker was 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song), recorded on May 3. Arguably a knock-off novelty, it nevertheless boldly incorporated documentary audio footage of a Lear Jet taking off and in flight, complete with radio talkback, against a minimalist Rickenbacker riff and an even more minimal one line lyric, "Go 'n ride the Lear Jet, baby". If Kraftwerk had done this a decade later, it would have been hailed as genius.

In a burst of studio activity between May 16 and May 25, the rest of the album came together quickly, including the deeply moving anti-nuclear anthem I Come And Stand At Every Door, based on a Nazim Hikmet poem set by McGuinn to the melody of the folk ballad Great Selchie Of Shule Skerry. On May 17, Crosby achieved his long-held ambition to do a speedy version of Billy Roberts' Hey Joe, a staple of the Los Angeles club scene at the time, and the powerful but inconsequential bluesy instrumental Captain Soul was taped the next day. "God knows what they had on their minds," said bassist Chris Hillman when asked about Captain Soul. "How embarrassing."

Further evidence of Crosby's increasing maturity as a songwriter came on May 19 with the jazzy changes and enigmatic lyric of I See You, after which the album's masterful opening cut, 5D (Fifth Dimension) was recorded on May 25.

Like Eight Miles High, 5D's dreamlike lyric added fuel to accusations that The Byrds were promoting drug use but McGuinn is adamant that this was not so. "I had read a book, 1-2-3-4, More, More, More, More," he reveals, "which was about the possibility of additional dimensions beyond time and space. That's what I was singing about."

The Bach-like organ part in the track was supplied by young session player Van Dyke Parks who would, of course, go on to collaborate with The Beach Boys before establishing his own acclaimed solo career.

On the same day, perhaps anxious that they had left their signature folk-rock sound too far behind, they recorded the traditional songs Wild Mountain Thyme and John Riley, both using simple but effective string arrangements by Allen Stanton.

One anomaly remains the decision to leave a much-loved Byrds artefact, Why (recorded on 24 January), off the album. Sonically, it's an ideal companion piece to Eight Miles High, and its inclusion would have made Fifth Dimension a significantly stronger whole. McGuinn says he cannot now recall why it was not chosen, but seems to suggest it was considered too similar to other tracks. "We made a conscious decision to get out of the folk-rock box into new areas," he says, "We didn’t want to be categorised in one musical genre."

Released on March 16 as the album's first single, Eight Miles High failed to achieve the chart status that could have spurred massive sales for Fifth Dimension. The widely-held perception that it was promoting the use of drugs meant that many deejays refused to play it. McGuinn stated then, and still insists today that, "Lyrically it was about the airplane ride to England for our first tour and the cultural shock we experienced when we got there. Yes, we were doing drugs, but Eight Miles High Wasn’t a commercial for it. Some people put together the word ‘high’ with our appearance and came to a rather superficial conclusion."

Fifth Dimension was released by Columbia on July 18, 1966, and influential critic Jon Landau of Crawdaddy! magazine spoke for many critics when he declared that it "cannot be considered up to the standards set by The Byrds' first two." It went on to peak at No44 on the Billboard Hot 100 but completely failed to chart in the UK

Widely misunderstood on release, Fifth Dimension has grown in stature over the decades and is now regarded as a watershed album of the 60s.

------------------------------------

PRODUCTION NOTES

by Johnny Black

By the time of Fifth Dimension, The Byrds were recording on 8-track but McGuinn chuckles when he recalls, "The 8-track recorders had been in the Columbia studio for ages but the staff were very conservative about new equipment, so the machines were stuck in a corner with a sign hanging on them indicating that they should not be used."

Perhaps the most distinctive advance in the sound of Fifth Dimension, though, was the sound of McGuinn's 12-string Rickenbacker which previously had been employed to create a folksy chiming accompaniment. On tracks like Eight Miles High, What's Happening?!?! and 5D, however, it had metamorphosed into a futuristic wail of passion.

The route to this sound began back in 1965 during the recording of Mr. Tambourine Man. In McGuinn's own words, "The 'Ric' by itself is kind of thuddy. It doesn't ring. But if you add a compressor, you get that long sustain. To be honest, I found this by accident. The engineer, Ray Gerhardt, would run compressors on everything to protect his precious equipment from loud rock and roll. He compressed the heck out of my 12-string, and it sounded so great we decided to use two tube compressors in series, and then go directly into the board. That's how I got my 'jingle-jangle' tone. It's really squashed down, but it jumps out from the radio. With compression, I found I could hold a note for three or four seconds, and sound more like a wind instrument. Later, this led me to emulate John Coltrane's saxophone on Eight Miles High. Without compression, I couldn't have sustained the riff's first note."

The album's closing track, 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song) was arguably the album's other most innovative recording for the way in which it mixed a location recording, on a portable Ampex tape recorder, of jet noises throughout the entire track, and placed it very high in the mix. Many have dismissed it as a simple gimmick but, from the start, David Crosby always championed the song describing it as "another direction we've gone into. We've mixed the sound of the jet and the sound of the people talking on the radio and the sounds of the instruments – all the sounds you would go through if you were taking off in a Lear jet."

Sound effects and found sounds had been used in popular music earlier, such as the rattling chains and creaking coffin in 1962's Monster Mash by Bobby 'Boris' Pickett And The Crypt-Kickers or the seagulls and crashing waves in 1964's Remember (Walking In The Sand) by The Shangri Las. However, by elevating the jet recording from a simple background sound effect to an integral part of the entire track, The Byrds were in tune with the most avant-garde composers of the era.

---------------------------------------

THE BYRDS QUOTES ABOUT FIFTH DIMENSION

Chris Hillman : I didn't contribute much, but Fifth Dimension, the song, is one of my all-time favorite McGuinn songs. And I've said this for years. I think Fifth Dimension's one of the better songs he's ever written and sung. I love that tune. I think that Roger and I got more as a team in Notorious Byrd Brothers, when we started to play around in the studio with stuff. Prior to that, [the most psychedelic Byrds records] that was more Roger's deal. I would play on it, but it wasn't something I was involved in, other than as the bass player. And he had that side of him, musically, that was not my style of music. It really wasn't something that I loved that much. But I was a player, and that's his piece of material, so I supported it. But I sort of dragged him into the country stuff, so it works both ways. And he performed quite well with that stuff.

(SOURCE - Interview with Richie Unterberger ca. 2000)

Chris Hillman : It was 1966. While in the Byrds, we were doing a session recording the track Eight Miles High. I thought we (all members of The Byrds) took a huge left turn musically by recording that song, which of course, has been redone on my latest album, The Other Side. It should've been a top 10 or number one single back then. However, it was labeled as a drug use song by the critics - which was untrue. It was really about flying to London in 1965 for the very first time. As a piece of music, that was radically a departure from what we were accustomed to.

(Source : interview with David Strickler 2007)

Roger McGuinn : Well, the song ('Mr.Spaceman') lends itself to that type of thinking because it is silly in the middle. Blue-green footprints that glow in the dark is a silly line and I sort of regret putting that in there, but I was trying to put out my feelings. I had just read a flying saucer book or two, or three, or four and I had just gotten into flying saucer books, testimonials -- highway patrol officer so-and-so was driving down highway such-and-such and he saw this orange light come in front of him and his car stopped and he got out and flashing red lights came on. Like all those books have the same reports in them basically. Some of them are real and some of them aren't. Incidentally, I'm glad they closed up Project Blue Book. Nobody's recorded any flying saucers lately, have they?

(Source : interview with Vincent Flanders, 1969)

Roger McGuinn : Some songs are more studied and more calculated. Others songs just pop into your head. Mr. Spaceman was one that just sort of arrived. It's a silly song but I just started playing guitar one day and got a series of chords that I liked and hooked up a melody to it. And then I was looking out the window and kind of fantasizing about a flying saucer landing out there in the front yard. The song came out in probably about 30 minutes.

(Source : Reveries 2001)

Roger McGuinn : Technically it (Eight Miles High) should have been six miles high, but six miles high didn't sound as good poetically.

(Source : interview on BBC London, 2009)

Roger McGuinn : I think (in the 5D era) maybe we got too much flack for doing too many Dylan songs.

It was basically the fact that he (Gene Clark) was kinda fried. He was burned out and the fear of airplanes was just all of it coming to a head. He also had an ambitious streak, and he wanted to go off as a solo artist. Pickner and Dickson were grooming him to be the Elvis Presley. So, there was another sort of ...a sinister plot. It didn't work out.

We decided to stay with four. We talked to the Beatles and they said that they had had five guys and they liked being four better. We said if it was good enough for them, it was good enough for us.

He (Chris Hillman) was a little shy, but he grew into it. Over the years, he's really gotten good. He's a real melodic bass player.

Those ('Wild Mountain Thyme' and 'John Riley') were my arrangements.

It's ('I Come And Stand At Every Door') a Pete Seeger influence. I got it from a Pete Seeger record. He had always been an influence and an inspiration to me, and I thought I'd put it on there. Actually, Pete asked me where I got it, too.

That's ('I See You') an early sessions, bubblegum type of song. I did like the jazzy kind of feel to it.

I'd been playing around with that jazz, Coltrane type of influence. It kinda seeped into everything I did at that point.

I have no idea why it ('Why?!') was omitted.

I think the RCA (version of 'Eight Miles High') has a little more fire, but I think we had been practicing it enough by the time we got into the CBS studio that it came out a little cleaner. It got a little more musical tightness. They both have merit.

The Gavin Report knocked it out.

It's funny, but I remember we were dealing with a female DJ in New York City. When the single came out, we played it for her and she said, "Oh. Where's the single?" I said, "That is the single." She just shook her head, like, "Yuch.

It was getting up the charts. It was up to number twelve or something. It would've gone to the Top 10. It was pretty abstract.

Gene came up with the chord changes, for the initial verses. And, Gene and I worked on the lyrics -- it was my idea to make it about the airplane ride over to England, and so we kinda worked on the lyrics. And Crosby helped with that, and then, basically, that was it. Then I did the guitar work. It was a Gene-rooted song, but Crosby and I helped.

It's ('I know My Rider') an old folk song. We all knew it from playing around in the Village in different coffee houses.

(Source : musicangle 2004)

Chris Hillman : There's things I'd never heard before. I'd forgotten we'd put an organ on the song 5D - by the way, [that's] one of the greatest songs Roger McGuinn has ever written. He'd probably never admit that. That's one of the best songs - I love that song. It just swings like a big pendulum. And the other thing, I'm throwing these at you and you can assemble them later, but Michael Clarke got so much bad press as a drummer, and he was an undisciplined drummer, but there were moments when he zapped. You know, "Eight Miles High," he was wonderful. A lot of songs, he was great on. I listened to them and I just went, "God."

David plays great rhythm.

The state of affairs with The Byrds and having been out on the road, and playing after a year or so. "8 Miles High," of course, we'd been listening to John Coltrane and we'd been on a Dick Clark rock and roll tour, and we constantly had music on our RV. We were between John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar at that point. In fact, we did 5D after that particular road trip, and we took that left turn. We didn't sit down and say, "let's do this." It just happened. "8 Miles High" was about that trip to England, and Gene once again comes up with this great imagery - exactly to the point, of when you touch down, blah blah blah, describing London and the summer. It was cloudy, we were tired, it was just a very interesting end result of that tour.

Well, he (Gene Clark) was under a lot of pressure. That was just part of it, I think. I don't think he liked flying, but that was part of it. There was a lot of pressure, and he wasn't happy and I think there was some dissension among the other principal singers at the time, and it just got to him. He had problems before that, it just ... he was a great guy. Here's this very nice kid from Kansas, but I think Hollywood, of all the cliched things, just ate him up and spit him out. I think Gene probably would have had a really good life in the Midwest. But, I don't know. He was just a tortured guy, from the getgo. It's too bad. He left, and then I tried singing.

It was nice to be out in the front and do that (singing), and it was also hard to do it for a while, but it was good. The door opened and I sort of took advantage of it. I didn't take advantage until the next record, you know, after 5D.

I wasn't really singing much, other than doubling Roger. See, what Gene did was double Roger, there wasn't really a three, distinct tenor-baritone lead, there was just two leads and David. It was interesting because the voice that came out of Roger and Gene was interesting. But, that's basically it. They didn't do the same parts; I don't know why. Because when we went in to do the box set, we did three-part on "He Was A Friend of Mine" and everything else.

Well, that's ('Hey Joe') okay. I think that David did it really good, but I don't remember. I think that I don't take it as seriously because the Lees, kind of this Byrds-clone, put it out. It was one of David's songs he always did. David probably did that when he was a folk singer when he was solo, before The Byrds. I'm sure he did. I'd guarantee it. I think David did it as a soloist and brought it in and we worked it out electrically, then Hendrix did it. Hendrix did it great. Really, really, interesting.

I don't even remember the words to "The Lear Jet Song." Let's file that under "novelty." "Captain Soul ..." God knows what they had on their minds ... how embarrassing. This album, I think there are two or three really good, interesting tunes, led by "8 Miles High" and "5d." The rest were just scattered. I don't think we knew what we were doing. I think we were just about either in a management change or something with Gene leaving.

I think the RCA (version of 'Why?!') is better -- I think it flows better. Once again, Mike was really interesting on this song. We were coming off of a road trip listening to John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar, and John Coltrane comes out through the "8 Miles High" situation. "Why" comes out through a lot of Ravi Shankar, and it's great. I love it. It's a neat song. Since we were doing "Why" in the Victor thing too, it might stand that the "8 Miles High" from RCA is better, along with that track.

That's ('I Know My Rider') an old folk song that we were just kicking around. Everybody used to sing that in the old folk days.

It's just a song ('John Riley') that Roger wanted to put on and I didn't care for it too much. He's into that kind of material to this day. He does it really well -- just a different style of stuff than I'm used to doing.

(Source : Musicangle 2004)

David Crosby : But Fifth Dimension and Younger Than Yesterday, where we really actually started to shine, I don't think they had producers did they?

Yes, he (Allen Stanton) was Columbia's idea of just having someone there to make sure we didn't [hurt] the place.

Other people were telling him (Gene Clark) he could be the next Elvis and that he was... you know, that he didn't... the standard thing...the same shit that fucking Yoko whispered in John's ear 'you don't need those guys, you're a star'. Jesus Christ, think about it. The two guys who could have had any two women on earth...... My god!!! And Gene was afraid of airplanes. We were going to a gig, we all got on the airplane he was very very nervous, he'd probably gotten himself chemically enhanced before he got on and he was sitting there and he too high or whatever it was, he panicked and got off the plane. And Roger's response was 'if you can't fly, you can't be a Byrd.'

Gene was never meant for that man. If Gene had instead gone to Nashville, he probably would have been a huge star because he was good looking- a good looking young guy. A good singer and a good writer and he had a charisma, you know? He was a great guy.

We were on tour. We were out. We were all pot smokers, so we couldn't ride on the regular bus with everybody else. We got a Winabago and drove it ourselves. And in the course of driving the Winabago one night we're driving from one town to another and Gene comes butt surfing up to the front of the thing and says 'I've got this song started' and he had part of the second half of the verse. So I came up with the chords to the 'eight miles high' part. And he came up with the other part. And he had words and we started working around with the words- all of us contributed to it. I came up with "rain gray town" and some other things and Roger came up with some other stuff. It was the first song we organically wrote together that freely that well and while we were on that tour I kept playing a tape machine- a reel to reel machine- hooked up to a Fender amplifier and we were playing John Coltrane's Africa Brass and if you listen to it you'll find on either "India" or the title track, you'll hear where the McGuinn solo came from. The opening notes are a straight cop from a Coltrane solo. It was really powerful music and it affected all of us. This wild, crazy, beautiful music.....And then they took it off the air!

Yea, there was a newsletter guy who took this big stand that that song and "Rainy Day Women" (everybody's gotta get stoned) had to go because they were breaking down our moral fiber....

Yea, that ('Why?!') came from me playing Ravi Shankar in McGuinn's ears for years. I turned everybody I could find onto that. I did that for a long time. George (Harrison) credits me with turning him onto it I think. I did that for a long time and then I did that with that women's Bulgarian folk Choir.

(Source : - Musicangle 2004)

Gene Clark : (About Eight Miles High): I had an idea for some lyrics and wrote them on a piece of paper during the conversation with Brian. Later on I found them in my jacket pocket on the tour bus. I took my guitar and started making up a melody for it. I pretty much completed the song and played it for McGuinn and Crosby, and they really liked it. There were a lot of images I got from thinking and remembering things we'd done on the English tour. Actually, I started the thing before we got to England, and finished it when we got back. We were listening to a lot of Coltrane and Shankar. I felt that the arrangement idea McGuinn came up with alone deserved co-writer credit on it. Crosby, as well, came up with some of the lyrics. I kinda felt that all three of us wrote the song.

(Source : Cosmic American Music News, 1992)

Gene Clark : I wrote all the words (to Eight Miles High) except for one line that David wrote (Rain grey town), and then Roger arranged it, basically, so I had to part something with those guys.

I decided that I wasn't going to get a single out of this deal, because I'd already written so many songs with this group that they're gonna grab up the singles for their own stuff, you know so I split it with them so I could get a single. That and they really did help me write it, too. But one of the problems we had by the release of the second album was the animosity growing amongst the group. Especially about me, because I was making a lot more money than anybody else from the royalties.

(Source : Interview with Chris Hollow, 2000)

David Crosby : We first cut the song (Eight Miles High) at RCA studios with Dave Hassinger (a producer). It was fantastic! The song just took off. But we'd done it secretly, without Columbia's approval. So they made us redo it with union nerds. The record company slapped our hands if we tried to touch the board. It was a shame. The version that got released was'nt nearly as good.

It (Why?) was all mine. That was one of the first songs I ever wrote that I really liked. It was saying something and questioning.

(Source : Crosby, Stills And Nash Biography, 1984)

Roger McGuinn : What I'm talking about is the whole universe, the Fifth Dimension, which is height, width, depth, time and something else. But there definitely are more dimensions than five. It's infinite. The Fifth Dimension is the threshold of scientific knowledge. See, there are people walking around practicing fifth dimensional ways of life and the scientists are still on two or three dimensional levels. There's a conflict there. A lot of our world is very materialistic and scientific. It overlooks the beauty of the universe. That's what the song is about. Maybe I'll tell a few people what's going on in life.The organ player on it is Van Dyke Parks. When we came into the studio I told him to think Bach. He was already thinking Bach before that anyway.

(Mr. Spaceman) began as a serious, melodramatic screenplay. I thought the song being played on the air might be a way of getting through to them (friendly aliens).

(On Eight Miles High) we were playing 12-string Rickenbacker to sound like a saxophone. We were translating jazz into a rock form.

Gene said eight miles high sounded better than six and it did sound more poetic. It was also around the time of 'Eight Days A Week' by the Beatles, so that was another hook..

The reason Crosby did lead vocal on 'Hey Joe' was because it was his song. He didn't write it but he was responsible for finding it. He'd wanted to do it for years but we would never let him. Then both Love and the Leaves had a minor hit with it and David got so angry that we had to let him do it.

Essentially, it (Captain Soul) was Mike Clarke's trip. He wanted us to do something soul-oriented, so we did that for him.

(Source : CD Liner Notes, 1996

David Crosby : It's a very strange song (What's Happening ?!?!). It asks questions It asks questions of what's going here and who does it all belong to and why is it all going on. I just ask the questions because I really don't know the answers. Actually, each time I ask the questions McGuinn answers them on the 12-string. He says that same thing with the instrument musically. You can tell it, you can feel it.

(The RCA cut of Eight Miles High) was stronger. It had a lot more flow to it. It was the way we wanted it to be.

(Source : CD Liner Notes, 1996)

David Crosby : I'm a better harmony singer than Roger. That was my gift. I could complement Gene's songs very well. But that had a lot to do with the nature of Gene's songs. Gene wrote changes that lent themselves to my kind of nonparallel, contrapuntual kind of harmony. One of the reasons the Byrds did what they did, sounded the way they sounded, was that if you have three parts, all the places to move are taken up. So you can really only move the three parts basically parallel. It takes a lot of effort to get them not to be parallel. Crosby, Stills & Nash managed that, but almost nobody else. Other than that, when you hear three voices, they're mostly moving parallel. If you have three, then one's on the top and the other one can move around between the third, the fifth, the fourth, the sixth. The other one has all the room to move, to create that tension by the relationship between it and the melody. And because just about all the Byrds' harmony was two-part, I had room to move. So my harmony could become a second melody and that creates emotional tension. It just does. For example the melody in 'Eight Miles High'. You can't do that in three-part, it's much more difficult.

It ('Eight Miles High') was my favourite moment. It was when we actually started to come into our own.

(Source : interview with John Einarson, Mr. Tambourine Man, 2005)

Gene Clark : I had an idea for some lyrics (Eight Miles High) and wrote them on a piece of paper during the conversation with Brian (Jones of the Rolling Stones). Later on I found them in my jacket pocket on the tour bus. I took my guitar and started making up a melody for it. The initial idea was discussed on the plane over the Atlantic on our trip to England, but the actual writing of it started on a tour with the Stones when we were back in the States.

(Source : interview with John Einarson, Mr.Tambourine Man, 2005)

Gene Clark : I started writing a poem that didn't have any music. And the poem had words to it like ' Eight miles high, and when you touch down, you find that it's stranger than known'. I was into it because I was writing about a trip we had just done to England and the culture shock going over there and being very famous and having to live up to that. So I just came up with a couple of chords to play the poem to Roger and David with. We had been listening to these tapes of Indian music, Ravi Shankar, and John Coltrane all this time because we enjoyed listening to that kind of music, it was good travelling music. And Roger, I remember, suggested, 'Well, why don't we take that poem and put it to this kind of jazz rhythm and do the kind of Coltrane licks in it' because it was so into our heads. So then David came in and said 'Yeah, that sounds good. Let's arrange this', and it ended up the three of us collaborating on the song and that became 'Eight Miles High', which was the influence that we got from Coltrane's 'Africa Brass' and 'India'.

I wrote all the words except for one line that David wrote ' Rain gray town, known for its sound' and then Roger arranged it, basically, so I had to part something with those guys. There were a lot of images I got from thinking and remembering things we'd done on the English tour. I decided that I wasn't going to get a single out of this deal, because I'd already written so many songs with this group that they're gonna grab up the singles for their own stuff, you know, so I slit it with them so I could get a single. That and they really did help me write it, too.

(Source : CHUM Radio Interview, Toronto, 1978)

Roger McGuinn : I think I wrote some of the words (for 'Eight Miles High') too. Gene didn't have it all done. First of all it was my idea to write it about the airplane, the 'eight miles high and when you touch down' was my idea. It wasn't a done song. We kind of said 'What'll we write about?' because Gene had the chords, the changes, the Em, G, D and C. I think I might have come up with the C down to Am thing because that was like a Bob Gibson riff I used to do. So it was a collaborative effort. In hindsight, I think Gene kind of gave himself more credit for it. He was upset at one point about a song we did later in McGuinn, Clark & Hillman and said 'I'm not going to let this happen again where you guys get credit for a song I wrote'.But it's not totally true. We really did collaborate on it. I can't give you specifically who wrote what lines but I know I was involved in the writing process as well.

We listened to it (John Coltrane's 'India') so many times over and over that when we got back to the studio in L.A. it was steeped into us and we started playing that kind of music. The guitar break was obviously a tribute to John Coltrane. That's one of my favourite guitar things I've ever done.

(Source : interview with John Einarson, Mr.Tambourine Man, 2005)

Gene Clark : It ('Eight Miles High') was about lots of things. It was about the airplane trip to England, it was about drugs, it was about all of that. A piece of poetry of that nature is not limited to having it have to be just about airplanes or having it have to be just about drugs. It was inclusive because during those days the new experimenting with all the drugs was a very vogue thing to do, so people were doing all that at that time. All that was kind of in the poetry. But it has meanings of both. It's partially about the trip and partly about drugs.

(Source : interview with Domenic Priore, 1985)

Tweet this Fact

by Johnny Black

First published in Hi Fi News

From the moment they hit the airwaves in 1965 with their chiming 12-string infused version of Bob Dylan's Mr. Tambourine Man, The Byrds were arguably the most innovative mainstream band of the era. Lifelong devotees (me included) still loudly trumpet their achievements in the vanguard of every new wave of sixties music from folk-rock to country-rock, space-rock and raga-rock.

Although their third album, Fifth Dimension, was condemned as a patchy affair by several critics on release in 1966, in retrospect it clearly threw open the gates to yet another influential genre – psychedelia.

The use of mind-bending drugs was being widely advocated by radicals in the underground arts community from the early 60s. Early references to psychedelia and LSD cropped up first in tracks by two Greenwich Village avant-garde folk bands – The Holy Modal Rounders and The Fugs. By the end of 1965, several artists – The Psychedelic Rangers, Malachi, Kim Fowley and others - were applying the term psychedelic to their music.

It was Fifth Dimension, however, which presented the world with its first fully-realised psychedelic rock songs – notably Eight Miles High, 5D, What's Happening, I See You and 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song).

So when I interviewed Byrds' leader Roger McGuinn for this feature, my first priority was to establish whether or not they had deliberately set out to invent psychedelic music. "Not at all," he replied politely but firmly. "We were just trying to make a varied set of tracks that would work together as an album and, because of the various influences within the band at the time, for example our exposure to John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar, some of the tracks just came out that way. Then, because of what was going on all around, our listeners interpreted what we did as psychedelic."

The atmosphere within the group around the time of the recording sessions was not good. Gene Clark, partly because of a fear of flying, had quit the group and David Crosby was looking to increase his role within the hierarchy. "Gene refused to fly to a tv show in New York," explained McGuinn. "He just got off the plane in LA, and that was it. Crosby was also getting a little bit antsy. He was worried that he wasn’t getting enough of his own songs on the album, so there was tension building."

Before Clark's departure, however, he contributed significantly to the writing and recording of Eight Miles High, which would become the album's first single. "A friend of Crosby’s had a copy of John Coltrane’s latest album, which had that little melody line we used for the opening of the lead guitar part in Eight Miles High. We made a tape of it and listened to it over and over again on our tour bus until it saturated us. By the time we got back to LA to start recording it was kind of ingrained. I’d been practising jazz and blues scales a lot so that thing just came out."

Two versions of Eight Miles High were recorded, but the first, from December 22, 1965, was rejected by Columbia Records, largely because the band had used their manager Jim Dickson as producer. Columbia house producer Allen Stanton was brought in to oversee a new version, taped on 25 January 1966. It has gone on to be recognised as an all-time classic rock single, but David Crosby has always asserted that the original was even better, saying, "It was stronger, it had a lot more flow to it. It was the way we wanted it to be."

McGuinn now concedes that Stanton (who produced the rest of the album as well) was not a satisfactory collaborator for The Byrds, and that his contributions to the sound of the album were minimal.

The next track laid down was the whimsical Mr. Spaceman, a light-hearted country-flavoured novelty item about an alien encounter. McGuinn describes it as, "one that just sort of arrived. It's a silly song but I just started playing guitar one day and got a series of chords that I liked and hooked up a melody to it. And then I was looking out the window and kind of fantasizing about a flying saucer landing out there in the front yard. The song came out in probably about thirty minutes."

Crosby weighed in at an April 29 session with the first of what would prove to be many metaphysical ruminations, What's Happening?!?!. With its doom-laden descending bass pattern and trippy guitar lines, it's very much one the album's pioneering psychedelic triumphs. "It asks questions of what's going here and who does it all belong to," he has explained. "Each time I ask the questions, McGuinn answers them on the 12-string. He says that same thing with the instrument musically."

Another ground-breaker was 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song), recorded on May 3. Arguably a knock-off novelty, it nevertheless boldly incorporated documentary audio footage of a Lear Jet taking off and in flight, complete with radio talkback, against a minimalist Rickenbacker riff and an even more minimal one line lyric, "Go 'n ride the Lear Jet, baby". If Kraftwerk had done this a decade later, it would have been hailed as genius.

In a burst of studio activity between May 16 and May 25, the rest of the album came together quickly, including the deeply moving anti-nuclear anthem I Come And Stand At Every Door, based on a Nazim Hikmet poem set by McGuinn to the melody of the folk ballad Great Selchie Of Shule Skerry. On May 17, Crosby achieved his long-held ambition to do a speedy version of Billy Roberts' Hey Joe, a staple of the Los Angeles club scene at the time, and the powerful but inconsequential bluesy instrumental Captain Soul was taped the next day. "God knows what they had on their minds," said bassist Chris Hillman when asked about Captain Soul. "How embarrassing."

Further evidence of Crosby's increasing maturity as a songwriter came on May 19 with the jazzy changes and enigmatic lyric of I See You, after which the album's masterful opening cut, 5D (Fifth Dimension) was recorded on May 25.

Like Eight Miles High, 5D's dreamlike lyric added fuel to accusations that The Byrds were promoting drug use but McGuinn is adamant that this was not so. "I had read a book, 1-2-3-4, More, More, More, More," he reveals, "which was about the possibility of additional dimensions beyond time and space. That's what I was singing about."

The Bach-like organ part in the track was supplied by young session player Van Dyke Parks who would, of course, go on to collaborate with The Beach Boys before establishing his own acclaimed solo career.

On the same day, perhaps anxious that they had left their signature folk-rock sound too far behind, they recorded the traditional songs Wild Mountain Thyme and John Riley, both using simple but effective string arrangements by Allen Stanton.

One anomaly remains the decision to leave a much-loved Byrds artefact, Why (recorded on 24 January), off the album. Sonically, it's an ideal companion piece to Eight Miles High, and its inclusion would have made Fifth Dimension a significantly stronger whole. McGuinn says he cannot now recall why it was not chosen, but seems to suggest it was considered too similar to other tracks. "We made a conscious decision to get out of the folk-rock box into new areas," he says, "We didn’t want to be categorised in one musical genre."

Released on March 16 as the album's first single, Eight Miles High failed to achieve the chart status that could have spurred massive sales for Fifth Dimension. The widely-held perception that it was promoting the use of drugs meant that many deejays refused to play it. McGuinn stated then, and still insists today that, "Lyrically it was about the airplane ride to England for our first tour and the cultural shock we experienced when we got there. Yes, we were doing drugs, but Eight Miles High Wasn’t a commercial for it. Some people put together the word ‘high’ with our appearance and came to a rather superficial conclusion."

Fifth Dimension was released by Columbia on July 18, 1966, and influential critic Jon Landau of Crawdaddy! magazine spoke for many critics when he declared that it "cannot be considered up to the standards set by The Byrds' first two." It went on to peak at No44 on the Billboard Hot 100 but completely failed to chart in the UK

Widely misunderstood on release, Fifth Dimension has grown in stature over the decades and is now regarded as a watershed album of the 60s.

------------------------------------

PRODUCTION NOTES

by Johnny Black

By the time of Fifth Dimension, The Byrds were recording on 8-track but McGuinn chuckles when he recalls, "The 8-track recorders had been in the Columbia studio for ages but the staff were very conservative about new equipment, so the machines were stuck in a corner with a sign hanging on them indicating that they should not be used."

Perhaps the most distinctive advance in the sound of Fifth Dimension, though, was the sound of McGuinn's 12-string Rickenbacker which previously had been employed to create a folksy chiming accompaniment. On tracks like Eight Miles High, What's Happening?!?! and 5D, however, it had metamorphosed into a futuristic wail of passion.

The route to this sound began back in 1965 during the recording of Mr. Tambourine Man. In McGuinn's own words, "The 'Ric' by itself is kind of thuddy. It doesn't ring. But if you add a compressor, you get that long sustain. To be honest, I found this by accident. The engineer, Ray Gerhardt, would run compressors on everything to protect his precious equipment from loud rock and roll. He compressed the heck out of my 12-string, and it sounded so great we decided to use two tube compressors in series, and then go directly into the board. That's how I got my 'jingle-jangle' tone. It's really squashed down, but it jumps out from the radio. With compression, I found I could hold a note for three or four seconds, and sound more like a wind instrument. Later, this led me to emulate John Coltrane's saxophone on Eight Miles High. Without compression, I couldn't have sustained the riff's first note."

The album's closing track, 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song) was arguably the album's other most innovative recording for the way in which it mixed a location recording, on a portable Ampex tape recorder, of jet noises throughout the entire track, and placed it very high in the mix. Many have dismissed it as a simple gimmick but, from the start, David Crosby always championed the song describing it as "another direction we've gone into. We've mixed the sound of the jet and the sound of the people talking on the radio and the sounds of the instruments – all the sounds you would go through if you were taking off in a Lear jet."

Sound effects and found sounds had been used in popular music earlier, such as the rattling chains and creaking coffin in 1962's Monster Mash by Bobby 'Boris' Pickett And The Crypt-Kickers or the seagulls and crashing waves in 1964's Remember (Walking In The Sand) by The Shangri Las. However, by elevating the jet recording from a simple background sound effect to an integral part of the entire track, The Byrds were in tune with the most avant-garde composers of the era.

---------------------------------------

THE BYRDS QUOTES ABOUT FIFTH DIMENSION

Chris Hillman : I didn't contribute much, but Fifth Dimension, the song, is one of my all-time favorite McGuinn songs. And I've said this for years. I think Fifth Dimension's one of the better songs he's ever written and sung. I love that tune. I think that Roger and I got more as a team in Notorious Byrd Brothers, when we started to play around in the studio with stuff. Prior to that, [the most psychedelic Byrds records] that was more Roger's deal. I would play on it, but it wasn't something I was involved in, other than as the bass player. And he had that side of him, musically, that was not my style of music. It really wasn't something that I loved that much. But I was a player, and that's his piece of material, so I supported it. But I sort of dragged him into the country stuff, so it works both ways. And he performed quite well with that stuff.

(SOURCE - Interview with Richie Unterberger ca. 2000)

Chris Hillman : It was 1966. While in the Byrds, we were doing a session recording the track Eight Miles High. I thought we (all members of The Byrds) took a huge left turn musically by recording that song, which of course, has been redone on my latest album, The Other Side. It should've been a top 10 or number one single back then. However, it was labeled as a drug use song by the critics - which was untrue. It was really about flying to London in 1965 for the very first time. As a piece of music, that was radically a departure from what we were accustomed to.

(Source : interview with David Strickler 2007)

Roger McGuinn : Well, the song ('Mr.Spaceman') lends itself to that type of thinking because it is silly in the middle. Blue-green footprints that glow in the dark is a silly line and I sort of regret putting that in there, but I was trying to put out my feelings. I had just read a flying saucer book or two, or three, or four and I had just gotten into flying saucer books, testimonials -- highway patrol officer so-and-so was driving down highway such-and-such and he saw this orange light come in front of him and his car stopped and he got out and flashing red lights came on. Like all those books have the same reports in them basically. Some of them are real and some of them aren't. Incidentally, I'm glad they closed up Project Blue Book. Nobody's recorded any flying saucers lately, have they?

(Source : interview with Vincent Flanders, 1969)

Roger McGuinn : Some songs are more studied and more calculated. Others songs just pop into your head. Mr. Spaceman was one that just sort of arrived. It's a silly song but I just started playing guitar one day and got a series of chords that I liked and hooked up a melody to it. And then I was looking out the window and kind of fantasizing about a flying saucer landing out there in the front yard. The song came out in probably about 30 minutes.

(Source : Reveries 2001)

Roger McGuinn : Technically it (Eight Miles High) should have been six miles high, but six miles high didn't sound as good poetically.

(Source : interview on BBC London, 2009)

Roger McGuinn : I think (in the 5D era) maybe we got too much flack for doing too many Dylan songs.

It was basically the fact that he (Gene Clark) was kinda fried. He was burned out and the fear of airplanes was just all of it coming to a head. He also had an ambitious streak, and he wanted to go off as a solo artist. Pickner and Dickson were grooming him to be the Elvis Presley. So, there was another sort of ...a sinister plot. It didn't work out.

We decided to stay with four. We talked to the Beatles and they said that they had had five guys and they liked being four better. We said if it was good enough for them, it was good enough for us.

He (Chris Hillman) was a little shy, but he grew into it. Over the years, he's really gotten good. He's a real melodic bass player.

Those ('Wild Mountain Thyme' and 'John Riley') were my arrangements.

It's ('I Come And Stand At Every Door') a Pete Seeger influence. I got it from a Pete Seeger record. He had always been an influence and an inspiration to me, and I thought I'd put it on there. Actually, Pete asked me where I got it, too.

That's ('I See You') an early sessions, bubblegum type of song. I did like the jazzy kind of feel to it.

I'd been playing around with that jazz, Coltrane type of influence. It kinda seeped into everything I did at that point.

I have no idea why it ('Why?!') was omitted.

I think the RCA (version of 'Eight Miles High') has a little more fire, but I think we had been practicing it enough by the time we got into the CBS studio that it came out a little cleaner. It got a little more musical tightness. They both have merit.

The Gavin Report knocked it out.

It's funny, but I remember we were dealing with a female DJ in New York City. When the single came out, we played it for her and she said, "Oh. Where's the single?" I said, "That is the single." She just shook her head, like, "Yuch.

It was getting up the charts. It was up to number twelve or something. It would've gone to the Top 10. It was pretty abstract.

Gene came up with the chord changes, for the initial verses. And, Gene and I worked on the lyrics -- it was my idea to make it about the airplane ride over to England, and so we kinda worked on the lyrics. And Crosby helped with that, and then, basically, that was it. Then I did the guitar work. It was a Gene-rooted song, but Crosby and I helped.

It's ('I know My Rider') an old folk song. We all knew it from playing around in the Village in different coffee houses.

(Source : musicangle 2004)

Chris Hillman : There's things I'd never heard before. I'd forgotten we'd put an organ on the song 5D - by the way, [that's] one of the greatest songs Roger McGuinn has ever written. He'd probably never admit that. That's one of the best songs - I love that song. It just swings like a big pendulum. And the other thing, I'm throwing these at you and you can assemble them later, but Michael Clarke got so much bad press as a drummer, and he was an undisciplined drummer, but there were moments when he zapped. You know, "Eight Miles High," he was wonderful. A lot of songs, he was great on. I listened to them and I just went, "God."

David plays great rhythm.

The state of affairs with The Byrds and having been out on the road, and playing after a year or so. "8 Miles High," of course, we'd been listening to John Coltrane and we'd been on a Dick Clark rock and roll tour, and we constantly had music on our RV. We were between John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar at that point. In fact, we did 5D after that particular road trip, and we took that left turn. We didn't sit down and say, "let's do this." It just happened. "8 Miles High" was about that trip to England, and Gene once again comes up with this great imagery - exactly to the point, of when you touch down, blah blah blah, describing London and the summer. It was cloudy, we were tired, it was just a very interesting end result of that tour.

Well, he (Gene Clark) was under a lot of pressure. That was just part of it, I think. I don't think he liked flying, but that was part of it. There was a lot of pressure, and he wasn't happy and I think there was some dissension among the other principal singers at the time, and it just got to him. He had problems before that, it just ... he was a great guy. Here's this very nice kid from Kansas, but I think Hollywood, of all the cliched things, just ate him up and spit him out. I think Gene probably would have had a really good life in the Midwest. But, I don't know. He was just a tortured guy, from the getgo. It's too bad. He left, and then I tried singing.

It was nice to be out in the front and do that (singing), and it was also hard to do it for a while, but it was good. The door opened and I sort of took advantage of it. I didn't take advantage until the next record, you know, after 5D.

I wasn't really singing much, other than doubling Roger. See, what Gene did was double Roger, there wasn't really a three, distinct tenor-baritone lead, there was just two leads and David. It was interesting because the voice that came out of Roger and Gene was interesting. But, that's basically it. They didn't do the same parts; I don't know why. Because when we went in to do the box set, we did three-part on "He Was A Friend of Mine" and everything else.

Well, that's ('Hey Joe') okay. I think that David did it really good, but I don't remember. I think that I don't take it as seriously because the Lees, kind of this Byrds-clone, put it out. It was one of David's songs he always did. David probably did that when he was a folk singer when he was solo, before The Byrds. I'm sure he did. I'd guarantee it. I think David did it as a soloist and brought it in and we worked it out electrically, then Hendrix did it. Hendrix did it great. Really, really, interesting.

I don't even remember the words to "The Lear Jet Song." Let's file that under "novelty." "Captain Soul ..." God knows what they had on their minds ... how embarrassing. This album, I think there are two or three really good, interesting tunes, led by "8 Miles High" and "5d." The rest were just scattered. I don't think we knew what we were doing. I think we were just about either in a management change or something with Gene leaving.

I think the RCA (version of 'Why?!') is better -- I think it flows better. Once again, Mike was really interesting on this song. We were coming off of a road trip listening to John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar, and John Coltrane comes out through the "8 Miles High" situation. "Why" comes out through a lot of Ravi Shankar, and it's great. I love it. It's a neat song. Since we were doing "Why" in the Victor thing too, it might stand that the "8 Miles High" from RCA is better, along with that track.

That's ('I Know My Rider') an old folk song that we were just kicking around. Everybody used to sing that in the old folk days.

It's just a song ('John Riley') that Roger wanted to put on and I didn't care for it too much. He's into that kind of material to this day. He does it really well -- just a different style of stuff than I'm used to doing.

(Source : Musicangle 2004)

David Crosby : But Fifth Dimension and Younger Than Yesterday, where we really actually started to shine, I don't think they had producers did they?

Yes, he (Allen Stanton) was Columbia's idea of just having someone there to make sure we didn't [hurt] the place.

Other people were telling him (Gene Clark) he could be the next Elvis and that he was... you know, that he didn't... the standard thing...the same shit that fucking Yoko whispered in John's ear 'you don't need those guys, you're a star'. Jesus Christ, think about it. The two guys who could have had any two women on earth...... My god!!! And Gene was afraid of airplanes. We were going to a gig, we all got on the airplane he was very very nervous, he'd probably gotten himself chemically enhanced before he got on and he was sitting there and he too high or whatever it was, he panicked and got off the plane. And Roger's response was 'if you can't fly, you can't be a Byrd.'

Gene was never meant for that man. If Gene had instead gone to Nashville, he probably would have been a huge star because he was good looking- a good looking young guy. A good singer and a good writer and he had a charisma, you know? He was a great guy.

We were on tour. We were out. We were all pot smokers, so we couldn't ride on the regular bus with everybody else. We got a Winabago and drove it ourselves. And in the course of driving the Winabago one night we're driving from one town to another and Gene comes butt surfing up to the front of the thing and says 'I've got this song started' and he had part of the second half of the verse. So I came up with the chords to the 'eight miles high' part. And he came up with the other part. And he had words and we started working around with the words- all of us contributed to it. I came up with "rain gray town" and some other things and Roger came up with some other stuff. It was the first song we organically wrote together that freely that well and while we were on that tour I kept playing a tape machine- a reel to reel machine- hooked up to a Fender amplifier and we were playing John Coltrane's Africa Brass and if you listen to it you'll find on either "India" or the title track, you'll hear where the McGuinn solo came from. The opening notes are a straight cop from a Coltrane solo. It was really powerful music and it affected all of us. This wild, crazy, beautiful music.....And then they took it off the air!

Yea, there was a newsletter guy who took this big stand that that song and "Rainy Day Women" (everybody's gotta get stoned) had to go because they were breaking down our moral fiber....

Yea, that ('Why?!') came from me playing Ravi Shankar in McGuinn's ears for years. I turned everybody I could find onto that. I did that for a long time. George (Harrison) credits me with turning him onto it I think. I did that for a long time and then I did that with that women's Bulgarian folk Choir.

(Source : - Musicangle 2004)

Gene Clark : (About Eight Miles High): I had an idea for some lyrics and wrote them on a piece of paper during the conversation with Brian. Later on I found them in my jacket pocket on the tour bus. I took my guitar and started making up a melody for it. I pretty much completed the song and played it for McGuinn and Crosby, and they really liked it. There were a lot of images I got from thinking and remembering things we'd done on the English tour. Actually, I started the thing before we got to England, and finished it when we got back. We were listening to a lot of Coltrane and Shankar. I felt that the arrangement idea McGuinn came up with alone deserved co-writer credit on it. Crosby, as well, came up with some of the lyrics. I kinda felt that all three of us wrote the song.

(Source : Cosmic American Music News, 1992)

Gene Clark : I wrote all the words (to Eight Miles High) except for one line that David wrote (Rain grey town), and then Roger arranged it, basically, so I had to part something with those guys.

I decided that I wasn't going to get a single out of this deal, because I'd already written so many songs with this group that they're gonna grab up the singles for their own stuff, you know so I split it with them so I could get a single. That and they really did help me write it, too. But one of the problems we had by the release of the second album was the animosity growing amongst the group. Especially about me, because I was making a lot more money than anybody else from the royalties.

(Source : Interview with Chris Hollow, 2000)

David Crosby : We first cut the song (Eight Miles High) at RCA studios with Dave Hassinger (a producer). It was fantastic! The song just took off. But we'd done it secretly, without Columbia's approval. So they made us redo it with union nerds. The record company slapped our hands if we tried to touch the board. It was a shame. The version that got released was'nt nearly as good.

It (Why?) was all mine. That was one of the first songs I ever wrote that I really liked. It was saying something and questioning.

(Source : Crosby, Stills And Nash Biography, 1984)

Roger McGuinn : What I'm talking about is the whole universe, the Fifth Dimension, which is height, width, depth, time and something else. But there definitely are more dimensions than five. It's infinite. The Fifth Dimension is the threshold of scientific knowledge. See, there are people walking around practicing fifth dimensional ways of life and the scientists are still on two or three dimensional levels. There's a conflict there. A lot of our world is very materialistic and scientific. It overlooks the beauty of the universe. That's what the song is about. Maybe I'll tell a few people what's going on in life.The organ player on it is Van Dyke Parks. When we came into the studio I told him to think Bach. He was already thinking Bach before that anyway.

(Mr. Spaceman) began as a serious, melodramatic screenplay. I thought the song being played on the air might be a way of getting through to them (friendly aliens).

(On Eight Miles High) we were playing 12-string Rickenbacker to sound like a saxophone. We were translating jazz into a rock form.

Gene said eight miles high sounded better than six and it did sound more poetic. It was also around the time of 'Eight Days A Week' by the Beatles, so that was another hook..

The reason Crosby did lead vocal on 'Hey Joe' was because it was his song. He didn't write it but he was responsible for finding it. He'd wanted to do it for years but we would never let him. Then both Love and the Leaves had a minor hit with it and David got so angry that we had to let him do it.

Essentially, it (Captain Soul) was Mike Clarke's trip. He wanted us to do something soul-oriented, so we did that for him.

(Source : CD Liner Notes, 1996

David Crosby : It's a very strange song (What's Happening ?!?!). It asks questions It asks questions of what's going here and who does it all belong to and why is it all going on. I just ask the questions because I really don't know the answers. Actually, each time I ask the questions McGuinn answers them on the 12-string. He says that same thing with the instrument musically. You can tell it, you can feel it.

(The RCA cut of Eight Miles High) was stronger. It had a lot more flow to it. It was the way we wanted it to be.

(Source : CD Liner Notes, 1996)

David Crosby : I'm a better harmony singer than Roger. That was my gift. I could complement Gene's songs very well. But that had a lot to do with the nature of Gene's songs. Gene wrote changes that lent themselves to my kind of nonparallel, contrapuntual kind of harmony. One of the reasons the Byrds did what they did, sounded the way they sounded, was that if you have three parts, all the places to move are taken up. So you can really only move the three parts basically parallel. It takes a lot of effort to get them not to be parallel. Crosby, Stills & Nash managed that, but almost nobody else. Other than that, when you hear three voices, they're mostly moving parallel. If you have three, then one's on the top and the other one can move around between the third, the fifth, the fourth, the sixth. The other one has all the room to move, to create that tension by the relationship between it and the melody. And because just about all the Byrds' harmony was two-part, I had room to move. So my harmony could become a second melody and that creates emotional tension. It just does. For example the melody in 'Eight Miles High'. You can't do that in three-part, it's much more difficult.

It ('Eight Miles High') was my favourite moment. It was when we actually started to come into our own.

(Source : interview with John Einarson, Mr. Tambourine Man, 2005)

Gene Clark : I had an idea for some lyrics (Eight Miles High) and wrote them on a piece of paper during the conversation with Brian (Jones of the Rolling Stones). Later on I found them in my jacket pocket on the tour bus. I took my guitar and started making up a melody for it. The initial idea was discussed on the plane over the Atlantic on our trip to England, but the actual writing of it started on a tour with the Stones when we were back in the States.

(Source : interview with John Einarson, Mr.Tambourine Man, 2005)

Gene Clark : I started writing a poem that didn't have any music. And the poem had words to it like ' Eight miles high, and when you touch down, you find that it's stranger than known'. I was into it because I was writing about a trip we had just done to England and the culture shock going over there and being very famous and having to live up to that. So I just came up with a couple of chords to play the poem to Roger and David with. We had been listening to these tapes of Indian music, Ravi Shankar, and John Coltrane all this time because we enjoyed listening to that kind of music, it was good travelling music. And Roger, I remember, suggested, 'Well, why don't we take that poem and put it to this kind of jazz rhythm and do the kind of Coltrane licks in it' because it was so into our heads. So then David came in and said 'Yeah, that sounds good. Let's arrange this', and it ended up the three of us collaborating on the song and that became 'Eight Miles High', which was the influence that we got from Coltrane's 'Africa Brass' and 'India'.

I wrote all the words except for one line that David wrote ' Rain gray town, known for its sound' and then Roger arranged it, basically, so I had to part something with those guys. There were a lot of images I got from thinking and remembering things we'd done on the English tour. I decided that I wasn't going to get a single out of this deal, because I'd already written so many songs with this group that they're gonna grab up the singles for their own stuff, you know, so I slit it with them so I could get a single. That and they really did help me write it, too.

(Source : CHUM Radio Interview, Toronto, 1978)

Roger McGuinn : I think I wrote some of the words (for 'Eight Miles High') too. Gene didn't have it all done. First of all it was my idea to write it about the airplane, the 'eight miles high and when you touch down' was my idea. It wasn't a done song. We kind of said 'What'll we write about?' because Gene had the chords, the changes, the Em, G, D and C. I think I might have come up with the C down to Am thing because that was like a Bob Gibson riff I used to do. So it was a collaborative effort. In hindsight, I think Gene kind of gave himself more credit for it. He was upset at one point about a song we did later in McGuinn, Clark & Hillman and said 'I'm not going to let this happen again where you guys get credit for a song I wrote'.But it's not totally true. We really did collaborate on it. I can't give you specifically who wrote what lines but I know I was involved in the writing process as well.

We listened to it (John Coltrane's 'India') so many times over and over that when we got back to the studio in L.A. it was steeped into us and we started playing that kind of music. The guitar break was obviously a tribute to John Coltrane. That's one of my favourite guitar things I've ever done.

(Source : interview with John Einarson, Mr.Tambourine Man, 2005)

Gene Clark : It ('Eight Miles High') was about lots of things. It was about the airplane trip to England, it was about drugs, it was about all of that. A piece of poetry of that nature is not limited to having it have to be just about airplanes or having it have to be just about drugs. It was inclusive because during those days the new experimenting with all the drugs was a very vogue thing to do, so people were doing all that at that time. All that was kind of in the poetry. But it has meanings of both. It's partially about the trip and partly about drugs.

(Source : interview with Domenic Priore, 1985)