Fact #79165

When:

Short story:

On the seventh night of a season at The Apollo Theater, Harlem, New York City, USA, James Brown records a live set which will become his classic album Live At The Apollo (Vol 1). Also on the bill are Freddie King, Solomon Burke, Pigmeat Markham and The Valentinos.

On the seventh night of a season at The Apollo Theater, Harlem, New York City, USA, James Brown records a live set which will become his classic album Live At The Apollo (Vol 1). Also on the bill are Freddie King, Solomon Burke, Pigmeat Markham and The Valentinos.Full article:

VINYL ICON FEATURE

JAMES BROWN LIVE AT THE APOLLO (1962)

Live At The Apollo is the frenzied, sweat-drenched aural-sex workout which, in 1962, not only catapulted James Brown to the forefront of the rapidly evolving soul music scene, but also paved the way for the birth of funk.

Brown was a street-tough kid, raised by an aunt in Augusta, Georgia. Arrested at 16 for breaking into cars, he was headed for a life of crime until, in 1952, gospel got him interested in music and one year later a Little Richard performance turned him on to rock’n’roll.

He found huge success in 1955 with the hit single Please, Please, Please, but by 1962 he was already abandoning the familiar riffs of blues and r’n’b, drilling his band like a military machine to create syncopated dance riffs punctuated by razor-sharp horn blasts - blissfully unaware that he was establishing the blueprint for what would come to be called funk.

He was the biggest-selling artist on Cincinnati’s King Records, but when Brown pitched the idea of a live album to King’s boss, Syd Nathan, the response was, "You want to do it, you spend your own damn money. You ain’t gonna spend mine."

Nathan, understandably, felt that the fans wouldn’t shell out their hard-earned cash for live versions of songs they already owned. Brown, however, knew that the live presentation of those songs was now radically different from the versions he had originally recorded. "I needed to let people know that what was really happening was The James Brown Show live!"

Brown’s conviction stemmed from the fact that Ray Charles had achieved a Top 20 placing in 1960 for his live album, In Person. Knowing this, Brown concluded that an in-concert release could reveal the excitement of his super-charged stage shows to an audience which only knew him through his inevitably more clinical studio recordings.

"I wanted the feeling of tent meetings, when you got the spirit going at gospel conventions," Brown declared subsequently.

Brown’s musical director, Bobby Byrd, has recalled, "None of the company executives believed us, but see, we were out there. We saw the response as we run our show down."

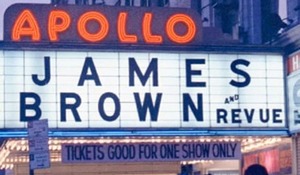

Already being nicknamed Soul Brother No1, Brown was so sure of himself that he borrowed $5,700 to finance a live recording of his upcoming show at the 1500 capacity Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York City.

Situated at 125th Street and Eighth Avenue, it was originally a Vaudeville burlesque house, but had become a showplace for black entertainers in 1934 when the city authorities clamped down on its risqué burlesque shows. By the sixties, it had become the jewel of what was known as the Chitlin Circuit - the collective name given to a chain of venues in which African-American musicians, comedians, and others could perform while racial segregation still blighted the USA.

Brown and his band had been selling out all across the Chitlin Circuit, so it made perfect sense to record the live album at the finest of them - The Apollo.

Brown was a hard taskmaster, and it had long been his practice to fine band members $5 or $10 for every mistake made during a gig, but he placed such importance on the success of the Apollo show that he warned every member of his band in advance that any mistakes on the big night would be punished with a $50 to $100 fine.

The schedule was punishing, with the fourteen-piece James Brown Revue playing five performances every day for a week, leading up to the final show on October 24, which would be recorded for the album.

"We had opened on the 19th," recalled Brown later, "and were building up to recording on the 24th which was Amateur night. I wanted that wild Amateur Night crowd because I knew they'd do plenty of hollering."

Booking agent Jack Bart has recalled that, "It was freezing cold that day. Still, the ticket holders' lines stretched around two corners. It was incredible. Brown's people gave out free cups of coffee for everyone standing and waiting."

The show they got was impressive, headlined by Brown but also featuring Solomon Burke, Texan blues guitar maestro Freddie King, Sam Cooke proteges The Valentinos (featuring Bobby Womack and his brothers) and popular comedian Pigmeat Markham.

The Apollo stage was built of well-worn wooden planks and, from the crowd’s perspective, it resembled little more than a box twice as wide as it was tall.

Knowing how important the recording could be, Brown, Byrd and the rest of the company were anxious as showtime approached. King Records’ Vice President Hal Neely brought the live tapes backstage for them to hear between shows, enabling them to further refine the set as the day progressed.

In the words of Bobby Byrd, "There was tension, you know, we were nervous about recording and all. But the minute we hit the stage … magic!”

Emcee Fats Gonder primed the already hyped-up audience with a lengthy rant that began, "So now, ladies and gentlemen, it is Star Time. Are you ready for Star Time?!" Their screams and howls confirmed they were more than ready - they were gagging for it.

In his autobiography, Brown confirmed Byrd’s assessment. "As soon as I was into I’ll Go Crazy I knew it was one of those good times. That’s a hard feeling to describe - being on stage, performing and knowing that you’ve really got it that night."

Brown and his band, tightly drilled by trumpeter Lewis Hamlin, pounded out the hits, I’ll Go Crazy, Please Please Please, Night Train and the rest, with one outstanding highlight being a lengthy gospel-soaked Lost Someone, before climaxing the show with a nine-hit medley after which Brown quit the stage to the sound of a rampaging Night Train.

Although the show was a major triumph, the perfectionist in Brown was still not 100% satisfied. "Every now and then, the band made a mistake or The Flames were a half-tone off", he stated later.

Syd Nathan had been reluctant to allow the live recording from the start and, when he heard the completed tracks, he was still not keen to release the LP.

Nathan’s usual modus operandi was to release a few singles and see if any of them started to take off before risking an entire album. Thus, according to Brown, "He didn't like the way we went from one tune to another without stopping … I guess he was expecting exact copies of our earlier records, but with people politely applauding in between."

By fielding a string of petty objections, Nathan managed to delay release for almost eight months, and when it finally went on sale in May 1963, his conviction that it would not sell was evidenced by the fact that King Records’ initial pressing amounted to a mere 5000 copies.

In strictly business terms, Nathan’s approach was completely rational and understandable, but Live At The Apollo was anything but business as usual. The album was offering fans a visceral, overpoweringly emotional experience that defied conventional logic. The Billboard album charts at that time were dominated by MOR artists (Johnny Mathis), polite folkies (Peter, Paul and Mary), comedians (Allan Sherman) and soundtracks (West Side Story), bought by consumers who had probably never even heard of James Brown.

What Nathan did not understand was that times were changing. There were stirrings of racial integration, black consumers and white teenagers both had a little more folding money in their wallets, and with rock’n’roll languishing in the doldrums, there was a potentially huge, unsatisfied audience out there longing for music with considerably more spunk and guts than MOR pop could offer.

Imagine Nathan’s surprise then, when radio picked up on the album. "We played cuts from it during the day," explains disc jockey Rocky G of New York station WWRL. "But in the evening we had to play the whole thing, all the way through. People were always calling in, saying 'Play James Brown Live At The Apollo.'" And WWRL was not alone. The album caught fire right across America.

Spending a staggering 66 weeks on Billboard’s pop LP chart, it peaked at No2, held off the No1 slot ironically enough by an album which was its polar opposite - Andy Williams’ Days Of Wine And Roses.

Live At The Apollo earned James Brown the title of the Hardest-Working Man In Showbusiness and proved, in a wider context, that in-concert albums could be very good for business indeed, attracting a vast new audience to an already established artist.

Over the years, the status of Live At The Apollo has grown to such an extent that it is now routinely included in virtually any chart or listing of all-time essential albums. It is also cited as a prime influence on the output of later artists as diverse as The MC5, The Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson and Public Enemy.

Technically, Live At The Apollo is not a great-sounding record but it is an irreplaceable document of a truly great, innovative and soulful artist at the peak of his powers. What more do you want?

VINYL ICON - PRODUCTION NOTES

JAMES BROWN LIVE AT THE APOLLO

According to the original sleeve notes, this album was recorded "in Stereophonic Sound using AMPEX 350-2 tape machines. According to James Brown himself, it was done with portable Magnacorders - rare items at that time - rented from A-1 Sound in New York, to enhance the venue’s in-house PA system, mixer and mics.

Brown paid for the whole enterprise, so I’m inclined to trust his version of events, especially as those sleeve notes also listed the highly reputable Tom Nola of New York’s Nola Penthouse studio as engineer, but King Records’ Vice President Hal Neely claims to have engineered it, a fact which Brown confirmed in his autobiography, declaring, "He worked on the tape a long time and did a fantastic job of mixing it." Again, the Brown version makes sense, because although revered as a jazz producer, Nola did not enjoy rock’n’roll and usually farmed such work out.

What seems somewhat more reliable is that the recording used eight microphones, two of which were placed to capture audience response, but all of them fed into a 2-track recorder so 'mixing’ was a minimal process at best, probably limited to the engineer monitoring the recording on headphones, turning the audience mics down when the crowd was cheering, and up again during the bulk of the song.

One delightful anecdote involves a 70 year old old lady who was captured shouting, "Sing it, motherfucker, sing it", during a quiet interlude in Lost Someone. Neely, it seems, had strung up one of the audience mics on a wire between two side balconies, and it happened to be directly above the foul-mouthed old dear. Neely himself didn’t discern what she was shouting until he played the tape to the band backstage, and saw them collapsing in hysterical laughter. When they explained, Neely panicked and his first response was to find some way to exclude her voice from the tapes.

The band, however, thought it was very amusing, and prevailed on Neely to find a compromise of some sort. "He fixed all the cussing so it wasn’t right up front," explained Brown. "He figured it would be an underground thing for people who knew what the lady was screaming. He was right too."

When Neely’s carefully edited tapes were sent to chief engineer Chuck Seitz at King Records in Cincinnati, he detected another problem. "They had very, very little audience on them. I suggested we try to boost the audience up. I went out to Roselawn, to a dance they used to have out there, with a tape recorder. I knew the DJ, so he got them to applaud and cheer and I went back and inserted it where it was needed." As a result, most of the audience response on the original album comes from people who weren’t actually at the show.

This feature by Johnny Black first appeared in Hi Fi News - March 2017)

Tweet this Fact

JAMES BROWN LIVE AT THE APOLLO (1962)

Live At The Apollo is the frenzied, sweat-drenched aural-sex workout which, in 1962, not only catapulted James Brown to the forefront of the rapidly evolving soul music scene, but also paved the way for the birth of funk.

Brown was a street-tough kid, raised by an aunt in Augusta, Georgia. Arrested at 16 for breaking into cars, he was headed for a life of crime until, in 1952, gospel got him interested in music and one year later a Little Richard performance turned him on to rock’n’roll.

He found huge success in 1955 with the hit single Please, Please, Please, but by 1962 he was already abandoning the familiar riffs of blues and r’n’b, drilling his band like a military machine to create syncopated dance riffs punctuated by razor-sharp horn blasts - blissfully unaware that he was establishing the blueprint for what would come to be called funk.

He was the biggest-selling artist on Cincinnati’s King Records, but when Brown pitched the idea of a live album to King’s boss, Syd Nathan, the response was, "You want to do it, you spend your own damn money. You ain’t gonna spend mine."

Nathan, understandably, felt that the fans wouldn’t shell out their hard-earned cash for live versions of songs they already owned. Brown, however, knew that the live presentation of those songs was now radically different from the versions he had originally recorded. "I needed to let people know that what was really happening was The James Brown Show live!"

Brown’s conviction stemmed from the fact that Ray Charles had achieved a Top 20 placing in 1960 for his live album, In Person. Knowing this, Brown concluded that an in-concert release could reveal the excitement of his super-charged stage shows to an audience which only knew him through his inevitably more clinical studio recordings.

"I wanted the feeling of tent meetings, when you got the spirit going at gospel conventions," Brown declared subsequently.

Brown’s musical director, Bobby Byrd, has recalled, "None of the company executives believed us, but see, we were out there. We saw the response as we run our show down."

Already being nicknamed Soul Brother No1, Brown was so sure of himself that he borrowed $5,700 to finance a live recording of his upcoming show at the 1500 capacity Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York City.

Situated at 125th Street and Eighth Avenue, it was originally a Vaudeville burlesque house, but had become a showplace for black entertainers in 1934 when the city authorities clamped down on its risqué burlesque shows. By the sixties, it had become the jewel of what was known as the Chitlin Circuit - the collective name given to a chain of venues in which African-American musicians, comedians, and others could perform while racial segregation still blighted the USA.

Brown and his band had been selling out all across the Chitlin Circuit, so it made perfect sense to record the live album at the finest of them - The Apollo.

Brown was a hard taskmaster, and it had long been his practice to fine band members $5 or $10 for every mistake made during a gig, but he placed such importance on the success of the Apollo show that he warned every member of his band in advance that any mistakes on the big night would be punished with a $50 to $100 fine.

The schedule was punishing, with the fourteen-piece James Brown Revue playing five performances every day for a week, leading up to the final show on October 24, which would be recorded for the album.

"We had opened on the 19th," recalled Brown later, "and were building up to recording on the 24th which was Amateur night. I wanted that wild Amateur Night crowd because I knew they'd do plenty of hollering."

Booking agent Jack Bart has recalled that, "It was freezing cold that day. Still, the ticket holders' lines stretched around two corners. It was incredible. Brown's people gave out free cups of coffee for everyone standing and waiting."

The show they got was impressive, headlined by Brown but also featuring Solomon Burke, Texan blues guitar maestro Freddie King, Sam Cooke proteges The Valentinos (featuring Bobby Womack and his brothers) and popular comedian Pigmeat Markham.

The Apollo stage was built of well-worn wooden planks and, from the crowd’s perspective, it resembled little more than a box twice as wide as it was tall.

Knowing how important the recording could be, Brown, Byrd and the rest of the company were anxious as showtime approached. King Records’ Vice President Hal Neely brought the live tapes backstage for them to hear between shows, enabling them to further refine the set as the day progressed.

In the words of Bobby Byrd, "There was tension, you know, we were nervous about recording and all. But the minute we hit the stage … magic!”

Emcee Fats Gonder primed the already hyped-up audience with a lengthy rant that began, "So now, ladies and gentlemen, it is Star Time. Are you ready for Star Time?!" Their screams and howls confirmed they were more than ready - they were gagging for it.

In his autobiography, Brown confirmed Byrd’s assessment. "As soon as I was into I’ll Go Crazy I knew it was one of those good times. That’s a hard feeling to describe - being on stage, performing and knowing that you’ve really got it that night."

Brown and his band, tightly drilled by trumpeter Lewis Hamlin, pounded out the hits, I’ll Go Crazy, Please Please Please, Night Train and the rest, with one outstanding highlight being a lengthy gospel-soaked Lost Someone, before climaxing the show with a nine-hit medley after which Brown quit the stage to the sound of a rampaging Night Train.

Although the show was a major triumph, the perfectionist in Brown was still not 100% satisfied. "Every now and then, the band made a mistake or The Flames were a half-tone off", he stated later.

Syd Nathan had been reluctant to allow the live recording from the start and, when he heard the completed tracks, he was still not keen to release the LP.

Nathan’s usual modus operandi was to release a few singles and see if any of them started to take off before risking an entire album. Thus, according to Brown, "He didn't like the way we went from one tune to another without stopping … I guess he was expecting exact copies of our earlier records, but with people politely applauding in between."

By fielding a string of petty objections, Nathan managed to delay release for almost eight months, and when it finally went on sale in May 1963, his conviction that it would not sell was evidenced by the fact that King Records’ initial pressing amounted to a mere 5000 copies.

In strictly business terms, Nathan’s approach was completely rational and understandable, but Live At The Apollo was anything but business as usual. The album was offering fans a visceral, overpoweringly emotional experience that defied conventional logic. The Billboard album charts at that time were dominated by MOR artists (Johnny Mathis), polite folkies (Peter, Paul and Mary), comedians (Allan Sherman) and soundtracks (West Side Story), bought by consumers who had probably never even heard of James Brown.

What Nathan did not understand was that times were changing. There were stirrings of racial integration, black consumers and white teenagers both had a little more folding money in their wallets, and with rock’n’roll languishing in the doldrums, there was a potentially huge, unsatisfied audience out there longing for music with considerably more spunk and guts than MOR pop could offer.

Imagine Nathan’s surprise then, when radio picked up on the album. "We played cuts from it during the day," explains disc jockey Rocky G of New York station WWRL. "But in the evening we had to play the whole thing, all the way through. People were always calling in, saying 'Play James Brown Live At The Apollo.'" And WWRL was not alone. The album caught fire right across America.

Spending a staggering 66 weeks on Billboard’s pop LP chart, it peaked at No2, held off the No1 slot ironically enough by an album which was its polar opposite - Andy Williams’ Days Of Wine And Roses.

Live At The Apollo earned James Brown the title of the Hardest-Working Man In Showbusiness and proved, in a wider context, that in-concert albums could be very good for business indeed, attracting a vast new audience to an already established artist.

Over the years, the status of Live At The Apollo has grown to such an extent that it is now routinely included in virtually any chart or listing of all-time essential albums. It is also cited as a prime influence on the output of later artists as diverse as The MC5, The Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson and Public Enemy.

Technically, Live At The Apollo is not a great-sounding record but it is an irreplaceable document of a truly great, innovative and soulful artist at the peak of his powers. What more do you want?

VINYL ICON - PRODUCTION NOTES

JAMES BROWN LIVE AT THE APOLLO

According to the original sleeve notes, this album was recorded "in Stereophonic Sound using AMPEX 350-2 tape machines. According to James Brown himself, it was done with portable Magnacorders - rare items at that time - rented from A-1 Sound in New York, to enhance the venue’s in-house PA system, mixer and mics.

Brown paid for the whole enterprise, so I’m inclined to trust his version of events, especially as those sleeve notes also listed the highly reputable Tom Nola of New York’s Nola Penthouse studio as engineer, but King Records’ Vice President Hal Neely claims to have engineered it, a fact which Brown confirmed in his autobiography, declaring, "He worked on the tape a long time and did a fantastic job of mixing it." Again, the Brown version makes sense, because although revered as a jazz producer, Nola did not enjoy rock’n’roll and usually farmed such work out.

What seems somewhat more reliable is that the recording used eight microphones, two of which were placed to capture audience response, but all of them fed into a 2-track recorder so 'mixing’ was a minimal process at best, probably limited to the engineer monitoring the recording on headphones, turning the audience mics down when the crowd was cheering, and up again during the bulk of the song.

One delightful anecdote involves a 70 year old old lady who was captured shouting, "Sing it, motherfucker, sing it", during a quiet interlude in Lost Someone. Neely, it seems, had strung up one of the audience mics on a wire between two side balconies, and it happened to be directly above the foul-mouthed old dear. Neely himself didn’t discern what she was shouting until he played the tape to the band backstage, and saw them collapsing in hysterical laughter. When they explained, Neely panicked and his first response was to find some way to exclude her voice from the tapes.

The band, however, thought it was very amusing, and prevailed on Neely to find a compromise of some sort. "He fixed all the cussing so it wasn’t right up front," explained Brown. "He figured it would be an underground thing for people who knew what the lady was screaming. He was right too."

When Neely’s carefully edited tapes were sent to chief engineer Chuck Seitz at King Records in Cincinnati, he detected another problem. "They had very, very little audience on them. I suggested we try to boost the audience up. I went out to Roselawn, to a dance they used to have out there, with a tape recorder. I knew the DJ, so he got them to applaud and cheer and I went back and inserted it where it was needed." As a result, most of the audience response on the original album comes from people who weren’t actually at the show.

This feature by Johnny Black first appeared in Hi Fi News - March 2017)