Fact #39124

When:

Short story:

Bob Dylan plays the last of fifteen nights as support to John Lee Hooker at Gerde's Folk City, Greenwich Village, New York City, USA.

Bob Dylan plays the last of fifteen nights as support to John Lee Hooker at Gerde's Folk City, Greenwich Village, New York City, USA.Full article:

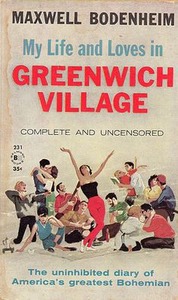

MEMORIES OF Greenwich Village IN THE EARLY 60s…

Jac Holzman (owner, Elektra Records) : The Village scene was a few square blocks of clubs, bars, red-sauce Italian restaurants that had been family-run for generations, and, of course, the coffee houses.

Izzy Young's Folklore Center, a few steps above MacDougal Street, was a storefront with a rough assemblage of records, sheet music, instruments, strings, capos, and the odd-lot necessities of the urban folk singer, displayed according to Izzy's cockeyed logic. Izzy was one of those unforgettable characters of whom everybody was fond but also wary. Maynard Solomon (co-founder of Vanguard Records] and I pretty much kept him in business by granting him ridiculously generous terms of payment. "Izzy," we begged, "if you sell it, please pay for it." The rent would come due and Izzy would be just a bit short of cash, and you know who got paid first. But Izzy knew all of folkdom and the Center served as Musician's Central Station.

Just a few doors south was a heavy hangout bar, the Kettle of Fish. The Kettle was sawdusty, dimly lit, comfortable, and much beloved for its turmoil. It did not have live entertainment, so it was uncontested terrain, and it became a community watering hole. I remember one night when Dave Van Ronk, John Sebastian, Richard Farina, Tom Rush, Albert Grossman and Bob Dylan all showed up. At the Kettle you could always find out what was or might be happening, and to be on the safe side you checked in, like knocking on wood. The Kettle was the hub, and from there you fanned out and sampled the action. The Gaslight Cafe was directly downstairs, it was just a short walk to Gerde's Folk City, The Village Gate, the Bitter End, and on and on.

Paul Siebel (singer-songwriter) : I lived in a walkup at 139 Thompson Street, just below Houston, right next to the Catholic Church; I remember those church bells going off. I was from Buffalo, which was a closed scene. I thought I'd just better get out of there with my guitar. I headed for New York. For a while I worked in a baby carriage factory in Brooklyn, but I gravitated to the Village. I was making forty-some dollars at the baby carriage factory, and I would save my money and go see a double bill in the Village, which would be, like, Ramblin' Jack Elliott and Mississippi John Hurt, and that would be a magical night.

I would be wearing Levi's, a lot of denim. I couldn't afford good boots. Definitely a wide belt with the Levi's, though. Fancy buckles were a problem because they scratched the back of your guitar. I have a picture of myself wearing a belt with the buckle on the side, around my hips, so it wouldn't scratch. I think Jerry Jeff Walker actually gouged a hole in the back of his guitar because of heavy buckles. Another thing that was worn-I didn't, I'm proud to say, and I won't mention any names-but guys would wear a little leather pouch with a drawstring hanging from the belt, and they would keep finger picks and guitar picks and sometimes dope paraphernalia, a little pipe and some Zig-Zag rolling papers.

I was a folkie, but there was a lot of overlap. When a Dylan album came out, or a Beatles album, the kids would line up outside the record stores. If they heard that it was coming out on Thursday, they'd start on Wednesday night, and there'd be thousands of them. Reporters would be down interviewing them.

Being in the Village was kind of the epicenter of all that. In fact, it would get so crowded on the streets at night that the police would block off Bleecker Street and West 3rd and MacDougal and not let cars drive through.

There was dope on the streets. You could be pretty casual about it. I can remember the cop on the beat, Jack, and the other good-looking one, looked like a movie star, asking us, "Please smoke a little farther down the street" - if the captain went by they'd get in trouble. The stuff was just all over. In everybody's apartment. All the girls used it, just about everyone I knew, they would have the fixings in some wooden bowl sitting on the coffee table, with posters on the wall. In fact the mothers of MacDougal Street were protesting, "Do away with the coffee houses," because it was corrupting youth. Well, it was. You bet. Why else would anyone be there? When you're in your early twenties, it was nice. It wasn't crazy dangerous like today, between the dope and the violence. Then it was just pretty much kids. It was us, and what we'd snobbishly refer to as the uptown crowd, people slumming or just trying to hang out in the Village, some people who were closet guitar players: "I know a few chords, listen to this," and they'd go into 'They Call The Wind Maria' or something.

Bob Gibson (New York folk musician) : The guys who originally got involved in running the coffee houses were not altogether savory. One of these reasons they opened coffee houses was to avoid the police department cabaret permit ban on those who had been convicted of felonies or drug arrests or things like that. They did not have to have a police permit to sell coffee, tea or mulled cider.

Paul Siebel : You could go down the street and hear singing several houses away because there was a rickety kind of amplification. They had guys who would stand outside, usually quite colourful characters, some of them had done some time, and they were called drags, because they dragged the streets to get people to come in. They would usually dress quite spectacularly. They were the first guys I remember wearing extremely long hair, shoulder length or longer, earrings, tattoos, that sort of thing.

These places were called basket houses. The performers weren't paid. You would do a set and do a basket pitch: "This is my last song, and at the end of the song we're gonna pass a basket. I would appreciate anything from a joint to the colour green, I like the colour green."

I was hired at the Four Winds by Charlie Chin, a Chinese-American guy. I quit my job at the baby carriage factory the next day. I worked at the Four Winds for more than a year, five or six sets a night. Of course you fought for the spot, and to hold it. You didn't want to lose it, but on the other hand you wanted other good players to share the night, to help pull people into the place. I worked through the lean times, which was the winter when it snowed and blowed, and sometimes you and your girlfriend and the other performers would be the only ones in the club, and you'd maybe only get two or three dollars in the basket, maybe make five dollars a night. But other times we would do very well. Sometimes the girls would make a hundred in a night, and I can remember making sixty and seventy, and my God, that's all we were paying a month for rent.

Richie Havens, I remember seeing him in a place called the Zig-Zag. I also worked with Peter Tork-he played a long-neck banjo and sang kind of silly things, like this thing called 'Elmo,' which was an alligator that went down the drainpipe. He said he had to get out of New York, nothing was happening for him, he was gonna go to California, and he did, and he turned into a Monkee.

Michael Ochs (rock archivist) : Everybody was in this ten-block radius. It was dirt cheap. It didn't cost anything. Almost any kid could afford it. Most places there was no cover charge, maybe a two-drink minimum.

The Pete Seegers, the Oscar Brands, the Ed McCurdys, would still be playing, and it would usually be a mixture. Ed McCurdy would be the headliner and Patrick Sky would open for him, or Oscar Brand would be the headliner and they'd have Patrick Sky opening for him.

The old Night Owl Café, everybody used to hang out there a lot. It used to be Tim Hardin singing, and behind him would be Freddie Neil playing guitar, Peter Childs second guitar, John Sebastian playing harmonica; he wasn't a singer yet. They would go from a Bo Diddley tune to a Freddie Neil tune, back to some classic rock and roll. I saw Hardin play four hours straight one night and he didn't open his eyes once. Talk about heroin…

Jac Holzman (owner, Elektra Records) : Elektra signed many singer-songwriters, some of whom were kinder and gentler, others more strenuous and political. It was the nature of the times. The world was in the Village and the Village was the world.

Tweet this Fact

Jac Holzman (owner, Elektra Records) : The Village scene was a few square blocks of clubs, bars, red-sauce Italian restaurants that had been family-run for generations, and, of course, the coffee houses.

Izzy Young's Folklore Center, a few steps above MacDougal Street, was a storefront with a rough assemblage of records, sheet music, instruments, strings, capos, and the odd-lot necessities of the urban folk singer, displayed according to Izzy's cockeyed logic. Izzy was one of those unforgettable characters of whom everybody was fond but also wary. Maynard Solomon (co-founder of Vanguard Records] and I pretty much kept him in business by granting him ridiculously generous terms of payment. "Izzy," we begged, "if you sell it, please pay for it." The rent would come due and Izzy would be just a bit short of cash, and you know who got paid first. But Izzy knew all of folkdom and the Center served as Musician's Central Station.

Just a few doors south was a heavy hangout bar, the Kettle of Fish. The Kettle was sawdusty, dimly lit, comfortable, and much beloved for its turmoil. It did not have live entertainment, so it was uncontested terrain, and it became a community watering hole. I remember one night when Dave Van Ronk, John Sebastian, Richard Farina, Tom Rush, Albert Grossman and Bob Dylan all showed up. At the Kettle you could always find out what was or might be happening, and to be on the safe side you checked in, like knocking on wood. The Kettle was the hub, and from there you fanned out and sampled the action. The Gaslight Cafe was directly downstairs, it was just a short walk to Gerde's Folk City, The Village Gate, the Bitter End, and on and on.

Paul Siebel (singer-songwriter) : I lived in a walkup at 139 Thompson Street, just below Houston, right next to the Catholic Church; I remember those church bells going off. I was from Buffalo, which was a closed scene. I thought I'd just better get out of there with my guitar. I headed for New York. For a while I worked in a baby carriage factory in Brooklyn, but I gravitated to the Village. I was making forty-some dollars at the baby carriage factory, and I would save my money and go see a double bill in the Village, which would be, like, Ramblin' Jack Elliott and Mississippi John Hurt, and that would be a magical night.

I would be wearing Levi's, a lot of denim. I couldn't afford good boots. Definitely a wide belt with the Levi's, though. Fancy buckles were a problem because they scratched the back of your guitar. I have a picture of myself wearing a belt with the buckle on the side, around my hips, so it wouldn't scratch. I think Jerry Jeff Walker actually gouged a hole in the back of his guitar because of heavy buckles. Another thing that was worn-I didn't, I'm proud to say, and I won't mention any names-but guys would wear a little leather pouch with a drawstring hanging from the belt, and they would keep finger picks and guitar picks and sometimes dope paraphernalia, a little pipe and some Zig-Zag rolling papers.

I was a folkie, but there was a lot of overlap. When a Dylan album came out, or a Beatles album, the kids would line up outside the record stores. If they heard that it was coming out on Thursday, they'd start on Wednesday night, and there'd be thousands of them. Reporters would be down interviewing them.

Being in the Village was kind of the epicenter of all that. In fact, it would get so crowded on the streets at night that the police would block off Bleecker Street and West 3rd and MacDougal and not let cars drive through.

There was dope on the streets. You could be pretty casual about it. I can remember the cop on the beat, Jack, and the other good-looking one, looked like a movie star, asking us, "Please smoke a little farther down the street" - if the captain went by they'd get in trouble. The stuff was just all over. In everybody's apartment. All the girls used it, just about everyone I knew, they would have the fixings in some wooden bowl sitting on the coffee table, with posters on the wall. In fact the mothers of MacDougal Street were protesting, "Do away with the coffee houses," because it was corrupting youth. Well, it was. You bet. Why else would anyone be there? When you're in your early twenties, it was nice. It wasn't crazy dangerous like today, between the dope and the violence. Then it was just pretty much kids. It was us, and what we'd snobbishly refer to as the uptown crowd, people slumming or just trying to hang out in the Village, some people who were closet guitar players: "I know a few chords, listen to this," and they'd go into 'They Call The Wind Maria' or something.

Bob Gibson (New York folk musician) : The guys who originally got involved in running the coffee houses were not altogether savory. One of these reasons they opened coffee houses was to avoid the police department cabaret permit ban on those who had been convicted of felonies or drug arrests or things like that. They did not have to have a police permit to sell coffee, tea or mulled cider.

Paul Siebel : You could go down the street and hear singing several houses away because there was a rickety kind of amplification. They had guys who would stand outside, usually quite colourful characters, some of them had done some time, and they were called drags, because they dragged the streets to get people to come in. They would usually dress quite spectacularly. They were the first guys I remember wearing extremely long hair, shoulder length or longer, earrings, tattoos, that sort of thing.

These places were called basket houses. The performers weren't paid. You would do a set and do a basket pitch: "This is my last song, and at the end of the song we're gonna pass a basket. I would appreciate anything from a joint to the colour green, I like the colour green."

I was hired at the Four Winds by Charlie Chin, a Chinese-American guy. I quit my job at the baby carriage factory the next day. I worked at the Four Winds for more than a year, five or six sets a night. Of course you fought for the spot, and to hold it. You didn't want to lose it, but on the other hand you wanted other good players to share the night, to help pull people into the place. I worked through the lean times, which was the winter when it snowed and blowed, and sometimes you and your girlfriend and the other performers would be the only ones in the club, and you'd maybe only get two or three dollars in the basket, maybe make five dollars a night. But other times we would do very well. Sometimes the girls would make a hundred in a night, and I can remember making sixty and seventy, and my God, that's all we were paying a month for rent.

Richie Havens, I remember seeing him in a place called the Zig-Zag. I also worked with Peter Tork-he played a long-neck banjo and sang kind of silly things, like this thing called 'Elmo,' which was an alligator that went down the drainpipe. He said he had to get out of New York, nothing was happening for him, he was gonna go to California, and he did, and he turned into a Monkee.

Michael Ochs (rock archivist) : Everybody was in this ten-block radius. It was dirt cheap. It didn't cost anything. Almost any kid could afford it. Most places there was no cover charge, maybe a two-drink minimum.

The Pete Seegers, the Oscar Brands, the Ed McCurdys, would still be playing, and it would usually be a mixture. Ed McCurdy would be the headliner and Patrick Sky would open for him, or Oscar Brand would be the headliner and they'd have Patrick Sky opening for him.

The old Night Owl Café, everybody used to hang out there a lot. It used to be Tim Hardin singing, and behind him would be Freddie Neil playing guitar, Peter Childs second guitar, John Sebastian playing harmonica; he wasn't a singer yet. They would go from a Bo Diddley tune to a Freddie Neil tune, back to some classic rock and roll. I saw Hardin play four hours straight one night and he didn't open his eyes once. Talk about heroin…

Jac Holzman (owner, Elektra Records) : Elektra signed many singer-songwriters, some of whom were kinder and gentler, others more strenuous and political. It was the nature of the times. The world was in the Village and the Village was the world.