Fact #34637

When:

Short story:

Eric Clapton, Duane Allman and their band Derek And The Dominos record Bell Bottom Blues, I Looked Away and Have You Ever Loved A Woman, for the album Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs at Criteria Studios, Miami, Florida, USA.

Eric Clapton, Duane Allman and their band Derek And The Dominos record Bell Bottom Blues, I Looked Away and Have You Ever Loved A Woman, for the album Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs at Criteria Studios, Miami, Florida, USA.Full article:

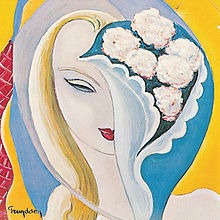

Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs

- Derek And The Dominos

This feature by Johnny Black first appeared in Hi Fi News

“We were staying in this hotel on the beach,” remembers Eric Clapton, “and whatever drug you wanted, you could get it at the newsstand. The girl would just take your orders.”

This was the state of affairs when Clapton and his newly-formed band, Derek And The Dominos, pitched up Criteria Studios in Miami, Florida, in late August 1970, to begin work on the tracks that would, during a ten-day recording frenzy, form the basis of the Layla album.

Clapton's career had been in disarray ever since the disintegration of his supergroup Cream in late 1968. His next outing had been another inherently unstable supergroup, Blind Faith with Steve Winwood, which barely lasted a year before Clapton took up with the erratic Delaney And Bonnie for a couple of months. In the spring of 1970, with their help, he rattled off his first solo album, Eric Clapton, in Los Angeles, but then took over their excellent backing group (Carl Radle on bass, Bobby Whitlock on keyboards and Jim Gordon on drums). He named this aggregation Derek And The Dominos and, after a scattershot tour of UK clubs, headed for Miami to make an album.

Clapton had been suffering from multiple-drug dependencies for several years by this point, and his new band-mates were just as bad. Inevitably, cocooned in Criteria Studios, drugs took priority over music from day one. "We didn't have little bits of anything," explained Whitlock some years later. "We had these big bags laying out everywhere. I'm almost ashamed to tell it, but it's the truth. It was scary, what we were doing, but we were just young and dumb and didn't know. Cocaine and heroin, that's all, and Johnny Walker."

Understandably, when music critic Robert Palmer showed up to interview Clapton, he found, "everyone was just spread out on the carpet, nodded out."

Nor did it help that, apart from the album's title track (about Clapton's lust for George Harrison's fashion-model wife Patti Boyd) and a handful of songs Clapton and Whitlock had started writing at Clapton's Italianate villa, Hurtwood Edge, in Surrey, they really didn't have much idea of what they were going to record. In the words of Tom Dowd, "They were not prepared. They had lots of ideas, but nothing solid."

"The first three days we went in there and we struggled and we put two of the songs on there," admitted Clapton subsequently.

They desperately needed a boot up their collective backsides and, luckily, Tom Dowd had a firecracker of an idea about how he might help achieve that.

On August 26, the band spent some time working on the song Have You Ever Loved A Woman?, but the main event of the day came when Dowd shook them out of their stupor by taking Clapton to see The Allman Brothers Band playing at The Convention Center in nearby Miami Beach.

Clapton had been a fan of Duane Allman's playing ever since hearing his spirited licks on Wilson Pickett's 1969 version of Hey Jude, while Allman had admired Clapton for as long as he could remember. Allman later recalled that Clapton, “greeted me like an old friend” and, as Dowd had no doubt hoped, their musical rapport when they got together in Criteria was instantaneous.

According to Clapton, "He showed up and that was just it. It just took off. He was the catalyst for the whole thing."

The bulk of the Allmans band was in Criteria on August 27, jamming on songs including It Hurts Me Too and Tell The Truth, but by the next day, only Duane was still there and Clapton was determined not to let him go. "I kept thinking up ways to keep him in the room. 'We could do this … do you know this one?' … I knew that sooner or later he was going back to The Allmans but I wanted to steal him."

As Dowd remembers it, the atmosphere in the studio was super-charged. "They were trading licks. They were swapping guitars. They were talking shop and information and having a ball - no holds barred, just admiration for each other's technique and facility. There was no control. We turned the tapes on and they went on for 15 to 18 hours like that. You just kept the machines rolling. I went through two or three sets of engineers. It was a wonderful experience." Dowd also insists that, despite their undeniably massive drug consumption, once they set to work they were focussed and functional.

Working at a furious pace, they recorded The Keys To The Highway on the 30th, re-visited Have You Ever loved A Woman? on the 31st, along with Nobody Knows You When You're Down And Out, and Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?, and did Keep On Growing the next day.

Vocals too were virtually live. Dowd has memories of them sitting, "Indian style on the floor in a circle with two omni-directional mikes in the centre and they sang and played the whole thing live."

Many of these tracks ended up on vinyl as first or second takes, but the album's centre-piece, Layla, required rather more care and attention.

Clapton had started writing it in Hurtwood Edge as a basic blues shuffle, based on an ancient Persian love story, Layla and Majnun, which he felt had similarities to the story of his forbidden love for Patti Boyd. "I remember writing the words and the changes," he told journalist Steve Turner, "but the things that make the song what it is - like the riff and the end part - were done in the studio."

Allman had touring commitments with his own band which took him away in early September but he was back at Criteria on the 9th, to get to grips with Clapton's half-finished Layla. His major contribution was the powerfully surging opening lick that galvanised it into a world-beater.

It wasn’t, however, original. The lick was borrowed from blues great Albert King's 1967 track As The Years Go Passing By. “Duane heard that,” acknowledges Clapton, “and he just speeded it up … no-one would notice that the riff is exactly the same, except slow blues.”

It seemed the sessions were now over but, to Dowd's surprise, they returned to Criteria on October 1. Clapton had been inspired by hearing drummer Jim Gordon fooling around with a piano lick that his former band, Delaney & Bonnie, had frequently used for jamming. Clapton decided it would make an ideal coda for Layla but Gordon was not an accomplished pianist, so Dominos keyboard player Bobby Whitlock was drafted in to "give it some feel. So Jim recorded it, I recorded it, and Tom Dowd mixed them together. It's two pianos."

With the double-album finally complete, Tom Dowd was a happy man. "When I finished doing the Layla album, I walked out of the studio and said, 'That's the best goddam record I've made in ten years.'"

At first, the public did not agree. Both the album and its title track flopped on release, but the Atlantic Records' marketing team refused to let it die. On re-issue in 1972, Layla went Top 10, and by 1975 it was, by popular demand, the opener for every Clapton concert. It now boasts an unassailable position as Clapton’s most enduring anthem, having returned to the UK Top 5 in 1982, and to the Billboard Top 20 in 1992 in its unplugged version

From one perspective, Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs is a saga of creativity and hard graft overcoming the drug-addled stupor of Derek And The Dominos to deliver a redemptive and magnificent album but, inevitably, there was a price to be paid for their descent into chemical oblivion, which carried on after recording was finished.

Duane Allman died in 1971 when he rode his Harley into the back of a truck. Carl Radle died in 1980 from a heroin-related illness. Jim Gordon, having become schizophrenic, stabbed his mother to death in 1983, ending up in a mental hospital. Only Clapton and Whitlock have survived, but both now acknowledge that they will bear the scars from those days forever.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PRODUCTION NOTES

The sound of Layla And Other Assorted Love Stories is, in essence, the sound of the legendary MCI console at Criteria Recording Studios in North Miami, Florida, enhanced by the genius of veteran producer Tom Dowd.

The much-fabled Mr Dowd started as an audio engineer in 1949 and, after joining Atlantic Records, initiated their switch from recording on acetate discs to recording on tape, introduced them to stereo in 1952, and went on to build their recording console and design their eight-track studio on Broadway in New York City. In short, the sound of Atlantic Records, was the sound of Tom Dowd, whose productions for The Modern Jazz Quartet, Ray Charles, The Coasters, John Coltrane, Aretha Franklin and others made him a multiple Grammy winner.

Clapton first worked with Dowd on Cream's Disraeli Gears in 1967, and considered him the bees knees. When the time came to make an album with The Dominos, Dowd was in Criteria working on The Allman Brothers' Idlewild South, so it made sense to go there.

Criteria had started in 1958 but it was the MCI console designed and installed in 1968 by audio pioneer Jeep Harned that thrust it into the forefront.

In layman's terms, its characteristic sound was "big, fat and warm", but for those who need to know more, it was the first console to employ ultra-sensitive controls where the touch of the operator's skin completed the circuit. Every contacts was 14 karat gold and every control was illuminated by a different colour. Originally a sixteen-channel desk, it was later upgraded to 24.

Dowd knew he could rely on the MCI to capture every sonic nuance, but once Allman arrived and the creative juices started to flow, he also knew he would have to use it to the max. Ideas were coming so thick and fast that he found himself, "recording everything the entire time they were in the studio". The end, as any Clapton fan will attest, more than justified the means.

Tweet this Fact

This feature by Johnny Black first appeared in Hi Fi News

“We were staying in this hotel on the beach,” remembers Eric Clapton, “and whatever drug you wanted, you could get it at the newsstand. The girl would just take your orders.”

This was the state of affairs when Clapton and his newly-formed band, Derek And The Dominos, pitched up Criteria Studios in Miami, Florida, in late August 1970, to begin work on the tracks that would, during a ten-day recording frenzy, form the basis of the Layla album.

Clapton's career had been in disarray ever since the disintegration of his supergroup Cream in late 1968. His next outing had been another inherently unstable supergroup, Blind Faith with Steve Winwood, which barely lasted a year before Clapton took up with the erratic Delaney And Bonnie for a couple of months. In the spring of 1970, with their help, he rattled off his first solo album, Eric Clapton, in Los Angeles, but then took over their excellent backing group (Carl Radle on bass, Bobby Whitlock on keyboards and Jim Gordon on drums). He named this aggregation Derek And The Dominos and, after a scattershot tour of UK clubs, headed for Miami to make an album.

Clapton had been suffering from multiple-drug dependencies for several years by this point, and his new band-mates were just as bad. Inevitably, cocooned in Criteria Studios, drugs took priority over music from day one. "We didn't have little bits of anything," explained Whitlock some years later. "We had these big bags laying out everywhere. I'm almost ashamed to tell it, but it's the truth. It was scary, what we were doing, but we were just young and dumb and didn't know. Cocaine and heroin, that's all, and Johnny Walker."

Understandably, when music critic Robert Palmer showed up to interview Clapton, he found, "everyone was just spread out on the carpet, nodded out."

Nor did it help that, apart from the album's title track (about Clapton's lust for George Harrison's fashion-model wife Patti Boyd) and a handful of songs Clapton and Whitlock had started writing at Clapton's Italianate villa, Hurtwood Edge, in Surrey, they really didn't have much idea of what they were going to record. In the words of Tom Dowd, "They were not prepared. They had lots of ideas, but nothing solid."

"The first three days we went in there and we struggled and we put two of the songs on there," admitted Clapton subsequently.

They desperately needed a boot up their collective backsides and, luckily, Tom Dowd had a firecracker of an idea about how he might help achieve that.

On August 26, the band spent some time working on the song Have You Ever Loved A Woman?, but the main event of the day came when Dowd shook them out of their stupor by taking Clapton to see The Allman Brothers Band playing at The Convention Center in nearby Miami Beach.

Clapton had been a fan of Duane Allman's playing ever since hearing his spirited licks on Wilson Pickett's 1969 version of Hey Jude, while Allman had admired Clapton for as long as he could remember. Allman later recalled that Clapton, “greeted me like an old friend” and, as Dowd had no doubt hoped, their musical rapport when they got together in Criteria was instantaneous.

According to Clapton, "He showed up and that was just it. It just took off. He was the catalyst for the whole thing."

The bulk of the Allmans band was in Criteria on August 27, jamming on songs including It Hurts Me Too and Tell The Truth, but by the next day, only Duane was still there and Clapton was determined not to let him go. "I kept thinking up ways to keep him in the room. 'We could do this … do you know this one?' … I knew that sooner or later he was going back to The Allmans but I wanted to steal him."

As Dowd remembers it, the atmosphere in the studio was super-charged. "They were trading licks. They were swapping guitars. They were talking shop and information and having a ball - no holds barred, just admiration for each other's technique and facility. There was no control. We turned the tapes on and they went on for 15 to 18 hours like that. You just kept the machines rolling. I went through two or three sets of engineers. It was a wonderful experience." Dowd also insists that, despite their undeniably massive drug consumption, once they set to work they were focussed and functional.

Working at a furious pace, they recorded The Keys To The Highway on the 30th, re-visited Have You Ever loved A Woman? on the 31st, along with Nobody Knows You When You're Down And Out, and Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad?, and did Keep On Growing the next day.

Vocals too were virtually live. Dowd has memories of them sitting, "Indian style on the floor in a circle with two omni-directional mikes in the centre and they sang and played the whole thing live."

Many of these tracks ended up on vinyl as first or second takes, but the album's centre-piece, Layla, required rather more care and attention.

Clapton had started writing it in Hurtwood Edge as a basic blues shuffle, based on an ancient Persian love story, Layla and Majnun, which he felt had similarities to the story of his forbidden love for Patti Boyd. "I remember writing the words and the changes," he told journalist Steve Turner, "but the things that make the song what it is - like the riff and the end part - were done in the studio."

Allman had touring commitments with his own band which took him away in early September but he was back at Criteria on the 9th, to get to grips with Clapton's half-finished Layla. His major contribution was the powerfully surging opening lick that galvanised it into a world-beater.

It wasn’t, however, original. The lick was borrowed from blues great Albert King's 1967 track As The Years Go Passing By. “Duane heard that,” acknowledges Clapton, “and he just speeded it up … no-one would notice that the riff is exactly the same, except slow blues.”

It seemed the sessions were now over but, to Dowd's surprise, they returned to Criteria on October 1. Clapton had been inspired by hearing drummer Jim Gordon fooling around with a piano lick that his former band, Delaney & Bonnie, had frequently used for jamming. Clapton decided it would make an ideal coda for Layla but Gordon was not an accomplished pianist, so Dominos keyboard player Bobby Whitlock was drafted in to "give it some feel. So Jim recorded it, I recorded it, and Tom Dowd mixed them together. It's two pianos."

With the double-album finally complete, Tom Dowd was a happy man. "When I finished doing the Layla album, I walked out of the studio and said, 'That's the best goddam record I've made in ten years.'"

At first, the public did not agree. Both the album and its title track flopped on release, but the Atlantic Records' marketing team refused to let it die. On re-issue in 1972, Layla went Top 10, and by 1975 it was, by popular demand, the opener for every Clapton concert. It now boasts an unassailable position as Clapton’s most enduring anthem, having returned to the UK Top 5 in 1982, and to the Billboard Top 20 in 1992 in its unplugged version

From one perspective, Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs is a saga of creativity and hard graft overcoming the drug-addled stupor of Derek And The Dominos to deliver a redemptive and magnificent album but, inevitably, there was a price to be paid for their descent into chemical oblivion, which carried on after recording was finished.

Duane Allman died in 1971 when he rode his Harley into the back of a truck. Carl Radle died in 1980 from a heroin-related illness. Jim Gordon, having become schizophrenic, stabbed his mother to death in 1983, ending up in a mental hospital. Only Clapton and Whitlock have survived, but both now acknowledge that they will bear the scars from those days forever.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PRODUCTION NOTES

The sound of Layla And Other Assorted Love Stories is, in essence, the sound of the legendary MCI console at Criteria Recording Studios in North Miami, Florida, enhanced by the genius of veteran producer Tom Dowd.

The much-fabled Mr Dowd started as an audio engineer in 1949 and, after joining Atlantic Records, initiated their switch from recording on acetate discs to recording on tape, introduced them to stereo in 1952, and went on to build their recording console and design their eight-track studio on Broadway in New York City. In short, the sound of Atlantic Records, was the sound of Tom Dowd, whose productions for The Modern Jazz Quartet, Ray Charles, The Coasters, John Coltrane, Aretha Franklin and others made him a multiple Grammy winner.

Clapton first worked with Dowd on Cream's Disraeli Gears in 1967, and considered him the bees knees. When the time came to make an album with The Dominos, Dowd was in Criteria working on The Allman Brothers' Idlewild South, so it made sense to go there.

Criteria had started in 1958 but it was the MCI console designed and installed in 1968 by audio pioneer Jeep Harned that thrust it into the forefront.

In layman's terms, its characteristic sound was "big, fat and warm", but for those who need to know more, it was the first console to employ ultra-sensitive controls where the touch of the operator's skin completed the circuit. Every contacts was 14 karat gold and every control was illuminated by a different colour. Originally a sixteen-channel desk, it was later upgraded to 24.

Dowd knew he could rely on the MCI to capture every sonic nuance, but once Allman arrived and the creative juices started to flow, he also knew he would have to use it to the max. Ideas were coming so thick and fast that he found himself, "recording everything the entire time they were in the studio". The end, as any Clapton fan will attest, more than justified the means.