Fact #154451

When:

Short story:

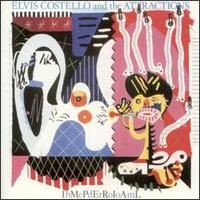

Elvis Costello And The Attractions release a new LP, Imperial Bedroom, on F-Beat Records in the UK, Europe.

Elvis Costello And The Attractions release a new LP, Imperial Bedroom, on F-Beat Records in the UK, Europe.Full article:

VINYL ICON by Johnny Black

ELVIS COSTELLO - IMPERIAL BEDROOM

Costello’s seventh, and arguably greatest, album arrived in 1982 at a point when rock’s former 'angry young man' was taking a fresh look at everything he had achieved so far.

With his first flush of late 70s’ hit singles success having run dry, he’d started to re-evaluate virtually every aspect of his life. As he put it himself, "I had enough sense to say, 'If you don’t look after yourself a bit more, you’re going to be dead. Stop taking drugs, stop drinking so much and behave a bit. You really are turning into a bore about being an artist. It’s not important to anybody and, if you carry on like this, you’re not going to do anybody any good."

After years of working with Nick Lowe as his producer, Costello had gone to Nashville in 1981 and recorded the country-influenced Almost Blue with veteran producer Billy Sherrill. As well as being a dramatic stylistic departure for Costello, that experience enabled him to step outside his normal boundaries.

For one thing, he put down his usual compositional tool, the guitar, and moved to a keyboard. "I had a piano and I sat around and I wrote almost all of Imperial Bedroom on the piano … which I can’t play," he admitted. "My father taught me a little bit when I was seventeen."

Well aware of his pianistic shortcomings, he would show what he had done to Attractions keyboardist Steve Nieve who would then, "interpret them, voice them better ways."

This process was underway during the recording of Almost Blue, so come the winter of 1981, when demos for Imperial Bedroom were recorded with house engineer Howard Massey at Pathway Studios in London, most of the songs were already written.

Costello had also become increasingly aware that his aggressive vocal style had become something of a limiting factor. "I didn’t change the keys," he explained, "but I changed the register on about half the vocals on the record. After we recorded the backing tracks, three or four of the songs ended up being an octave lower than we’d rehearsed them."

Another realisation was that, "I was sacrificing the power of certain songs to this mad pursuit of tempo. Everything had to be delivered forcefully. I don’t know whether it was just a natural process or, literally, cumulative exhaustion of what were very intense years. Man Out of Time is the one time I said, ‘No, stop. Let’s play this at the right tempo.’"

The sessions for Imperial Bedroom took place at AIR Studios in London, over a three-month period, under the watchful eye of producer Geoff Emerick, who had earned his spurs as an engineer on several Beatles’ albums.

"We were trying to capture Elvis's spontaneity, because he's a first-take kind of guy," Emerick has recalled. "We wanted to get back to basics. Elvis is very fast. When we did the first session, there was an onslaught of something like eighteen songs, which we cut in fast takes. It took me quite by surprise. From then on, it was a matter of thinking which ones should we record."

Although a lot of tracks were recorded very quickly, Costello was far from satisfied with what had been achieved. "We recorded all the backing tracks and then the band went home and I stayed in the studio on my own for several weeks recording the vocals. I changed two or three of the songs. I wrote a new song on top of what they thought to be the song, and overlaid a new melody and lyric on their original changes."

Where once Costello had relished the minimalist thrills of working strictly in a small band format, he was now forging ahead into other areas, and found Steve Nieve invaluable as an arranger who could realise his grander visions. "Steve didn't want the standard orchestration - first and second violins, cellos and so on," remembered Emerick. "On Town Cryer, and some of the other songs, we used, I think, eighteen violas, which was really unique."

Costello has admitted that, carried away by the excitement of his new direction, "We hired an orchestra for Steve to arrange for. We hired a harpsichord; we had no idea what to do with it. We bought an accordion, and none of us could play it, so it took three of us to wrestle it into submission."

The accordion is heard on The Long Honeymoon, and Elvis clarified the wrestling technique in the sleeve notes to the 2002 album re-issue, explaining how, "Laying the instrument on the table, Steve played the keyboard, while one of us worked the bellows, and a third party held the beast in place."

Not only was Costello exploring new levels of sophistication, he was actively abandoning any attempt at making commercially-marketable music. "We made a record that couldn't possibly get on the radio, and actually relished that," he later revealed. "It was a sort of like, 'Fuck you, we'll just do this now.' Not to the audience, but to the record companies and radio that don't really want you around."

In 1983, Elvis told Paul Rambali of The Face that, "I was making all the production decisions. It's very hard when you're judging your own work. Some of the things that I held out for – when everyone said I was wrong – six months later I found I was wrong! There's that song Kid About It, which I insisted on singing in an entirely unsuitable octave. I was trying to get away from having one vocal feel throughout, the sort of 'one-man-tortured-by-his-art' thing, so I went completely the other way and used overlapping vocals and conflicting styles to suggest there was more than one attitude going on inside the songs. Some of it worked perfectly well, a rather more theatrical way of singing, if you like, because I wanted to get away from that sort of soul singing and do something cooler, in the old-fashioned sense."

Three songs from Imperial Bedroom - Beyond Belief, Man Out of Time and Almost Blue - have remained staples of Costello’s live shows, so it’s worth considering each of those in some detail.

Speaking of the spacious widescreen opening track, Beyond Belief, Costello has explained, "We were moving into the period of big open-spaced music - U2, Echo And The Bunnymen - and suddenly our tight little songs were out of step. This is a ranting kind of song. I was consciously writing words that didn't make sense - to make a blurred picture, because I was living a blurred life."

As the term 'blurred life' suggests, the early 80s were an emotionally troubled time for Costello, not least because his first marriage was disintegrating. As a result many of the album’s lyrics, although rich in clever wordplay, are virtually impenetrable. "Man Out Of Time was the product of a troubling dialogue with myself that continued through my more regretful moments," he has said. "I recall looking at my reflection in the frozen window of a Scandinavian tour bus without any idea who the hell I was supposed to be."

Although he could hide his meanings from his audience in obscure lyrics, the other band members could clearly see what was tearing him up. "Bruce Thomas of The Attractions thought I was being too obsessed with domestic strife. But it wasn’t that I was obsessed with it, it just made the strongest songs. It’s not because of the subject; the saddest songs made the strongest songs. I always write better sad songs."

The third of this trio, Almost Blue, has become Costello’s most-covered song, and was, he has revealed, "written in imitation of the (Lew Brown/Ray Henderson 1931 jazz standard) song The Thrill Is Gone. I had become obsessed with the Chet Baker recording of that tune, firstly the trumpet instrumental and, later, the vocal take. It is probably the most faithful likeness to the model of any of my songs of this time." Costello was understandably delighted when, some years later, he learned that Baker had been including Almost Blue in his live shows.

In a feature of this length, it’s impossible to detail every one of the fifteen tracks on Imperial Bedroom, but Costello’s comments about The Loved Ones are worth repeating for the light they shed on the complexity of his thinking. "That is the hardest song to get over," he said. "Considering it’s got such a light pop tune, it’s like saying, 'Fuck posterity; it’s better to live.' It’s the opposite of Rust Never Sleeps. It’s about, 'Fuck being a junkie and dying in some phony romantic way like Brendan Behan or Dylan Thomas'. Somebody in your family’s got to bury you, you know? That’s a complicated idea to put in a pop song. I didn’t want to write a story around it - I wanted to just throw all of those ideas into a song. Around a good pop hook."

Imperial Bedroom divided reviewers in 1982, but although its reputation has only grown with time, Costello has always been the album’s harshest critic. "In retrospect, I feel some of the songs are just not well written enough," he said in a 1988 interview with Rolling Stone. "Some of them were attempts to create a little mystery room the listener could go into. And in some cases, the subject matter is maybe too large for the song's own good."

Nevertheless, he must harbour considerable affection for it, because he named his most recent tour Imperial Bedroom and Other Chambers. Typically, though, there was no attempt to faithfully reproduce his 1982 classic. "We’re not playing it the way it was originally written or heard," says Costello. "We're going back and listening and saying, 'What's good on those recordings? What isn't so good? What can we do better?"

In an era when most so-called heritage artists are perfectly content to spoon feed their devoted audiences with whatever they find most palatable, we can only be grateful that Elvis Costello remains as unpredictably uncompromising as he has been from the start.

IMPERIAL BEDROOM - PRODUCTION NOTES

AIR studios, founded by The Beatles’ producer George Martin, opened in 1970 as a four studio complex on the fourth floor of 214 Oxford Street, London, and quickly established itself as one of the finest recording facilities in the world.

Geoff Emerick, a long-time associate of Martin’s, took on production duties for Imperial Bedroom while simultaneously engineering Paul McCartney’s Tug Of War which was being recorded in another studio along the corridor.

Costello evidently relished the experience because, in his own words, "Imperial Bedroom was the only time I ever used the studio as part of the writing process."

Emerick, conscious that Costello liked to work fast, devised a strategy in which, "My goal was to get Elvis to capture the moment, because I realised when I started to work with him that as long as I had the mic placement right and the EQ and limiters ready to go, it was just all set and away you go."

One significant difference between Emerick and Costello’s former producer, Nick Lowe, was that Geoff liked to have vocals very loud in the mix. "There was a conscious effort to turn all the instruments down and put the voice up," remembered Costello. "It’s like, if you listen to old Walker Brothers or Dusty Springfield records, the backing is compressed and only surges up when the voice stops."

To achieve this effect, Emerick used vintage Fairchild compressors, described by Costello as "his secret weapon to give that dynamic effect that modern solid state just can't achieve."

Emerick was also adept at transforming unplanned studio outbursts into useable album content. The best example is perhaps a linking device between four songs, consisting of Costello screaming wordlessly accompanied by a frantic guitar. "It was really just a spur of the moment thing," Emerick later explained. "One minute I’m sitting behind the mixing console and the next minute I hear Elvis screaming; I guess he was just having a good time and letting off some steam."

Tweet this Fact

ELVIS COSTELLO - IMPERIAL BEDROOM

Costello’s seventh, and arguably greatest, album arrived in 1982 at a point when rock’s former 'angry young man' was taking a fresh look at everything he had achieved so far.

With his first flush of late 70s’ hit singles success having run dry, he’d started to re-evaluate virtually every aspect of his life. As he put it himself, "I had enough sense to say, 'If you don’t look after yourself a bit more, you’re going to be dead. Stop taking drugs, stop drinking so much and behave a bit. You really are turning into a bore about being an artist. It’s not important to anybody and, if you carry on like this, you’re not going to do anybody any good."

After years of working with Nick Lowe as his producer, Costello had gone to Nashville in 1981 and recorded the country-influenced Almost Blue with veteran producer Billy Sherrill. As well as being a dramatic stylistic departure for Costello, that experience enabled him to step outside his normal boundaries.

For one thing, he put down his usual compositional tool, the guitar, and moved to a keyboard. "I had a piano and I sat around and I wrote almost all of Imperial Bedroom on the piano … which I can’t play," he admitted. "My father taught me a little bit when I was seventeen."

Well aware of his pianistic shortcomings, he would show what he had done to Attractions keyboardist Steve Nieve who would then, "interpret them, voice them better ways."

This process was underway during the recording of Almost Blue, so come the winter of 1981, when demos for Imperial Bedroom were recorded with house engineer Howard Massey at Pathway Studios in London, most of the songs were already written.

Costello had also become increasingly aware that his aggressive vocal style had become something of a limiting factor. "I didn’t change the keys," he explained, "but I changed the register on about half the vocals on the record. After we recorded the backing tracks, three or four of the songs ended up being an octave lower than we’d rehearsed them."

Another realisation was that, "I was sacrificing the power of certain songs to this mad pursuit of tempo. Everything had to be delivered forcefully. I don’t know whether it was just a natural process or, literally, cumulative exhaustion of what were very intense years. Man Out of Time is the one time I said, ‘No, stop. Let’s play this at the right tempo.’"

The sessions for Imperial Bedroom took place at AIR Studios in London, over a three-month period, under the watchful eye of producer Geoff Emerick, who had earned his spurs as an engineer on several Beatles’ albums.

"We were trying to capture Elvis's spontaneity, because he's a first-take kind of guy," Emerick has recalled. "We wanted to get back to basics. Elvis is very fast. When we did the first session, there was an onslaught of something like eighteen songs, which we cut in fast takes. It took me quite by surprise. From then on, it was a matter of thinking which ones should we record."

Although a lot of tracks were recorded very quickly, Costello was far from satisfied with what had been achieved. "We recorded all the backing tracks and then the band went home and I stayed in the studio on my own for several weeks recording the vocals. I changed two or three of the songs. I wrote a new song on top of what they thought to be the song, and overlaid a new melody and lyric on their original changes."

Where once Costello had relished the minimalist thrills of working strictly in a small band format, he was now forging ahead into other areas, and found Steve Nieve invaluable as an arranger who could realise his grander visions. "Steve didn't want the standard orchestration - first and second violins, cellos and so on," remembered Emerick. "On Town Cryer, and some of the other songs, we used, I think, eighteen violas, which was really unique."

Costello has admitted that, carried away by the excitement of his new direction, "We hired an orchestra for Steve to arrange for. We hired a harpsichord; we had no idea what to do with it. We bought an accordion, and none of us could play it, so it took three of us to wrestle it into submission."

The accordion is heard on The Long Honeymoon, and Elvis clarified the wrestling technique in the sleeve notes to the 2002 album re-issue, explaining how, "Laying the instrument on the table, Steve played the keyboard, while one of us worked the bellows, and a third party held the beast in place."

Not only was Costello exploring new levels of sophistication, he was actively abandoning any attempt at making commercially-marketable music. "We made a record that couldn't possibly get on the radio, and actually relished that," he later revealed. "It was a sort of like, 'Fuck you, we'll just do this now.' Not to the audience, but to the record companies and radio that don't really want you around."

In 1983, Elvis told Paul Rambali of The Face that, "I was making all the production decisions. It's very hard when you're judging your own work. Some of the things that I held out for – when everyone said I was wrong – six months later I found I was wrong! There's that song Kid About It, which I insisted on singing in an entirely unsuitable octave. I was trying to get away from having one vocal feel throughout, the sort of 'one-man-tortured-by-his-art' thing, so I went completely the other way and used overlapping vocals and conflicting styles to suggest there was more than one attitude going on inside the songs. Some of it worked perfectly well, a rather more theatrical way of singing, if you like, because I wanted to get away from that sort of soul singing and do something cooler, in the old-fashioned sense."

Three songs from Imperial Bedroom - Beyond Belief, Man Out of Time and Almost Blue - have remained staples of Costello’s live shows, so it’s worth considering each of those in some detail.

Speaking of the spacious widescreen opening track, Beyond Belief, Costello has explained, "We were moving into the period of big open-spaced music - U2, Echo And The Bunnymen - and suddenly our tight little songs were out of step. This is a ranting kind of song. I was consciously writing words that didn't make sense - to make a blurred picture, because I was living a blurred life."

As the term 'blurred life' suggests, the early 80s were an emotionally troubled time for Costello, not least because his first marriage was disintegrating. As a result many of the album’s lyrics, although rich in clever wordplay, are virtually impenetrable. "Man Out Of Time was the product of a troubling dialogue with myself that continued through my more regretful moments," he has said. "I recall looking at my reflection in the frozen window of a Scandinavian tour bus without any idea who the hell I was supposed to be."

Although he could hide his meanings from his audience in obscure lyrics, the other band members could clearly see what was tearing him up. "Bruce Thomas of The Attractions thought I was being too obsessed with domestic strife. But it wasn’t that I was obsessed with it, it just made the strongest songs. It’s not because of the subject; the saddest songs made the strongest songs. I always write better sad songs."

The third of this trio, Almost Blue, has become Costello’s most-covered song, and was, he has revealed, "written in imitation of the (Lew Brown/Ray Henderson 1931 jazz standard) song The Thrill Is Gone. I had become obsessed with the Chet Baker recording of that tune, firstly the trumpet instrumental and, later, the vocal take. It is probably the most faithful likeness to the model of any of my songs of this time." Costello was understandably delighted when, some years later, he learned that Baker had been including Almost Blue in his live shows.

In a feature of this length, it’s impossible to detail every one of the fifteen tracks on Imperial Bedroom, but Costello’s comments about The Loved Ones are worth repeating for the light they shed on the complexity of his thinking. "That is the hardest song to get over," he said. "Considering it’s got such a light pop tune, it’s like saying, 'Fuck posterity; it’s better to live.' It’s the opposite of Rust Never Sleeps. It’s about, 'Fuck being a junkie and dying in some phony romantic way like Brendan Behan or Dylan Thomas'. Somebody in your family’s got to bury you, you know? That’s a complicated idea to put in a pop song. I didn’t want to write a story around it - I wanted to just throw all of those ideas into a song. Around a good pop hook."

Imperial Bedroom divided reviewers in 1982, but although its reputation has only grown with time, Costello has always been the album’s harshest critic. "In retrospect, I feel some of the songs are just not well written enough," he said in a 1988 interview with Rolling Stone. "Some of them were attempts to create a little mystery room the listener could go into. And in some cases, the subject matter is maybe too large for the song's own good."

Nevertheless, he must harbour considerable affection for it, because he named his most recent tour Imperial Bedroom and Other Chambers. Typically, though, there was no attempt to faithfully reproduce his 1982 classic. "We’re not playing it the way it was originally written or heard," says Costello. "We're going back and listening and saying, 'What's good on those recordings? What isn't so good? What can we do better?"

In an era when most so-called heritage artists are perfectly content to spoon feed their devoted audiences with whatever they find most palatable, we can only be grateful that Elvis Costello remains as unpredictably uncompromising as he has been from the start.

IMPERIAL BEDROOM - PRODUCTION NOTES

AIR studios, founded by The Beatles’ producer George Martin, opened in 1970 as a four studio complex on the fourth floor of 214 Oxford Street, London, and quickly established itself as one of the finest recording facilities in the world.

Geoff Emerick, a long-time associate of Martin’s, took on production duties for Imperial Bedroom while simultaneously engineering Paul McCartney’s Tug Of War which was being recorded in another studio along the corridor.

Costello evidently relished the experience because, in his own words, "Imperial Bedroom was the only time I ever used the studio as part of the writing process."

Emerick, conscious that Costello liked to work fast, devised a strategy in which, "My goal was to get Elvis to capture the moment, because I realised when I started to work with him that as long as I had the mic placement right and the EQ and limiters ready to go, it was just all set and away you go."

One significant difference between Emerick and Costello’s former producer, Nick Lowe, was that Geoff liked to have vocals very loud in the mix. "There was a conscious effort to turn all the instruments down and put the voice up," remembered Costello. "It’s like, if you listen to old Walker Brothers or Dusty Springfield records, the backing is compressed and only surges up when the voice stops."

To achieve this effect, Emerick used vintage Fairchild compressors, described by Costello as "his secret weapon to give that dynamic effect that modern solid state just can't achieve."

Emerick was also adept at transforming unplanned studio outbursts into useable album content. The best example is perhaps a linking device between four songs, consisting of Costello screaming wordlessly accompanied by a frantic guitar. "It was really just a spur of the moment thing," Emerick later explained. "One minute I’m sitting behind the mixing console and the next minute I hear Elvis screaming; I guess he was just having a good time and letting off some steam."