Fact #132299

When:

Short story:

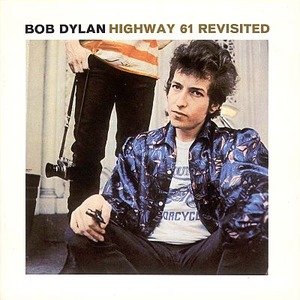

Bob Dylan resumes recording of his sixth album Highway 61 Revisited in Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, USA.

Bob Dylan resumes recording of his sixth album Highway 61 Revisited in Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, USA.Full article:

Bob Johnston (producer) : I heard him, and I wanted to work with him. He was a prophet, and in another few hundred years, they'll realize he stopped the [Vietnam] War. Mercy asked me, "Why do you want to work with him? He's got dirty fingernails and he breaks all the strings on his guitar." But I wanted to.

Before I met him, I had actually seen him in the Village and things like that. He was freaky to me... because I still believe that he's the only prophet we've had since Jesus. I don't think people are gonna realize it for another two or three hundred years when they figure out who really did help stop the Vietnam War, who did change everybody around and why our children aren't hiding under the damn tables now worrying about an atomic war. One day they'll wake up, and they'll realize what they had, instead of asking what kind of album he did and is it as good as the last one. That was always bullshit to me.

What I heard from the people at CBS was that Grossman and Dylan didn't like Tom Wilson, who was producing him. Wilson had come in when John Hammond found Dylan, and they said they didn't like him.

I was afraid they'd give him to Terry Melcher, so I had a meeting with John Hammond, Mercy (Columbia producer/arranger Bob Mercy) and Bill Gallagher (Columbia Records president), and they said, "Okay, you do him."

Someone once asked Dylan how he met me and he said, "I don't know. One night, Wilson was there and the next night Johnston was there."

It was in the Columbia Studios on West 52nd Street. I just walked up to him and said, "Hi, I'm Bob Johnston," and he just smiled and said, "Hi, I'm Bob, too." As for producing, I always say I'm someone who just lets the tapes roll, but anyone who can't write songs, can't sing, can't produce, can't perform really shouldn't be working with an artist. You need to relate on their level, if for no other reason than you can stay out of their way when you need to. All of the other staff producers at Columbia were tapping their feet out of time and whistling out of tune and picking songs based on what their boss liked last week so they could keep their jobs three more months. But I figured Dylan knew something none of us knew, and I wanted to let him get it out. Also, I should tell you that though Like a Rolling Stone was on Highway 61, it was produced by Tom Wilson. I produced all the rest of the songs on it.

The old studios on 52nd Street were a big complex with tons of staff engineers. I walked in on the first day, and there was a German engineer in the studio waiting for me, and he said, "Vot are ve vorking on today?" I told him it was Bob Dylan, and he said, "Do ve haff to?" And I said, "Hell, no," and got another engineer.

I don't know how Tom Wilson recorded him, but when I did Dylan, we set up all of the musicians in the same room, with Bob behind a glass baffle so you could see him. With Dylan, you always had to keep your eye on him. He came in and played a song to the band once and that was how they learned it. He never counted off, just launched right into it, so you always had to keep the tape rolling. And that wasn't easy at Columbia; we were using 4-track for that record, 8-track on Blonde on Blonde, and the machines were way down the hall.

We had union engineers, so one would be in the control room at the console with me, and I'd say, "Roll tape," and he'd tell his assistant near the door, "Roll tape," and he'd yell down the hall to a guy at the other end, "Roll tape," and then they'd start all over again yelling, "Is tape rolling?" God, it took twenty minutes to get those damned machines going. It was like a Three Stooges short.

So I got in the habit of using several machines with Dylan so as not to lose anything. He would start a song on the piano, and if the musicians dropped out during it, he'd go to the guitar and start playing another one. I lost one song that way and said never again, so I always used multiple machines.

I always used three microphones on Dylan, 'cause his head spun around so much. I used a big [Neumann] U47 on him, same as I used on Johnny Cash later. I would put a baffle over the top of his guitar because he played while he sang lead vocals. I didn't use any EQ on the band, just set the mics up right to make each instrument sound the best it could. I used some EQ on Dylan's voice.

I never cared what he did and I never cared what he did in the studio. I was trying to get down anything he was doing next, so we could have a record of it, so the people could hear it all over the world. I figured that was my job.

My job wasn't to be a hero and to tell Paul Simon or Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash or Willie Nelson what the f@#k to do! I thought if you want to be a hero or if you want to take credit, get some other people to work with. Don't work with these people. I wasn't like some other people who were looking to be the next Phil Spector. I had three sons; all I cared about was seeing that it was gonna be a better world. And I think these people made a better world for us.

Harvey Brooks (bassist) : I opened the door to the control room, took a deep breath and entered.

The first person I saw was Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager. Grossman had long gray hair tied in a ponytail and wore round, tinted wire-rimmed glasses. I thought he looked like Benjamin Franklin. A thin, frizzy-haired guy dressed in jeans and boots was standing in the front of the mixing console listening to a playback of “Like a Rolling Stone.” I assumed it was Bob Dylan, though I didn’t know him or what he looked like at the time.

When the music stopped, Grossman asked, who’re you? I told him who, what and why. Dylan quietly muttered “Hi” and went back to listening. Al Kooper then came in to make the official introduction. It was all very cryptic and brief.

I walked into the studio, opened up my case, took out my Fender bass and started to tune. My instrument was strung with La Bella flat wounds, which I still use. I plugged in the Ampeg B-15 amplifier, which was provided by the studio. It sounded warm and percussive. The B-15 was my gig amp as well. Now I use Hartke amplifiers exclusively.

Though I was only 21-years-old, I had already played many club gigs with a range of different performers. I had worked with varying styles and felt I could adapt to about anything on the fly. For that reason, I was comfortable in the studio and was ready for anything Dylan could throw my way.

Suddenly, the studio door burst open and in stormed Michael Bloomfield, a moving ball of pure energy. He wore penny loafers, jeans, a white shirt with rolled-up sleeves and had a Fender Telecaster hanging over his shoulder. Bloomfield’s hair was as electric as his smile. It was the first time I had met or even heard of him.

The other players on the session were Bobby Gregg on drums, Paul Griffin and Frank Owens on piano and Al, who on the “Like a Rolling Stone” recording session two weeks earlier, had nailed his position on organ

At the first session, Joe Macho Jr. had played bass. He had been replaced by Russ Savakus who Dylan didn’t like either. Dylan wanted someone new for the rest of the sessions. Kooper recommended me to Dylan. What Dylan needed was to be comfortable with his bass player. Kooper knew I had a good feel and adapted quickly to any situation.

For Dylan, it was not enough to be a skilled studio musician. He wanted musicians who could adapt quickly to his style. In talking to Bob, I admitted that I hadn’t heard any of his music before the session, but was really impressed by “Like a Rolling Stone,” which I first heard when I walked into the studio.

“Well, these are a little different,” Bob responded. I assumed he meant from his past work, but Bob was bit vague. He gave me a kind of crooked smile and then lit up a cigarette.

Tom Wilson, who had produced Like a Rolling Stone a couple of weeks earlier, also was replaced for unknown reasons. The new producer was Bob Johnston, a Columbia staff producer from Nashville who was already producing Patti Page when he got the Dylan assignment.

Johnston had a “documentary” approach to producing that allowed him to capture fleeting moments in the studio. He was frustrated by the technical bureaucracy at the Columbia studio and ordered several tape machines brought into the control room so he could keep one running at all times in order to capture anything Dylan might want to keep. That tactic worked quite well for an artist like Dylan.

Though the first session for Highway 61 Revisited had been only about two weeks earlier, a lot had happened in the interim. Like a Rolling Stone, recorded at the first session, had been released and caught on like fire.

Only four days earlier, Dylan had been booed by the crowd when he had gone electric at the Newport Folk Festival. It was a pivotal time in his career. He was beginning the transition from being a “pure” folk artist to a rock and roll performer.

Now we were at the second session, my first, uncertain of what was on Dylan’s mind. In a few minutes, he came out of the control room and started to sing the first of three songs we would work on that day. Johnston had set up three-sided baffles, leaving the side that faced the band open so we could see him.

Dylan sang the first song, Tombstone Blues, a few times. There were no chord charts for anyone. It was all done by ear. As a habit, I made a few quick chord charts for myself as I listened to him perform the song. Everyone focused on Dylan, watching for every nuance. Then, the band went for it.

As we began recording, Dylan was still working on the lyrics. He was constantly editing as we were recording. I thought that was a really amazing way that he worked. His guitar or piano part was the guiding element through each song. Every musician in that room was glued to him. We would play until Dylan felt something was right. His poker face never revealed what he was thinking.

It might have taken a couple of takes for everyone to lock in. There were mistakes, of course, but they didn’t matter to Dylan. If the feel was there and the performance was successful, that’s all that mattered. In real life, that’s the way it is. If the overall performance happens, there is always something there. Bob would go into the control room and listen. Bob Johnston may have been the producer keeping the tape rolling, but it was all Dylan deciding what felt right and what didn’t.

Michael Bloomfield’s fiery guitar parts accented Dylan’s phrasing. He was a very explosive guitar player and didn’t settle back into things. He was aggressive and a little bit in front of it. My goal is finding a part that makes the groove happen. Dylan set the feel and direction with his rhythm and my bass parts reflected what I got from him.

Most of my early playing experience had been in R&B bands that performed Wilson Pickett and Jackie Wilson, or tunes by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Playing with Dylan created a totally new category. I call it “jump in and go for it.”

Next, we recorded It Takes a Lot to Laugh and Positively 4th Street the same way. Masters for the three songs were successfully recorded on July 29. Tombstone Blues and It Takes a Lot to Laugh were included on the final Highway 61 Revisited album, but Positively 4th Street was issued as a single-only release.

At the close of the session that first night, Dylan attempted to record Desolation Row, accompanied only by Al on electric guitar and me on bass. There was no drummer, as Bobby Gregg had already gone home. This electric version was eventually released in 2005, on The Bootleg Series Vol. 7 album.

Our producer had a love of and even a bias toward Nashville musicians. It became an underlying topic during the entire session about how good they were. He kept talking about how cool Nashville is. With his comments, I felt it was disparaging to us. I felt Johnston thought of us as New York bumpkins in a way.

This Nashville bias played into Desolation Row. I thought the version without drums that I did with Al that night was slower and definitely more soulful. We really liked it. Clearly, Johnston thought otherwise. On August 2, five more takes were done on Desolation Row. However, the version of the song ultimately used on the album was recorded at an overdub session on August 4.

This time, Johnston’s personal friend, Nashville guitarist Charlie McCoy, who was visiting New York City at the time, was invited to contribute an improvised acoustic guitar part. Russ Savakus played upright bass. We were gone by the time the final take was recorded.

When I left the studio after the final session, I didn’t have a sense of whether or not we had created a hit record. I did know, however, that all the songs felt good. They felt solid. I now understand that’s why Highway 61 Revisited was a successful record. Bob got it. In all the takes he chose, he made sure he got what he wanted from each song.

(Source : blog piece by Harvey Brooks in The Times Of Israel, July 28, 2015)

Tweet this Fact

Before I met him, I had actually seen him in the Village and things like that. He was freaky to me... because I still believe that he's the only prophet we've had since Jesus. I don't think people are gonna realize it for another two or three hundred years when they figure out who really did help stop the Vietnam War, who did change everybody around and why our children aren't hiding under the damn tables now worrying about an atomic war. One day they'll wake up, and they'll realize what they had, instead of asking what kind of album he did and is it as good as the last one. That was always bullshit to me.

What I heard from the people at CBS was that Grossman and Dylan didn't like Tom Wilson, who was producing him. Wilson had come in when John Hammond found Dylan, and they said they didn't like him.

I was afraid they'd give him to Terry Melcher, so I had a meeting with John Hammond, Mercy (Columbia producer/arranger Bob Mercy) and Bill Gallagher (Columbia Records president), and they said, "Okay, you do him."

Someone once asked Dylan how he met me and he said, "I don't know. One night, Wilson was there and the next night Johnston was there."

It was in the Columbia Studios on West 52nd Street. I just walked up to him and said, "Hi, I'm Bob Johnston," and he just smiled and said, "Hi, I'm Bob, too." As for producing, I always say I'm someone who just lets the tapes roll, but anyone who can't write songs, can't sing, can't produce, can't perform really shouldn't be working with an artist. You need to relate on their level, if for no other reason than you can stay out of their way when you need to. All of the other staff producers at Columbia were tapping their feet out of time and whistling out of tune and picking songs based on what their boss liked last week so they could keep their jobs three more months. But I figured Dylan knew something none of us knew, and I wanted to let him get it out. Also, I should tell you that though Like a Rolling Stone was on Highway 61, it was produced by Tom Wilson. I produced all the rest of the songs on it.

The old studios on 52nd Street were a big complex with tons of staff engineers. I walked in on the first day, and there was a German engineer in the studio waiting for me, and he said, "Vot are ve vorking on today?" I told him it was Bob Dylan, and he said, "Do ve haff to?" And I said, "Hell, no," and got another engineer.

I don't know how Tom Wilson recorded him, but when I did Dylan, we set up all of the musicians in the same room, with Bob behind a glass baffle so you could see him. With Dylan, you always had to keep your eye on him. He came in and played a song to the band once and that was how they learned it. He never counted off, just launched right into it, so you always had to keep the tape rolling. And that wasn't easy at Columbia; we were using 4-track for that record, 8-track on Blonde on Blonde, and the machines were way down the hall.

We had union engineers, so one would be in the control room at the console with me, and I'd say, "Roll tape," and he'd tell his assistant near the door, "Roll tape," and he'd yell down the hall to a guy at the other end, "Roll tape," and then they'd start all over again yelling, "Is tape rolling?" God, it took twenty minutes to get those damned machines going. It was like a Three Stooges short.

So I got in the habit of using several machines with Dylan so as not to lose anything. He would start a song on the piano, and if the musicians dropped out during it, he'd go to the guitar and start playing another one. I lost one song that way and said never again, so I always used multiple machines.

I always used three microphones on Dylan, 'cause his head spun around so much. I used a big [Neumann] U47 on him, same as I used on Johnny Cash later. I would put a baffle over the top of his guitar because he played while he sang lead vocals. I didn't use any EQ on the band, just set the mics up right to make each instrument sound the best it could. I used some EQ on Dylan's voice.

I never cared what he did and I never cared what he did in the studio. I was trying to get down anything he was doing next, so we could have a record of it, so the people could hear it all over the world. I figured that was my job.

My job wasn't to be a hero and to tell Paul Simon or Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash or Willie Nelson what the f@#k to do! I thought if you want to be a hero or if you want to take credit, get some other people to work with. Don't work with these people. I wasn't like some other people who were looking to be the next Phil Spector. I had three sons; all I cared about was seeing that it was gonna be a better world. And I think these people made a better world for us.

Harvey Brooks (bassist) : I opened the door to the control room, took a deep breath and entered.

The first person I saw was Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager. Grossman had long gray hair tied in a ponytail and wore round, tinted wire-rimmed glasses. I thought he looked like Benjamin Franklin. A thin, frizzy-haired guy dressed in jeans and boots was standing in the front of the mixing console listening to a playback of “Like a Rolling Stone.” I assumed it was Bob Dylan, though I didn’t know him or what he looked like at the time.

When the music stopped, Grossman asked, who’re you? I told him who, what and why. Dylan quietly muttered “Hi” and went back to listening. Al Kooper then came in to make the official introduction. It was all very cryptic and brief.

I walked into the studio, opened up my case, took out my Fender bass and started to tune. My instrument was strung with La Bella flat wounds, which I still use. I plugged in the Ampeg B-15 amplifier, which was provided by the studio. It sounded warm and percussive. The B-15 was my gig amp as well. Now I use Hartke amplifiers exclusively.

Though I was only 21-years-old, I had already played many club gigs with a range of different performers. I had worked with varying styles and felt I could adapt to about anything on the fly. For that reason, I was comfortable in the studio and was ready for anything Dylan could throw my way.

Suddenly, the studio door burst open and in stormed Michael Bloomfield, a moving ball of pure energy. He wore penny loafers, jeans, a white shirt with rolled-up sleeves and had a Fender Telecaster hanging over his shoulder. Bloomfield’s hair was as electric as his smile. It was the first time I had met or even heard of him.

The other players on the session were Bobby Gregg on drums, Paul Griffin and Frank Owens on piano and Al, who on the “Like a Rolling Stone” recording session two weeks earlier, had nailed his position on organ

At the first session, Joe Macho Jr. had played bass. He had been replaced by Russ Savakus who Dylan didn’t like either. Dylan wanted someone new for the rest of the sessions. Kooper recommended me to Dylan. What Dylan needed was to be comfortable with his bass player. Kooper knew I had a good feel and adapted quickly to any situation.

For Dylan, it was not enough to be a skilled studio musician. He wanted musicians who could adapt quickly to his style. In talking to Bob, I admitted that I hadn’t heard any of his music before the session, but was really impressed by “Like a Rolling Stone,” which I first heard when I walked into the studio.

“Well, these are a little different,” Bob responded. I assumed he meant from his past work, but Bob was bit vague. He gave me a kind of crooked smile and then lit up a cigarette.

Tom Wilson, who had produced Like a Rolling Stone a couple of weeks earlier, also was replaced for unknown reasons. The new producer was Bob Johnston, a Columbia staff producer from Nashville who was already producing Patti Page when he got the Dylan assignment.

Johnston had a “documentary” approach to producing that allowed him to capture fleeting moments in the studio. He was frustrated by the technical bureaucracy at the Columbia studio and ordered several tape machines brought into the control room so he could keep one running at all times in order to capture anything Dylan might want to keep. That tactic worked quite well for an artist like Dylan.

Though the first session for Highway 61 Revisited had been only about two weeks earlier, a lot had happened in the interim. Like a Rolling Stone, recorded at the first session, had been released and caught on like fire.

Only four days earlier, Dylan had been booed by the crowd when he had gone electric at the Newport Folk Festival. It was a pivotal time in his career. He was beginning the transition from being a “pure” folk artist to a rock and roll performer.

Now we were at the second session, my first, uncertain of what was on Dylan’s mind. In a few minutes, he came out of the control room and started to sing the first of three songs we would work on that day. Johnston had set up three-sided baffles, leaving the side that faced the band open so we could see him.

Dylan sang the first song, Tombstone Blues, a few times. There were no chord charts for anyone. It was all done by ear. As a habit, I made a few quick chord charts for myself as I listened to him perform the song. Everyone focused on Dylan, watching for every nuance. Then, the band went for it.

As we began recording, Dylan was still working on the lyrics. He was constantly editing as we were recording. I thought that was a really amazing way that he worked. His guitar or piano part was the guiding element through each song. Every musician in that room was glued to him. We would play until Dylan felt something was right. His poker face never revealed what he was thinking.

It might have taken a couple of takes for everyone to lock in. There were mistakes, of course, but they didn’t matter to Dylan. If the feel was there and the performance was successful, that’s all that mattered. In real life, that’s the way it is. If the overall performance happens, there is always something there. Bob would go into the control room and listen. Bob Johnston may have been the producer keeping the tape rolling, but it was all Dylan deciding what felt right and what didn’t.

Michael Bloomfield’s fiery guitar parts accented Dylan’s phrasing. He was a very explosive guitar player and didn’t settle back into things. He was aggressive and a little bit in front of it. My goal is finding a part that makes the groove happen. Dylan set the feel and direction with his rhythm and my bass parts reflected what I got from him.

Most of my early playing experience had been in R&B bands that performed Wilson Pickett and Jackie Wilson, or tunes by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Playing with Dylan created a totally new category. I call it “jump in and go for it.”

Next, we recorded It Takes a Lot to Laugh and Positively 4th Street the same way. Masters for the three songs were successfully recorded on July 29. Tombstone Blues and It Takes a Lot to Laugh were included on the final Highway 61 Revisited album, but Positively 4th Street was issued as a single-only release.

At the close of the session that first night, Dylan attempted to record Desolation Row, accompanied only by Al on electric guitar and me on bass. There was no drummer, as Bobby Gregg had already gone home. This electric version was eventually released in 2005, on The Bootleg Series Vol. 7 album.

Our producer had a love of and even a bias toward Nashville musicians. It became an underlying topic during the entire session about how good they were. He kept talking about how cool Nashville is. With his comments, I felt it was disparaging to us. I felt Johnston thought of us as New York bumpkins in a way.

This Nashville bias played into Desolation Row. I thought the version without drums that I did with Al that night was slower and definitely more soulful. We really liked it. Clearly, Johnston thought otherwise. On August 2, five more takes were done on Desolation Row. However, the version of the song ultimately used on the album was recorded at an overdub session on August 4.

This time, Johnston’s personal friend, Nashville guitarist Charlie McCoy, who was visiting New York City at the time, was invited to contribute an improvised acoustic guitar part. Russ Savakus played upright bass. We were gone by the time the final take was recorded.

When I left the studio after the final session, I didn’t have a sense of whether or not we had created a hit record. I did know, however, that all the songs felt good. They felt solid. I now understand that’s why Highway 61 Revisited was a successful record. Bob got it. In all the takes he chose, he made sure he got what he wanted from each song.

(Source : blog piece by Harvey Brooks in The Times Of Israel, July 28, 2015)