Fact #127282

When:

Short story:

Full article:

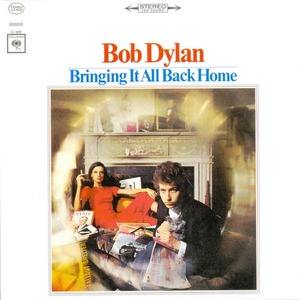

A brand new and enduring musical genre, folk-rock, sprang into being as a direct result of Bob Dylan’s fifth album, Bringing It All Back Home. As with most such revolutionary moments, of course, there was no master plan. It happened because it had to.

With his early acoustic albums, Dylan had revolutionised the early 60s folk scene simply by writing his own songs. Chart-topping albums and singles by The Kingston Trio, The Highwaymen and the Rooftop Singers testify to the massive popularity of folk music at the time, but all of these acts covered traditional songs. The scene generated very little in the way of original material until Dylan came along, at which point the floodgates opened and every sensitive teenager who could pick three chords on a battered acoustic guitar suddenly became a folksy singer-songwriter.

Dylan was also seen as the inventor of protest music (see entry on Freewheelin’), so the eyes of the music community were firmly fixed on him, watching his every move.

However, when he went into Columbia’s New York studios on13 January 1965 to begin recording sessions for Bringing It All Back Home, he was not planning to invent a new electric folk style. One entire side of the album, in fact, remained firmly in his acoustic solo troubadour mode.

There were, however, certain songs which he felt were not going to work without additional instrumentation. “I had this thing called Subterranean Homesick Blues,” he explained later. “It just didn’t sound right by myself.” Maybe that’s because its rapid-fire semi-rapped lyric bears more than a passing resemblance to Chuck Berry’s Too Much Monkey Business – a rock’n’roll classic that Dylan would have known well.

The popular notion that Dylan was a Greenwich Village folkie who made a shocking volte-face into rock’n’roll is one that has long muddied the waters around his next move. Dylan grew up in the 50s listening to rock’n’roll, particularly enjoying Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers and Elvis Presley, of whom he has said, “When I first heard Elvis' voice I just knew that I wasn’t going to work for anybody; and nobody was going to be my boss...”

On 5 June 1959 when he left Hibbing High School, Minnesota, the school yearbook noted that he intended, “to follow Little Richard”, and one of his first paid jobs was a brief stint as pianist in teen idol Bobby Vee’s band.

So his decision to bring in rock players for Subterranean Homesick Blues was more a return to his roots than a radical re-structuring of folk idioms. As a guitarist, Dylan chose Bruce Langhorne, who he’d worked with in 1962, during rarely mentioned unreleased electric sessions for the album Freewheelin’.

Dylan’s producer, Tom Wilson, chose the rest of the band, including John Sebastian, later to form the Lovin’ Spoonful) and John Hammond Jr, who subsequently became a highly-regarded bluesman.

Photographer Daniel Kramer, who attended the sessions, vividly recalls the excitement and elation when Maggie’s Farm was first played back. “There was no question about it – it swung, it was happy, it was good music and, most of all, it was Dylan.”

The rock instrumentation also worked a treat for another uptempo Chuck Berry-ish workout, Outlaw Blues, and for the hilariously surreal On The Road Again. The guitars are also plugged in, but appropriately more mellow for two of Dylan’s most memorable love songs, She Belongs To Me and Love Minus Zero/No Limit

The album gave him his first Top Ten entry, and Subterranean Homesick Blues sneaked into the Top 40 singles chart but, even more significantly, one of the album’s acoustic tracks, Mr Tambourine Man, went to No1 in June in an electrified version by The Byrds. Folk rock had arrived and the overwhelming mass of American teens embraced it immediately, soaking up similarly styled hits from Simon & Garfunkel, The Turtles, Barry McGuire.

Unfortunately, to the folk fraternity who had previously adored him, amplified folk was a sin against nature. When Dylan debuted his new electric band at the Newport Folk Festival on 25 July he was booed off the stage, and similar demonstrations of dismay and anger greeted him wherever he toured for the rest of the year.

He was, nevertheless, not about turn back. Highway 61 Revisited followed just six months after Bringing It All Back Home, and this time the electricity crackled and fizzed from every groove.

Guitarist Mike Bloomfield once claimed that the sessions were chaotic because, “no-one had any idea what the music was supposed to sound like.” Neither Dylan nor producer Tom Wilson, according to Bloomfield, directed the musicians. “It was a matter of pure chance.” More likely it was a matter of choosing the right musicians to start with, then giving them their creative head.

The opening swagger and swirl of Al Kooper’s organ and Paul Griffin’s piano on Like A Rolling Stone left no doubt that in a few short months Dylan had made a quantum leap and was now the king of a hill built by his own hand. Snarling and sneering his way through the vitriolic lyric, Dylan had never before sounded so confident. (He was certainly confident enough to release it as a six minute single against the advice of Columbia Records who insisted that radio wouldn’t play anything over three minutes in length. It went top 5 on both sides of the Atlantic.)

Bloomfield’s stinging lead guitar kicks Tombstone Blues into a higher rock’n’roll gear than Dylan had previously managed, but the album’s real strength is not its style but its content. Songs like It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry and Ballad Of A Thin Man, are beautifully understated, with every instrument perfectly complementing Dylan’s straggling melodies.

The lyrics too had leapt ahead, with virtually every line of Desolation Row elegantly conjuring word pictures that combine into a dark and surreal movie playing in the back of the listener’s head.

Arguably, Highway 61 Revisited also marks the dividing line between rock’n’roll and rock. Here was a music too cerebral to be pop, too bluesy and ballsy to be folk-rock and, most significantly, it was also too sophisticated to be rock’n’roll.

Even forty years after its release, this is a hard album to fault. The worst that can be said is that it stands responsible for countless crimes against songwriting committed by legions of inferior artists who misguidedly imagined themselves to be the next Bob Dylan.

(Source : by Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums from Backbeat Press, 2007)

Tweet this Fact

With his early acoustic albums, Dylan had revolutionised the early 60s folk scene simply by writing his own songs. Chart-topping albums and singles by The Kingston Trio, The Highwaymen and the Rooftop Singers testify to the massive popularity of folk music at the time, but all of these acts covered traditional songs. The scene generated very little in the way of original material until Dylan came along, at which point the floodgates opened and every sensitive teenager who could pick three chords on a battered acoustic guitar suddenly became a folksy singer-songwriter.

Dylan was also seen as the inventor of protest music (see entry on Freewheelin’), so the eyes of the music community were firmly fixed on him, watching his every move.

However, when he went into Columbia’s New York studios on13 January 1965 to begin recording sessions for Bringing It All Back Home, he was not planning to invent a new electric folk style. One entire side of the album, in fact, remained firmly in his acoustic solo troubadour mode.

There were, however, certain songs which he felt were not going to work without additional instrumentation. “I had this thing called Subterranean Homesick Blues,” he explained later. “It just didn’t sound right by myself.” Maybe that’s because its rapid-fire semi-rapped lyric bears more than a passing resemblance to Chuck Berry’s Too Much Monkey Business – a rock’n’roll classic that Dylan would have known well.

The popular notion that Dylan was a Greenwich Village folkie who made a shocking volte-face into rock’n’roll is one that has long muddied the waters around his next move. Dylan grew up in the 50s listening to rock’n’roll, particularly enjoying Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers and Elvis Presley, of whom he has said, “When I first heard Elvis' voice I just knew that I wasn’t going to work for anybody; and nobody was going to be my boss...”

On 5 June 1959 when he left Hibbing High School, Minnesota, the school yearbook noted that he intended, “to follow Little Richard”, and one of his first paid jobs was a brief stint as pianist in teen idol Bobby Vee’s band.

So his decision to bring in rock players for Subterranean Homesick Blues was more a return to his roots than a radical re-structuring of folk idioms. As a guitarist, Dylan chose Bruce Langhorne, who he’d worked with in 1962, during rarely mentioned unreleased electric sessions for the album Freewheelin’.

Dylan’s producer, Tom Wilson, chose the rest of the band, including John Sebastian, later to form the Lovin’ Spoonful) and John Hammond Jr, who subsequently became a highly-regarded bluesman.

Photographer Daniel Kramer, who attended the sessions, vividly recalls the excitement and elation when Maggie’s Farm was first played back. “There was no question about it – it swung, it was happy, it was good music and, most of all, it was Dylan.”

The rock instrumentation also worked a treat for another uptempo Chuck Berry-ish workout, Outlaw Blues, and for the hilariously surreal On The Road Again. The guitars are also plugged in, but appropriately more mellow for two of Dylan’s most memorable love songs, She Belongs To Me and Love Minus Zero/No Limit

The album gave him his first Top Ten entry, and Subterranean Homesick Blues sneaked into the Top 40 singles chart but, even more significantly, one of the album’s acoustic tracks, Mr Tambourine Man, went to No1 in June in an electrified version by The Byrds. Folk rock had arrived and the overwhelming mass of American teens embraced it immediately, soaking up similarly styled hits from Simon & Garfunkel, The Turtles, Barry McGuire.

Unfortunately, to the folk fraternity who had previously adored him, amplified folk was a sin against nature. When Dylan debuted his new electric band at the Newport Folk Festival on 25 July he was booed off the stage, and similar demonstrations of dismay and anger greeted him wherever he toured for the rest of the year.

He was, nevertheless, not about turn back. Highway 61 Revisited followed just six months after Bringing It All Back Home, and this time the electricity crackled and fizzed from every groove.

Guitarist Mike Bloomfield once claimed that the sessions were chaotic because, “no-one had any idea what the music was supposed to sound like.” Neither Dylan nor producer Tom Wilson, according to Bloomfield, directed the musicians. “It was a matter of pure chance.” More likely it was a matter of choosing the right musicians to start with, then giving them their creative head.

The opening swagger and swirl of Al Kooper’s organ and Paul Griffin’s piano on Like A Rolling Stone left no doubt that in a few short months Dylan had made a quantum leap and was now the king of a hill built by his own hand. Snarling and sneering his way through the vitriolic lyric, Dylan had never before sounded so confident. (He was certainly confident enough to release it as a six minute single against the advice of Columbia Records who insisted that radio wouldn’t play anything over three minutes in length. It went top 5 on both sides of the Atlantic.)

Bloomfield’s stinging lead guitar kicks Tombstone Blues into a higher rock’n’roll gear than Dylan had previously managed, but the album’s real strength is not its style but its content. Songs like It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry and Ballad Of A Thin Man, are beautifully understated, with every instrument perfectly complementing Dylan’s straggling melodies.

The lyrics too had leapt ahead, with virtually every line of Desolation Row elegantly conjuring word pictures that combine into a dark and surreal movie playing in the back of the listener’s head.

Arguably, Highway 61 Revisited also marks the dividing line between rock’n’roll and rock. Here was a music too cerebral to be pop, too bluesy and ballsy to be folk-rock and, most significantly, it was also too sophisticated to be rock’n’roll.

Even forty years after its release, this is a hard album to fault. The worst that can be said is that it stands responsible for countless crimes against songwriting committed by legions of inferior artists who misguidedly imagined themselves to be the next Bob Dylan.

(Source : by Johnny Black, first published in the book Albums from Backbeat Press, 2007)