Fact #121201

When:

Short story:

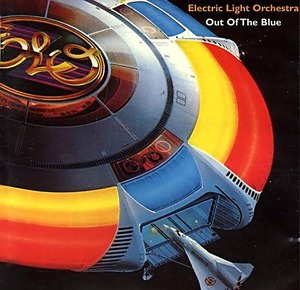

The Electric Light Orchestra (aka ELO), begin recording the LP Out Of The Blue at Musicland Studios, Arabella House, Munich, Germany, Europe.

The Electric Light Orchestra (aka ELO), begin recording the LP Out Of The Blue at Musicland Studios, Arabella House, Munich, Germany, Europe.Full article:

Jeff Lynne : The boss of United Artists asked me if I would do a double live album, because Peter Frampton had just had a huge hit with his one [Frampton Comes Alive!]. I said, “Oh, I wish you’d said studio album. I’d have done that, but I don’t want to do a live album.” Later on he came back to me and said, “OK, you’re on. Studio album!” It was terrific that I got the freedom to do it.

I wrote most of the album very quickly in a little chalet in Switzerland, where I’d gone with all my gear – electric piano, bass, guitar. I was there for two weeks and didn’t come up with anything. Best go down the pub then! Actually I was getting worried because I’d done nothing in a fortnight and I only had a month to write the tunes, but finally they started coming to me.

One of the first ones was Mr Blue Sky. It had been cloudy and misty and horrible, you couldn’t see where you were, and then one day the sun came out and the mist disappeared. It was fantastic, these giant mountains appeared everywhere. So I wrote Mr Blue Sky – very literal!

The whole Concerto For A Rainy Day kind of came out of that. I loved the second side of Abbey Road and I thought I wouldn’t mind trying a suite like that. Because it was a double album I had so much room to work with. It was quite complex to make.

(Source : Uncut, 2014)

Reinhold Mack (engineer, Musicland Studios) : Every morning, his (Jeff Lynne's) attitude would be cold, as if I'd never met him before; walking straight past me without even saying hello, whereas at night, after about twelve pints of beer, he'd be sitting on my lap, kissing me good night. In between, he'd leave the engineering completely to me and ask things like, 'Can you get a big piano sound?' After I tried my best to do that, he'd then say, 'OK, that's really good. Now can you screw it up?' 'What's the point of doing this?' I'd ask. 'I could have screwed it up in the first place.'

We had close to a love/hate working relationship. In fact, if you ask him he'll still tell you that the most annoying thing about me was when he'd ask me to do something and I would reply, 'For what purpose?' Not the most diplomatic approach, I know. Jeff loved having the total freedom of doing weird things, putting mics in strange places, hearing unusual sounds, then changing his mind and doing something completely different. However, he'd never explain his ideas, and until he began overdubbing his vocal onto a song's rhythm track, I'd have no clue about how the melody would go or where the singing would be. This made it hard to foresee if the sounds we were creating were in the right place.

Jeff asking me, 'Can you make the song sound weird?' or 'Can you make it sound more weird?' was about as specific as he would get. Sometimes I'd ask him what 'weird' meant, and another of his standard comments was 'You said you could do it when you were retained for the job.' There was always way too much stuff on everything, and after Jeff kept adding and adding and adding, I'd be thinking, 'How in hell am I going to mix that?' It was a challenge to make sure the various elements could be heard. The mixes were extremely convoluted, and it therefore came down to a choice of what should be featured at which point. Then again, if I was struggling with something, Jeff would just say, 'Never you mind, you won't hear any of that'.

During the (A New World Record) sessions, we had installed a new Harrison console. We now had Westlake monitors, and during a meeting with Paul Ford, Glenn Phoenix and Tom Hidley I said I'd like to have a console on which I could push a button to play the six two-track machines, two four-tracks, two 16-tracks and two 24-tracks. Monitoring would be in there — I didn't want to do any patching — and everything would be switchable for different configurations. Tom said, 'I might just have the console for you,' and he hooked me up with Dave Harrison.

The Harrison had a matrix in each channel, with diodes enabling the switching. The faders were VCAs, you could flip the whole thing so that the path was from the preamp, you could have EQ in or out, you could monitor two four-track machines, and you could pretty much do anything at the push of a couple of buttons. It had a very clean recording sound. You'd go from the preamp over the monitor port onto the tape machine, and that was it; a really short and clean signal path.

The console arrived in the middle of the sessions for A New World Record and I initially managed to wire up the first 16 channels so we could at least record through it that same night, while I told Jeff, 'We can't really hear things too well'. An assistant and I were soldering away until the early hours of the morning, and I wired up more channels as we went along and recorded the backing tracks. Until then, Jeff would go back to England to record the strings, but after we had the Harrison up and running, the strings were recorded at Musicland with members of the Munich Symphony Orchestra.

(Source : Sound On Sound, interview by Ri chard Buskin, September 2013)

Jeff Lynne : I was trying out new things, like the Vocoder, which I used on Mr Blue Sky. The factory that had just built the prototype was in Stuttgart, which was only an hour from Munich. Talk about luck! So we sent the girlfriends off to pick it up. There was no manual, it was that new. We spent the whole day just getting it to do something, but once we got it going it was beautiful. It’s still the best Vocoder I’ve heard. That was a treat, you always want to innovate and get ahead with technology.

(Source : Uncut, 2014)

Jeff Lynne : It (Mr. Blue Sky) captured all what ELO, my vision of ELO, was all about. All the bits that come in and out, the backing vocals, the cellos sliding, all the little naughty bits, the sound effects, everything is exactly what I imagined ELO to be.

(Source : not known)

Reinhold Mack : I told Jeff, 'If you want to record the strings here in Munich, the people from the Munich Symphony Orchestra will charge you either by the hour or for the session, and there will be no demands like in England for tea breaks, union fees and exactly how long the sessions will be. That way, he could tell the musicians precisely what he wanted them to play or what he wanted them to redo and nobody would complain.

Before Out Of The Blue, Jeff already had a winning formula. Still, despite the saying 'Don't change horses in midstream', I thought we could do things bigger and better, so I suggested recording the strings on a huge sound stage at Munich's Bavaria Film studio. We got a 54-piece string section in there, but it was a complete disaster. I could not get the right sound to save my life. In the orchestral sense, it was fine, but it wasn't tight enough and I therefore had to tell all those guys, 'Look, it just isn't working. Can you go over to Musicland? We don't have enough chairs, headphones or music stands there, so whoever wants to come should please bring a chair, a pair of headphones and a music stand.'

Some of those classically trained musicians, feeling like they were back in kindergarten, clearly weren't going to stand for this, but about 80 percent of them said, 'Sure, see you there in an hour,' and they all turned up. As there was also a 32-piece choir, it had to perform in the lobby while some of the orchestra musicians played their instruments lined up against the walls. The place was mobbed, and in those circumstances the sound we got on tracks like 'Mr Blue Sky' was pretty good.”

(Source : Sound On Sound, interview by Ri chard Buskin, September 2013)

Jeff Lynne : It (Sweet Talkin' Woman) was originally a song called Dead End Street. I'd done all the words and everything, finished it. And I came down the next day in the studio and I went, 'I hate that. Let's rub all the vocals off.' And so, he goes, 'Really?' Y'know, me engineer. And I said, 'Yup. Get rid off everything off there. Whatever to do with the vocals.' And he did. He rubbed 'em all off. And I'd been sitting up in the hotel, which is above the studio, working at night just trying to think of a new tune and new words, which I did. And tried it the next day and there they worked. So, it was a good job I did, but it also meant changing the arrangement slightly. So a lot of pairs of scissors were used that day."

(Source : interview with Uncle Joe Benson on Off the Record)

Jeff Lynne : It only took 3 months to make a double album in 1977 - now it takes years. Out of the Blue was probably the hardest work I've ever done but also the most satisfying. It was a time of total music for me, and once I'd got rolling, the songs just kept on coming. Total music and probably most of the beer gardens in Munich, (just by way of a distraction)." (Source : interview in 2006)

Touring the album was impossible, though, a proper pain in the arse, and I started to get fed up with all the strings: “Argh, fuckin’ hell, not another string session today…” It became a bit of a formula. I made a lot of electronic records after Out Of The Blue.

(Source : Uncut, 2014)

Jeff Lynne : There was no way of following that (Out Of The Blue), but there were contracts to fulfil, so I was forced to do things I didn’t want to do, just because of signing bits of paper when you don’t know what you’re doing: Sign that? Oh yeah, of course, thank yo There was no way of following that, but there were contracts to fulfil, so I was forced to do things I didn’t want to do, just because of signing bits of paper when you don’t know what you’re doing: Sign that? Oh yeah, of course, thank you! You can have 50 quid and all the brown ale you can drink. You don’t realise what you’re getting into. So it turned out I had to do another 93 albums for ELO!

(Source : not known)

ADDITIONAL THOUGHTS ON MUSICLAND STUDIOS....

Brian May (Queen) : It was a real strange place... Zeppelin did a lot of recording down there, as did Deep Purple... but it was an utterly depressing place... and people used to commit suicide by jumping off the top of that building quite frequently.

They have this thing in Munich called The Fohn (wind) and when The Fohn blows... people go nuts and they commit suicide. It's a studio down in the depths of this huge high-rise building... with no windows and no contact with the outside world.

(Source : interview in Daily Express, Sep 2, 2012)

Tweet this Fact

I wrote most of the album very quickly in a little chalet in Switzerland, where I’d gone with all my gear – electric piano, bass, guitar. I was there for two weeks and didn’t come up with anything. Best go down the pub then! Actually I was getting worried because I’d done nothing in a fortnight and I only had a month to write the tunes, but finally they started coming to me.

One of the first ones was Mr Blue Sky. It had been cloudy and misty and horrible, you couldn’t see where you were, and then one day the sun came out and the mist disappeared. It was fantastic, these giant mountains appeared everywhere. So I wrote Mr Blue Sky – very literal!

The whole Concerto For A Rainy Day kind of came out of that. I loved the second side of Abbey Road and I thought I wouldn’t mind trying a suite like that. Because it was a double album I had so much room to work with. It was quite complex to make.

(Source : Uncut, 2014)

Reinhold Mack (engineer, Musicland Studios) : Every morning, his (Jeff Lynne's) attitude would be cold, as if I'd never met him before; walking straight past me without even saying hello, whereas at night, after about twelve pints of beer, he'd be sitting on my lap, kissing me good night. In between, he'd leave the engineering completely to me and ask things like, 'Can you get a big piano sound?' After I tried my best to do that, he'd then say, 'OK, that's really good. Now can you screw it up?' 'What's the point of doing this?' I'd ask. 'I could have screwed it up in the first place.'

We had close to a love/hate working relationship. In fact, if you ask him he'll still tell you that the most annoying thing about me was when he'd ask me to do something and I would reply, 'For what purpose?' Not the most diplomatic approach, I know. Jeff loved having the total freedom of doing weird things, putting mics in strange places, hearing unusual sounds, then changing his mind and doing something completely different. However, he'd never explain his ideas, and until he began overdubbing his vocal onto a song's rhythm track, I'd have no clue about how the melody would go or where the singing would be. This made it hard to foresee if the sounds we were creating were in the right place.

Jeff asking me, 'Can you make the song sound weird?' or 'Can you make it sound more weird?' was about as specific as he would get. Sometimes I'd ask him what 'weird' meant, and another of his standard comments was 'You said you could do it when you were retained for the job.' There was always way too much stuff on everything, and after Jeff kept adding and adding and adding, I'd be thinking, 'How in hell am I going to mix that?' It was a challenge to make sure the various elements could be heard. The mixes were extremely convoluted, and it therefore came down to a choice of what should be featured at which point. Then again, if I was struggling with something, Jeff would just say, 'Never you mind, you won't hear any of that'.

During the (A New World Record) sessions, we had installed a new Harrison console. We now had Westlake monitors, and during a meeting with Paul Ford, Glenn Phoenix and Tom Hidley I said I'd like to have a console on which I could push a button to play the six two-track machines, two four-tracks, two 16-tracks and two 24-tracks. Monitoring would be in there — I didn't want to do any patching — and everything would be switchable for different configurations. Tom said, 'I might just have the console for you,' and he hooked me up with Dave Harrison.

The Harrison had a matrix in each channel, with diodes enabling the switching. The faders were VCAs, you could flip the whole thing so that the path was from the preamp, you could have EQ in or out, you could monitor two four-track machines, and you could pretty much do anything at the push of a couple of buttons. It had a very clean recording sound. You'd go from the preamp over the monitor port onto the tape machine, and that was it; a really short and clean signal path.

The console arrived in the middle of the sessions for A New World Record and I initially managed to wire up the first 16 channels so we could at least record through it that same night, while I told Jeff, 'We can't really hear things too well'. An assistant and I were soldering away until the early hours of the morning, and I wired up more channels as we went along and recorded the backing tracks. Until then, Jeff would go back to England to record the strings, but after we had the Harrison up and running, the strings were recorded at Musicland with members of the Munich Symphony Orchestra.

(Source : Sound On Sound, interview by Ri chard Buskin, September 2013)

Jeff Lynne : I was trying out new things, like the Vocoder, which I used on Mr Blue Sky. The factory that had just built the prototype was in Stuttgart, which was only an hour from Munich. Talk about luck! So we sent the girlfriends off to pick it up. There was no manual, it was that new. We spent the whole day just getting it to do something, but once we got it going it was beautiful. It’s still the best Vocoder I’ve heard. That was a treat, you always want to innovate and get ahead with technology.

(Source : Uncut, 2014)

Jeff Lynne : It (Mr. Blue Sky) captured all what ELO, my vision of ELO, was all about. All the bits that come in and out, the backing vocals, the cellos sliding, all the little naughty bits, the sound effects, everything is exactly what I imagined ELO to be.

(Source : not known)

Reinhold Mack : I told Jeff, 'If you want to record the strings here in Munich, the people from the Munich Symphony Orchestra will charge you either by the hour or for the session, and there will be no demands like in England for tea breaks, union fees and exactly how long the sessions will be. That way, he could tell the musicians precisely what he wanted them to play or what he wanted them to redo and nobody would complain.

Before Out Of The Blue, Jeff already had a winning formula. Still, despite the saying 'Don't change horses in midstream', I thought we could do things bigger and better, so I suggested recording the strings on a huge sound stage at Munich's Bavaria Film studio. We got a 54-piece string section in there, but it was a complete disaster. I could not get the right sound to save my life. In the orchestral sense, it was fine, but it wasn't tight enough and I therefore had to tell all those guys, 'Look, it just isn't working. Can you go over to Musicland? We don't have enough chairs, headphones or music stands there, so whoever wants to come should please bring a chair, a pair of headphones and a music stand.'

Some of those classically trained musicians, feeling like they were back in kindergarten, clearly weren't going to stand for this, but about 80 percent of them said, 'Sure, see you there in an hour,' and they all turned up. As there was also a 32-piece choir, it had to perform in the lobby while some of the orchestra musicians played their instruments lined up against the walls. The place was mobbed, and in those circumstances the sound we got on tracks like 'Mr Blue Sky' was pretty good.”

(Source : Sound On Sound, interview by Ri chard Buskin, September 2013)

Jeff Lynne : It (Sweet Talkin' Woman) was originally a song called Dead End Street. I'd done all the words and everything, finished it. And I came down the next day in the studio and I went, 'I hate that. Let's rub all the vocals off.' And so, he goes, 'Really?' Y'know, me engineer. And I said, 'Yup. Get rid off everything off there. Whatever to do with the vocals.' And he did. He rubbed 'em all off. And I'd been sitting up in the hotel, which is above the studio, working at night just trying to think of a new tune and new words, which I did. And tried it the next day and there they worked. So, it was a good job I did, but it also meant changing the arrangement slightly. So a lot of pairs of scissors were used that day."

(Source : interview with Uncle Joe Benson on Off the Record)

Jeff Lynne : It only took 3 months to make a double album in 1977 - now it takes years. Out of the Blue was probably the hardest work I've ever done but also the most satisfying. It was a time of total music for me, and once I'd got rolling, the songs just kept on coming. Total music and probably most of the beer gardens in Munich, (just by way of a distraction)." (Source : interview in 2006)

Touring the album was impossible, though, a proper pain in the arse, and I started to get fed up with all the strings: “Argh, fuckin’ hell, not another string session today…” It became a bit of a formula. I made a lot of electronic records after Out Of The Blue.

(Source : Uncut, 2014)

Jeff Lynne : There was no way of following that (Out Of The Blue), but there were contracts to fulfil, so I was forced to do things I didn’t want to do, just because of signing bits of paper when you don’t know what you’re doing: Sign that? Oh yeah, of course, thank yo There was no way of following that, but there were contracts to fulfil, so I was forced to do things I didn’t want to do, just because of signing bits of paper when you don’t know what you’re doing: Sign that? Oh yeah, of course, thank you! You can have 50 quid and all the brown ale you can drink. You don’t realise what you’re getting into. So it turned out I had to do another 93 albums for ELO!

(Source : not known)

ADDITIONAL THOUGHTS ON MUSICLAND STUDIOS....

Brian May (Queen) : It was a real strange place... Zeppelin did a lot of recording down there, as did Deep Purple... but it was an utterly depressing place... and people used to commit suicide by jumping off the top of that building quite frequently.

They have this thing in Munich called The Fohn (wind) and when The Fohn blows... people go nuts and they commit suicide. It's a studio down in the depths of this huge high-rise building... with no windows and no contact with the outside world.

(Source : interview in Daily Express, Sep 2, 2012)